By Peyman Pejman

Few cultures have seen as much disruption, assimilation, and contradiction as the Iranian culture has – and not just in the past few decades. Understanding the dynamics and parameters of cultural change can only help further accommodation and assimilation.

One writer who has contributed greatly to that study is Bahiyyih Nakhjavani. She grew up in Uganda, was educated in the United Kingdom and the United States, and now lives in France. She is the author of four novels and one non-fiction book on fundamentalism. Her novels have been translated into French, Italian, Spanish, German, Dutch, Greek, Turkish, Hebrew, Russian and Korean.

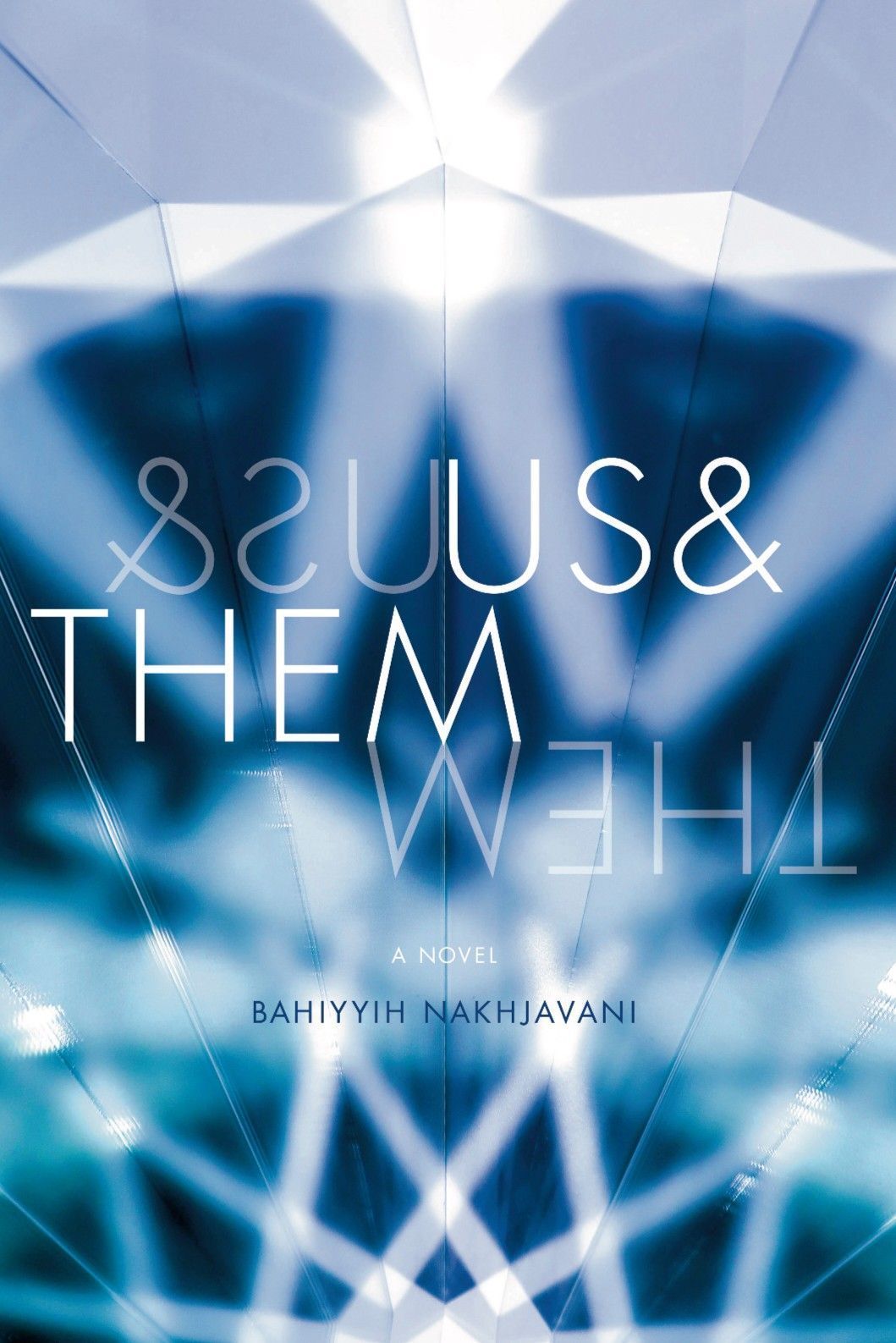

Ms. Nakhjavani spoke to Kayhan Life about her latest novel, “Us & Them.”

Ms. Nakhjavani spoke to Kayhan Life about her latest novel, “Us & Them.”

What is the synopsis of the book?

“Us & Them” is about an elderly Iranian woman, Bibijan, and her two daughters: Goli, who lives in L.A. with her family, and Lili, who is an artist in Paris.

Bibijan’s youngest son, Ali, disappeared in the Iran-Iraq war. She has refused to leave Iran as long as his fate is unknown. Now, she is finally travelling to L.A. for a “surprise” Nowruz party, imagining that he has been found.

Between each chapter are cameo portraits of Iranians, old and young, men and women from all over the world, whose voices echo aspects of the Persian psyche, and whose dilemmas cast new light on this family saga.

Why did you write this book? Did anything, or anyone, inspire it?

The “immigrant problem” can no longer be ignored in our times. An unprecedented movement of refugees is sweeping across the planet as a result of war, famine, environmental and economic collapse, political and religious prejudice. My own family have effectively been “mohajirs” [migrants] since the middle of the 19th century, so the challenge of finding the balance between assimilation and cultural identity is one I know intimately, and celebrate. I wanted to bear witness to this phenomenon.

Are the characters based on any real-life people?

No particular person is my inspiration in this satire – (please note the caveat at the beginning of the book!) By the same token, certain aspects of human behavior and, in particular, of family relationships, especially under the strain of change and deracination, are similar in every immigrant community.

What is significant in this story is the peculiarly Persian flavor of such behavior. There is a real-life distinction between the Iranian diaspora and other groups of refugees, and the characters in this story reflect these distinctions while also striking a universal chord, I hope.

What is the lesson you’d like readers to take away from this book?

I don’t write books to give lessons, but simply to tell a story. My first book, “The Saddlebag,” was a story about changing points of view. The second, “Paper,” was about what lies between the words. The third, “The Woman Who Read Too Much,” was inspired by the historical figure of Tahirih Qurratu’l-Ayn. And this last book, “Us & Them,” is a piece of self-mockery, an inclusive, and I hope, compassionate satire about Iranians abroad. If we see no difference between “us” and those we call “them,” the story has succeeded!

Is this “Us” and “Them” phenomenon uniquely Iranian, or a general course of life for immigrants and diaspora communities in this day and age?

I think it is uniquely human. It is not just “us” Iranians who create these distinctions, nor just immigrants and diaspora communities who experience the consequences of being treated as “them.” It is a typical human trait, linked to territorial and tribal instincts of primitive survival, that compels us to draw a circle around those we consider to be “our” kith and kin and the dangerous “other.”

At this stage of evolution, the circle has got to be wider, more inclusive, because the danger is precisely to make these distinctions: to survive, we need to realize that “us” and “them” are one.

You have written a number of other books. What would you say are the similarities and differences between this and your other fiction books?

All my books are inspired by Iranian culture, Iranian history, and the Iranian “character.” They all explore the relativity principle from a narrative perspective – how reality shifts and changes depending on each character’s point of view. They all share a certain irony of tone, a certain wit and humor in the use of words, even though they also describe painful, sometimes violent, experiences. And they often deal with women’s “issues” – to my considerable surprise, because I had not intended to do this!

The main difference between this new novel and my previous ones is that it is about now, today, about contemporary life; it is also about people and not about place.

As guest speaker on April 20, 2017, at Iranian Studies, Stanford, California