By Firouzeh Nabavi

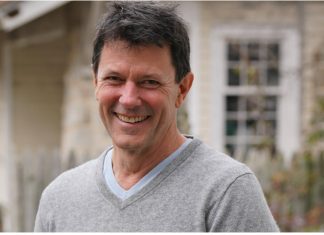

Brigitte Adès is a French journalist and author who, for the past 25 years, has been the UK bureau chief of the respected French foreign-affairs journal Politique Internationale. Married to an Iranian-born businessman, she also has a deep interest in Iran, its people and its culture.

Over the years, Adès has interviewed prominent personalities from the world of international politics — Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher of Britain, President Hosni Mobarak of Egypt, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev — but also great writers such as Arthur Miller and Graham Greene.

Her first novel, published in French in 2017, has recently been translated in English. “Exiles from Paradise” is the story of two young Iranian men living and working in the West who become friends, yet whose trajectories diverge.

Kayhan Life recently interviewed the author about her life and work.

You have close family ties to Iran. What draws you to the country, its people and its culture?

I discovered Iranian culture when I met my husband back in 1982. I found Iranians thoughtful and kind. This open attitude was part of their upbringing. When I met my husband’s family and friends, I was also impressed by their good spirits and philosophy of life. Despite the hardship they had experienced in exile, they were not bitter. They were enjoying life, even though they had left so much behind. What also struck me was that they didn’t hold any grudges. They still had a deep love for their fellow Iranians who had remained in Iran. They were still very much attached to their country, their traditions and ancestral values.

Forty years later, I am impressed to see how well Iranians have assimilated and thrived in so many fields, as engineers, in technology, finance, journalism and so on.

With the benefit of hindsight, a parallel can be drawn between Iranians and the White Russians who left their homeland after the Revolution of 1917. They were also full of talents, had innovative minds, and they came from all walks of life, including the aristocracy. One example was the Nabokovs, who settled in Paris and delighted French society and literary salons. Like the Iranians, the White Russians made a great contribution to create the societies we have today.

Your novel ‘Exiles from Paradise’ is about two Iranians living in the West who feel alienated and cut off from the countries where they live. How did this story come to you?

I am interested in the theme of return. So many people feel displaced and yearn to go back to their country. In the novel, when the young Farhad, aged 24, returns to Iran, he has a myriad of perceptions: the colors in the streets, the scents of the summer nights, the sound of the garden fountains.

In the following chapters, however, Farhad is disenchanted, realizing that this is not exactly the country he knew. Twenty years have passed. Nothing is permanent.

He comes back to Europe and accepts a job offer from a think tank to investigate the spread of radical Islam in the UK, which he realizes is trying to divide Western societies.

I am generally concerned about the way that foreigners and especially Muslims are considered in our countries in the West. I think that a good narrative where two young friends produce acts of bravery in a Western capital can increase empathy, understanding, and mutual respect.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Book-cover-Exiles-1.jpeg” panorama=”off” credit=”Book cover Exiles.” align=”center” lightbox=”off” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

The two men in your novel, Farhad and Reza, are both high academic achievers in the West, yet they take very different paths. Reza, who works for an Islamic charity organization in London, becomes increasingly quiet and withdrawn, and possibly radicalized. Why did you choose to portray Islamist radicalization in your novel?

I wanted to show how difficult it is for some young Muslims to find a meaningful life in a Western capital. Reza, Farhad’s best friend, turns to religion and makes new friends at the Paris Mosque. They help him get a job as the treasurer of a charity organization in London. In the course of his research, Farhad finds out that Reza’s foundation is financed by foreign powers, promotes radical views and possibly hides terrorist activities. When Farhad breaks the news to Reza, Reza gets angry. He had had such difficulties to find a good job and he plainly refuses to believe him. Reza’s attitude and ambivalence illustrates the dilemma of some young Muslims who struggle to find a purpose for their lives in our societies and hold a grudge against the West.

The extensive research I did for this novel led me to visit mosques, Islamic centers and their libraries. Some Mosques, I realized, were infiltrated by radical preachers. Mainstream moderate Muslims attended prayers on Friday evening and trusted their local Imam, not knowing that he was paid by foreign powers to preach radical Islam and Wahhabism. Often, the Imams often strongly discourage the faithful from integrating, saying that assimilation is against Islam. Disoriented youth are particularly vulnerable.

What I also realized was that our democratic institutions and our love for freedom and respect for tolerance made us particularly vulnerable and weak in face of the threat. This is what made me decide to write about radical Islam. Although things have improved since I wrote the book and laws have been passed in Europe, more needs to be done.

What do you hope that readers will take away from the novel?

I hope my readers will rediscover Persian culture and its refinement and will become more respectful of Middle Eastern cultures in general. Most Muslims in our countries want to live in peace, and make a life for themselves and their families. Yet some of them still feel totally out of place and unwelcome. The more they feel ostracized, the more they can fall prey to radical Islam and even terrorism.

You are a journalist and the UK bureau chief of the foreign affairs journal Politique Internationale. Your knowledge of politics and foreign policy is extensive, and you have interviewed numerous heads of state and government. What drew you to politics and foreign policy?

I have been curious about different countries and continents from an early age. At ten, I visited Kiev, Tashkent and Samarkand with my sister aged twelve. My parents, who very much wanted us to be open to the world, had sent us on an organized tour for youngsters.

What really drew me to foreign affairs was the war in Lebanon in 1982. It broke out in the summer, and I remember vividly watching the news, reading the newspapers and not being able to understand the stakes of that war. As I was about to go to Oxford University that September, I decided to switch from studying literature to studying international relations.

Becoming a journalist, getting to interview key players and conveying their analysis has helped me feel more comfortable about world events. I am able to anticipate conflicts and judge the level of danger for myself. My personal background has also played a role in this orientation. My grandparents and parents had to flee France during World War II, and were fortunate enough to be able to return after four years. I guess this has made me particularly sensitive to the concept of displacement and refugees.

What is your next book, and will it also be about Iran?

No. My new novel — which just came out in France — is called “Voices of the Forest” and takes place in Kenya. It tells the story of a young British woman, Vera, who inherits a safari lodge and befriends a British botanist and a local shaman. They all decide to work together to protect the rich variety of healing plants grown locally from being patented by international pharmaceutical companies.

As it happens, when I began to write the novel three years ago, a whole section of the book was devoted to a virus attacking the respiratory systems. The protagonists in my novel were discovering ways to cure the virus with plants. Since then, I have, for obvious reasons, decided to shorten that section of the book.

I hope that writing a novel on this theme will be an eye opener and will prevent these plants from being ‘stolen’ from the locals and allow the revenue from them to be better shared. This novel was very well received in the French language, and hopefully, as with “Exiles from Paradise,” it will soon be translated and published in English.