[aesop_content color=”#ffffff” background=”#0892d0″ columns=”1″ position=”none” imgrepeat=”no-repeat” disable_bgshading=”off” floaterposition=”left” floaterdirection=”up” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off” aesop-generator-content=”The politics of post-revolutionary Iran has been analyzed by states and experts around the world for decades. Understanding the regime’s opaque political structure has become a critical concern for the international community as Iran develops its nuclear program.</p>

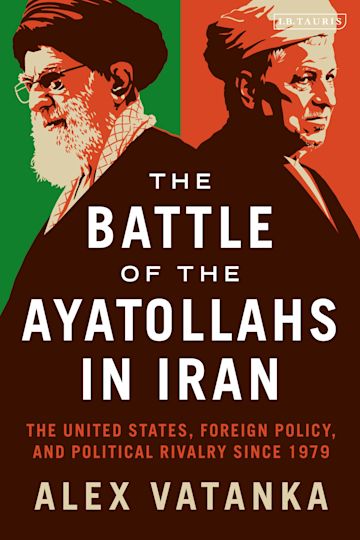

<p>In his new book “The Battle of the Ayatollahs in Iran: The United States, Foreign Policy, and Political Rivalry Since 1979,” Alex Vatanka — a senior fellow and director of the Iran program at the Middle East Institute in Washington — describes the evolution of Iran’s Islamic revolution through the turbulent power struggle between its current Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and its former president, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani.</p>

<p>Speaking to Kayhan Life, Vatanka explains how Khamenei and Rafsanjani became the two single most influential men inside the regime, shaping Iran’s foreign policy, its actions at home and the country’s attitude towards the United States.</p>

<p>”]The politics of post-revolutionary Iran has been analyzed by states and experts around the world for decades. Understanding the regime’s opaque political structure has become a critical concern for the international community as Iran develops its nuclear program.

In his new book “The Battle of the Ayatollahs in Iran: The United States, Foreign Policy, and Political Rivalry Since 1979,” Alex Vatanka — a senior fellow and director of the Iran program at the Middle East Institute in Washington — describes the evolution of Iran’s Islamic revolution through the turbulent power struggle between its current Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and its former president, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani.

Speaking to Kayhan Life, Vatanka explains how Khamenei and Rafsanjani became the two single most influential men inside the regime, shaping Iran’s foreign policy, its actions at home and the country’s attitude towards the United States.

[/aesop_content]

Why did you decide to write about the Islamic revolution in Iran through the lens of the power struggle between Khamenei and Rafsanjani?

I had been working on Iran on and off as an analyst since 2001 and I knew the topic quite well. My parents left Iran because of political decisions that were made, and I became an orphan in a way, having been in exile from a young age. So I wanted to tell the story of, who are these decision makers, Khamenei and Rafsanjani, and how can we tell this story and put a human face to it?

I try to show where they were partners, why they were partners, why they became rivals, and what impact it had on Iran’s standing and position on the world stage.

What do you think Ayatollah Khamenei’s succession process looks like behind the scenes?

Khamenei, who is now 82, is thinking: how do I make sure the transition process is controlled to the maximum extent? Having someone in the presidential palace like Ebrahim Raisi who really owes his entire political career to Khamenei means that he will be doing what he’s told. He won’t be a wildcard. It comes down to who has political power and the imagination to pull it off. A lot will be decided the moment Khamenei dies. Therefore, you want maximum control so you have an understanding and an inner circle of people who can then make sure he’s succeeded by the “right” man.

I think the bad news here is that it won’t be a very different regime, because Khamenei definitely has micromanaged this process. Khamenei has a clear mission to control the succession. He wants somebody who will carry on his legacy, and that’s not a legacy in which Khamenei chooses to go in a different direction to soften his approach and be more inclusive: it’s the opposite. This is a man who to his last breath will say that he knew all along what was right for the country, and that he is implementing it the way he sees fit.

However, while you can have the entire political system engineered in a way that will allow the succession process to happen smoothly, there is still a big risk.

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini [the founder of the Islamic Republic], whatever we say about the man, had a popular base in 1979. A lot of people regretted the support, but he did have a base to begin with. Khamenei had the regime’s consensus in 1989 and while everyone agreed that he was insignificant, he was just good enough as a consensus Supreme Leader, at least to make sure that the regime stayed intact. That was a big fear after Khomeini’s death: the fear that the regime would collapse like a house of cards. Khamenei’s job was to prevent that, and he did.

There’s a wildcard in all of this, which is what the street thinks, and the way Khamenei has isolated the country, the way the economy is suffering. People are angry. And we’ve seen that with the frequency of protests in Iran. So he might have convinced an inner circle of people who share his vision, but if you don’t have the people with you, you only have one thing left — and that is the use of force and repression.

How can Iranian protestors, who are consistently met with violent crackdowns by the regime’s security forces, overcome that kind of response?

Well, this is about magnitude. The regime has in recent years come close to panicking amongst themselves. If you’ve got a few hundred protesters in a couple of locations, then the regime has proven that it can overcome that challenge. If you’re talking about a larger nationwide mobilization of an angry public, then nobody can know what will happen.

Additionally, the regime has arguably never been this split before. The 2009 protests in Iran were the worst crisis the system had experienced, because there was a split within the regime, and that made the 2009 demonstrations last as long as they did, almost 10 months. Right now, you once again have very serious splits within the regime.

The regime can use guns alone to stay in power, but it depends on how much shooting they have to do. It also depends on the actions of the marginalized former elements of the regime, which feel like the system is going in a different and wrong direction.

Why did Khomeini target women when he took power?

It is similar to the Taliban in Afghanistan saying today: ‘We have no issues with women’s rights, as long as it’s within the framework of Islam.’ That is essentially what Khomeini said, and within a few months he had imposed the mandatory hijab.

If you believe in political Islam and you think that Islam has certain conditions set in stone, like the mandatory veil, then you start with that and work your way up to a position where you pretty much have a say on anything that regulates life in a society.

The first group of women to protest came out in the spring of 1979. They knew where things were heading.

Khomeini certainly did not make an issue out of women’s rights before the Revolution. So I suspect that another way of looking at it is that it was as an instrumental way of imposing his will on Iranian society.

You examine the battle between hardliners and reformists in Iran throughout the book. Does the new government in Iran signal the end of that battle?

Today, the founders [of the Islamic Republic] are either dead or dying, and the divisions that used to characterize power politics are no longer there. Are these officials going to be silent and sit there till they die and wither away, or is there going to be a pushback from within the regime against the consolidation of power by the likes of Ayatollah Khamenei? Time will tell.

The duality which my book talks about quite a bit — which didn’t exist in 1979, as Khamenei and Rafsanjani worked hand in hand for power — begins when they then go their separate ways. Now, in 2021, we have a situation where I think we no longer really can justify talking about a duality of the regime.

In your book you quote former President Mohammad Khatami as saying: “Every ideological entity must come to an end, and so will the Islamic Republic.” Do you agree?

I can’t think of any ideological models that have lasted forever, so yes, I think he is stating the obvious and that history will prove him right. But I think you could have argued that if certain adjustments had been made to this Islamic Republic, they could have easily prolonged its existence.

A concrete example is if the Islamic Republic chose to be less involved in the Middle East, because this is a foreign policy that directly isolates Iran, and which, as the new Iranian oil minister [Javad Owji] said, cost about $100 billion in the last couple of years because of sanctions. By being more focused on nation building at home, there would have been more resources to spend on improving the lives of ordinary Iranians. That would have arguably bought the regime legitimacy and some good will.

Instead, the opposite is happening. The region is pursuing what they call the foreign forward defense position, which means that they justify being in various regional theaters.

It’s not the direct cost. It’s not how much Iran spends buying Kalashnikovs that is breaking the bank. It’s the indirect cost of being a rebellious entity and keeping investors out, resulting in a brain drain and all [of the other consequences] in a country that should be one of the top 20 economies in the world.

The history of Iran tells you that this is a country of people who are constantly looking for their voices to be heard, and political representation is a key demand. In the book, I explain that Iran had the first constitutional revolution in the Middle East, probably one of the first ones anywhere in Asia. This shows that there is a civil society that’s hungry to defend its rights, the rights of the people, the citizenry. That’s not going to go away, It’s been part of life for over the last century.

What lessons can the West learn from its engagement with Iran moving forward?

That’s a tough question. There are a lot of issues that are limiting the options of the West at this moment. There is Afghanistan. So if there’s one big headline that screams ‘nation building by Western states doesn’t work,’ that’s it. You could go in and bomb Iran’s nuclear program. That would be the alternative way to stop the nuclear program.

Europe hasn’t figured it out. America certainly hasn’t really figured it out.

There are other things for the West to worry about too. You have countries like China and Russia that will be invested in making sure that American policies on Iran fail, because if they fail in Iran, they can’t be replicated elsewhere, and Khamenei banks on that heavily.

Equally, if you had an Iranian regime that wanted the best for its own national interests, then that would have made life much easier for Western countries to engage. But this is a regime that doesn’t know what it wants either.

The conflict within the Iranian regime doesn’t help Western powers. Which Iran are you talking to? The reasonable Iran, or the revolutionary Iran that is hell bent on kicking the Western powers out of the Middle East?

US readers can buy a copy of the book here.

The book can also be purchased in the UK here.