Porochista Khakpour is an acclaimed Iranian-American author and academic whose memoir “Sick: A Memoir” – about her battle with Lyme Disease – is due to be published by HarperCollins in May 2018.

Khakpour’s debut novel “Sons and Other Flammable Objects” (released in 2007) was a New York Times “Editor’s Choice,” a Chicago Tribune “Fall’s Best,” and winner of the 2007 California Book Award.

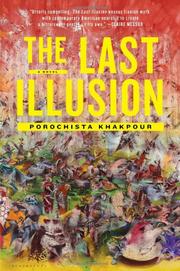

Her second, “The Last Illusion” (published in 2014), also won numerous accolades. It ranked as a Kirkus Best Book of 2014, a Buzzfeed Best Fiction Book of 2014, and an NPR Best Book of 2014.

Khakpour has taught creative writing and literature at Bard College (where she was Writer-in-Residence from 2014-2017), Johns Hopkins University, and Wesleyan University, among others. She is currently a faculty member at the Stonecoast low-residency MFA program and the Vermont College of Fine Arts full-residency MFA program.

Khakpour has taught creative writing and literature at Bard College (where she was Writer-in-Residence from 2014-2017), Johns Hopkins University, and Wesleyan University, among others. She is currently a faculty member at the Stonecoast low-residency MFA program and the Vermont College of Fine Arts full-residency MFA program.

Kayhan Life recently caught up with her for a wide-ranging conversation about her life and writing.

Tell us a little bit about your family background.

I was born in 1978 in Tehran. My parents, at that point, worked for the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran, but in the States, my mother became an accountant and my father a college professor. We left Iran around 1981.

What is the first thing you remember about your new life in the United States?

I remember being very fearful of fireworks and hot air balloons, as I had been scared of bombings from the Iran-Iraq War. So initially it was all trauma. Then I remember Michael Jackson, Cabbage Patch dolls, junk food (I loved hot dogs), and all that other American ’80s stuff. I remember being very worried that Americans would kick us out. I remember this tiny first apartment we had in Alhambra, California, and how temporary everything felt.

Can you tell us about some of the differences between your life at home and in the outside world?

Our home was very traditionally Iranian. Every meal was an Iranian stew, basically. On the walls were color-copied images of Persepolis and ancient Persian art. We spoke Farsi, and my father made sure I could read and write in Persian, with lessons every weekend. I think he didn’t want me to lose my native culture, and I feel so happy he did that. I still feel very Iranian – perhaps more Iranian than American, and I am proud of that.

Outside, of course, it was not that. There were no Iranians in my school. and no one understood where I was from. I was a “resident alien,” a refugee on political asylum who was slowly becoming American.

What was it like for you growing up in the US in the 80s?

It wasn’t quite comfortable. There was quite a lot of anti-Iranian sentiment. I remember knowing the word “camel jockey” way before I knew other words, back when I was learning English. It was also exciting and full of possibility – I remember wanting to be an English-language author in elementary school, and somehow that seemed achievable in America.

Tell us about your upcoming memoir, “Sick.” What was the catalyst for writing this book?

I never wanted to write a full-length memoir, but many ill people who were following my social media posts began to request this of me. Everyone knew I had become debilitated by Lyme Disease for many years. I remember one woman in particular said: ‘You have this gift of writing, so please consider writing something for us.’ I couldn’t say no to that. It seemed an important service, and I knew such a book would have helped me feel less alone. So I wrote it.

What was it about writing that interested you?

I wrote as a way out. I told stories when we fled Iran, at a time when I had no other toys, and saw the value in how it distracted and entertained my parents. I saw that books were cheap, something we could afford. It felt like something I could do. I’ve never wanted to do anything else. And that’s why I write these days – it’s all I’ve ever done, really.

Are you in touch with any friends or relatives in Iran?

Very few now. I am more in touch with bloggers and activists in Iran, who have learned about me and my work through the Internet over the years. They tell me snippets – for a while, when sanctions hit hard, many wrote to me wanting PDFs of books emailed to them because they had lost that access. But often it is just the usual – casual exchanges about culture. I try to follow the youth there closely. For example, I voted for the first time in the last election the way I felt they would have wanted. I followed that all very closely.

What is the first thing you would do if you could go back to Iran right now?

I would love to go back to my family’s home. I would love to go have real kebab. I would love to just walk through the markets. And then eventually I would just travel all over the country. I’m very drawn to the Iranian countryside.

What has been the process of writing like?

It’s not a very easy process. I wrote two novels and finally had the hang of those, and always identified as a fiction writer. Then for years, alongside my fiction, I published personal essays. But those were not really the practice I imagined they might be for a full-length memoir. It’s very hard to write about yourself and your whole cast of characters this way. Structure was a struggle for me, and I sometimes resented being anchored to facts instead of invention.

In your opinion, what made America great for immigrants? And what has changed since the days when you first arrived in the US?

I’m not sure I believe anymore that America was great for immigrants. I mean, that was part of the mission. But the Native Americans and slaves who built this nation were not immigrants. I think America wanted to be a good place for them, but in the end, it might have only been one [for] white immigrants, like the Mayflower set. I mean, even the Irish and Italians were not white enough at some point, and were discriminated against. So it’s not that much has changed. But maybe I have changed. And the events of the past year have certainly made me sour.

What do you hope or want to be the main takeaway after people read your memoir?

It’s hard to predict. I just hope they can see that all of our [life] stories will end in the breakdown of the body, if not the mind. So an illness narrative is the story of all of us. I hope they can see how hard it was to navigate this all, as a woman and woman of color in a country without a proper health care system, with a disease that so many don’t recognize. I just hope for empathy – that’s the most you can ever expect, I think.

#porochistakhakpour #sickamemoir #lyme #lymedisease#bestsellingauthor #creativewriting #harpercollins #iranianamerican#author #bestseller #novel #kayhanlife #buzzfeed