By Rawaa Talass

In Iran, they say it is a sign of eternal friendship when bread and salt are shared among people. This old and cordial tradition is currently being revived in a cultural collaboration between Tehran’s curatorial platform Bread and Salt Projects, and Dubai’s Meem Gallery.

For the first time in the United Arab Emirates, an exhibition — titled “Iran Print” — is introducing visitors to the history of printmaking in Iran. Held at Meem Gallery, an arts space that has specialized in showcasing Arab and Iranian art since its foundation in 2005, the exhibition features 55 prints— including linocuts, lithographs, woodcuts, and silkscreens — by four pioneering masters of Iranian modernism: Parviz Tanavoli, Bahman Mohassess, Charles Hossein Zenderoudi, and Sirak Melkonian.

The exhibition aims “to show some of the most important pieces from these artists,” explains co-curator and co-founder of Bread and Salt Projects Yashar Samimi Mofakham. “People know these artists, but to have their prints being gathered together is, I think, rare.”

A selection of delicate Qajar era prints of animals and military scenes from the 19th century is also on display, reminding the viewer of this sophisticated medium’s longstanding presence in Persian visual culture.

Printmaking involves the practice of stamping an image through an inked matrix onto a surface such as paper or fabric. As a fine art medium, it gained momentum in Iran in the 20th century — in particular, during the 1950s and 1960s when Western-educated artists taught printmaking at notable art schools, such as the Fine Art School of Tehran and the Tehran College of Decorative Arts.

With the goal of turning printmaking into a popular discipline on the local art scene, biennales and contemporary art galleries in Tehran started showcasing prints. Eventually, studios that were specifically set up for printmakers were opened. In the 1970s, the renowned Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art acquired volumes of prints, enriching its world-class collection of Western and Iranian modern art.

In reality, the history of printmaking in Iran stretches back to the days of the artistically prolific Qajar dynasty, in the 18th and 19th centuries, when lithographs were being imported from Russia and Tbilisi to Persia. It was Crown Prince Abbas Mirza who took the initiative by sending students abroad to learn the techniques of printmaking and lithography — eventually opening Iran’s first printing press in Tabriz in the early 1800s.

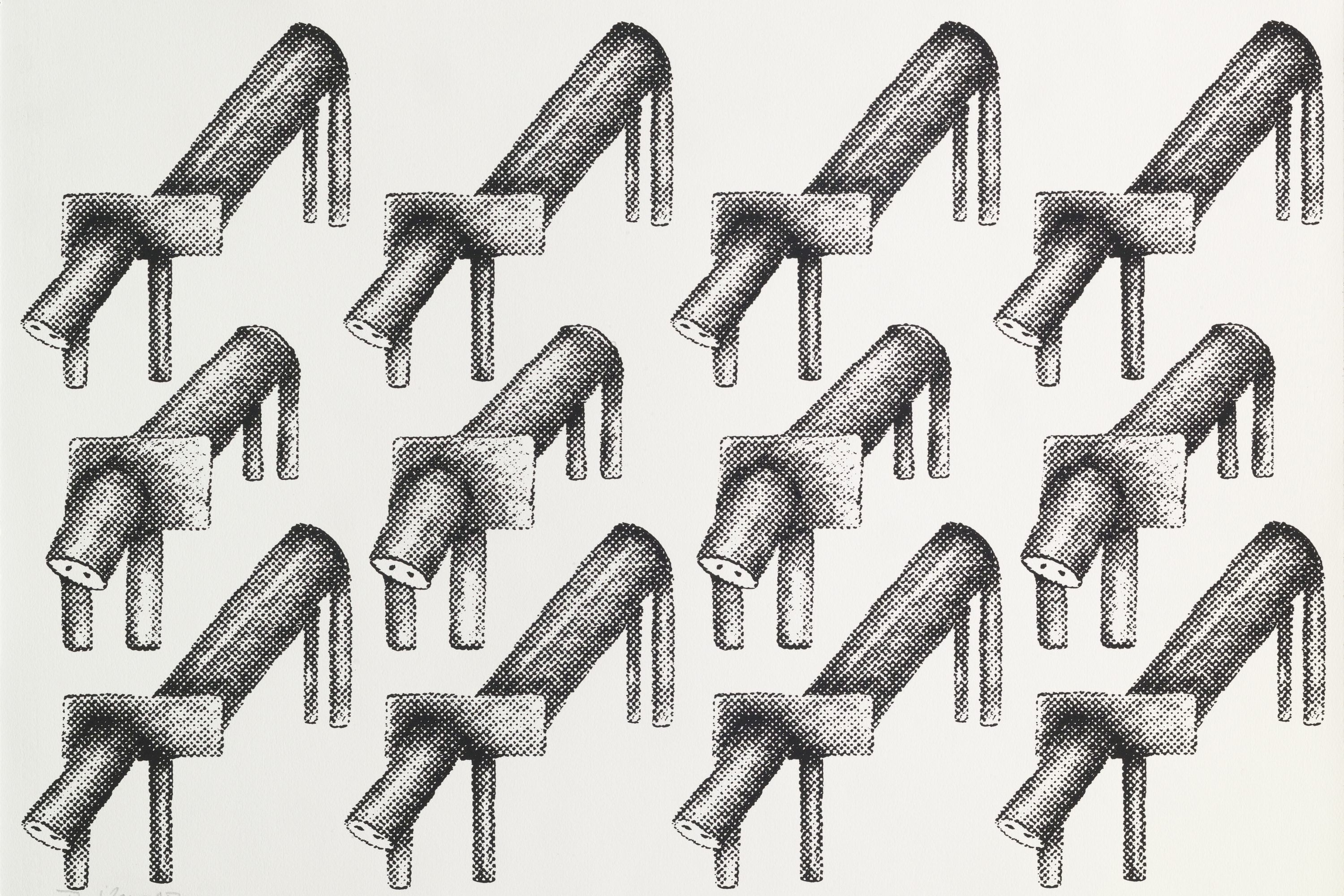

One of the key teachers of printmaking in Tehran was the polymath Parviz Tanavoli, who was born in the 1930s. Although he is known as the ‘father of modern Iranian sculpture,’ Tanavoli pursued printmaking in his formative years, producing more than 100 prints, and continues the practice to this day. On display at Meem Gallery is a group of recently produced silkscreens revealing his long-term fascination in portraying lions, a symbolic cultural icon and onetime national emblem of Iran that has time and time again been depicted in traditional textiles, literature, and folkloric performances. In one of his stylistically modern silkscreens, Tanavoli creates a repetitive pattern of lion tombstones, a reference to the longtime tradition amongst Iran’s lower tribes of placing lion statues on the graves of soldiers and important individuals, according to the curators.

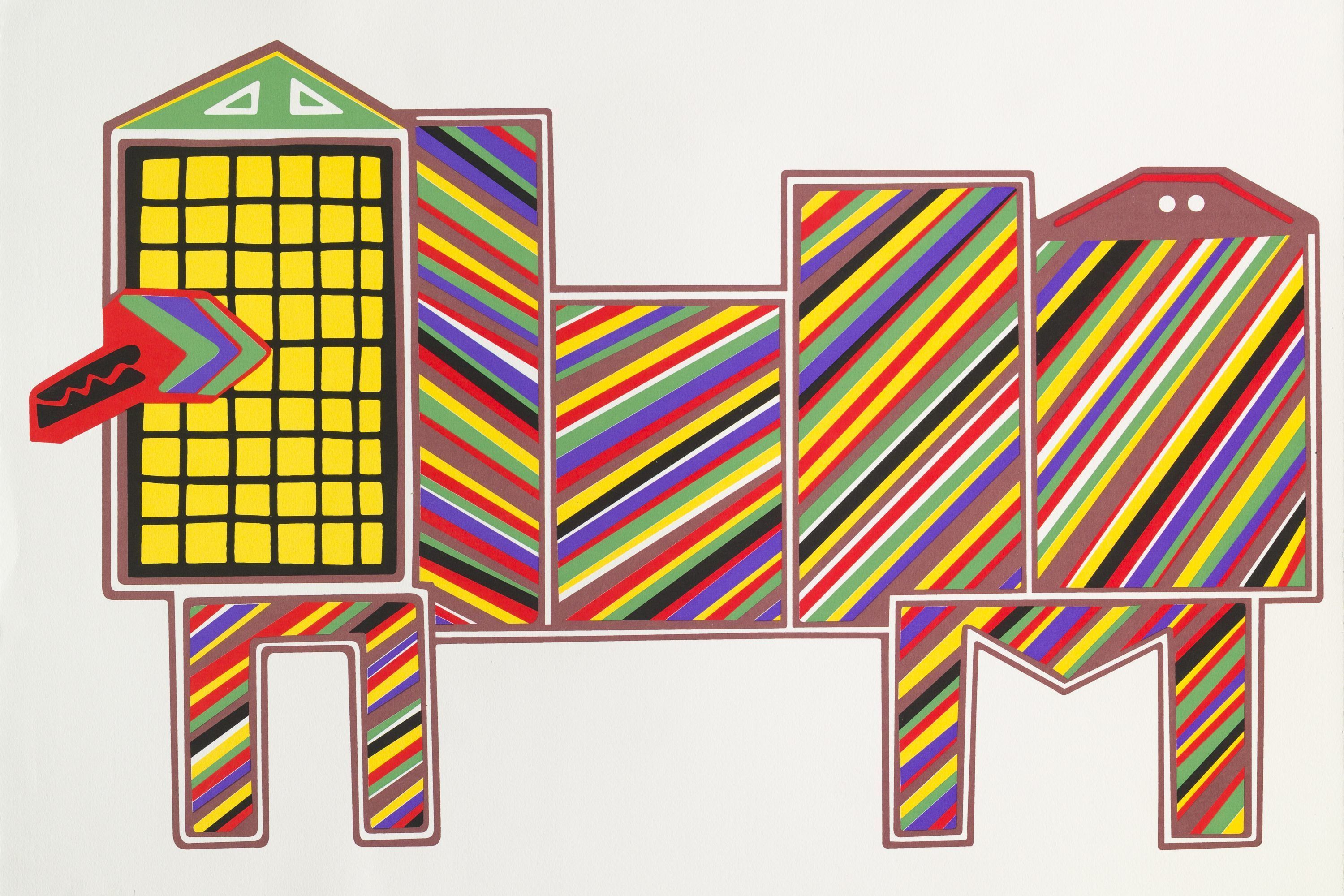

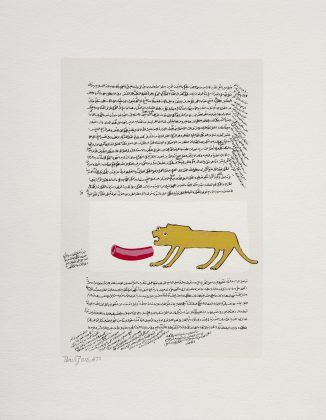

A student of Tanavoli, Charles Hossein Zenderoudi playfully experiments with words, shapes, and vibrant colors. An enthusiast of Islamic calligraphy, Zenderoudi enrolled in the Fine Art College of Tehran University and later became a founding member of the influential Saqqakhaneh movement. In the 1960s, the artist moved to France — where he continues to reside — mingling with the likes of Alberto Giacometti and Lucio Fontana. The exhibition’s curators provide a rare display of Zenderoudi’s prints from 1968, revealing exuberant abstract compositions that are made up of holy verses.

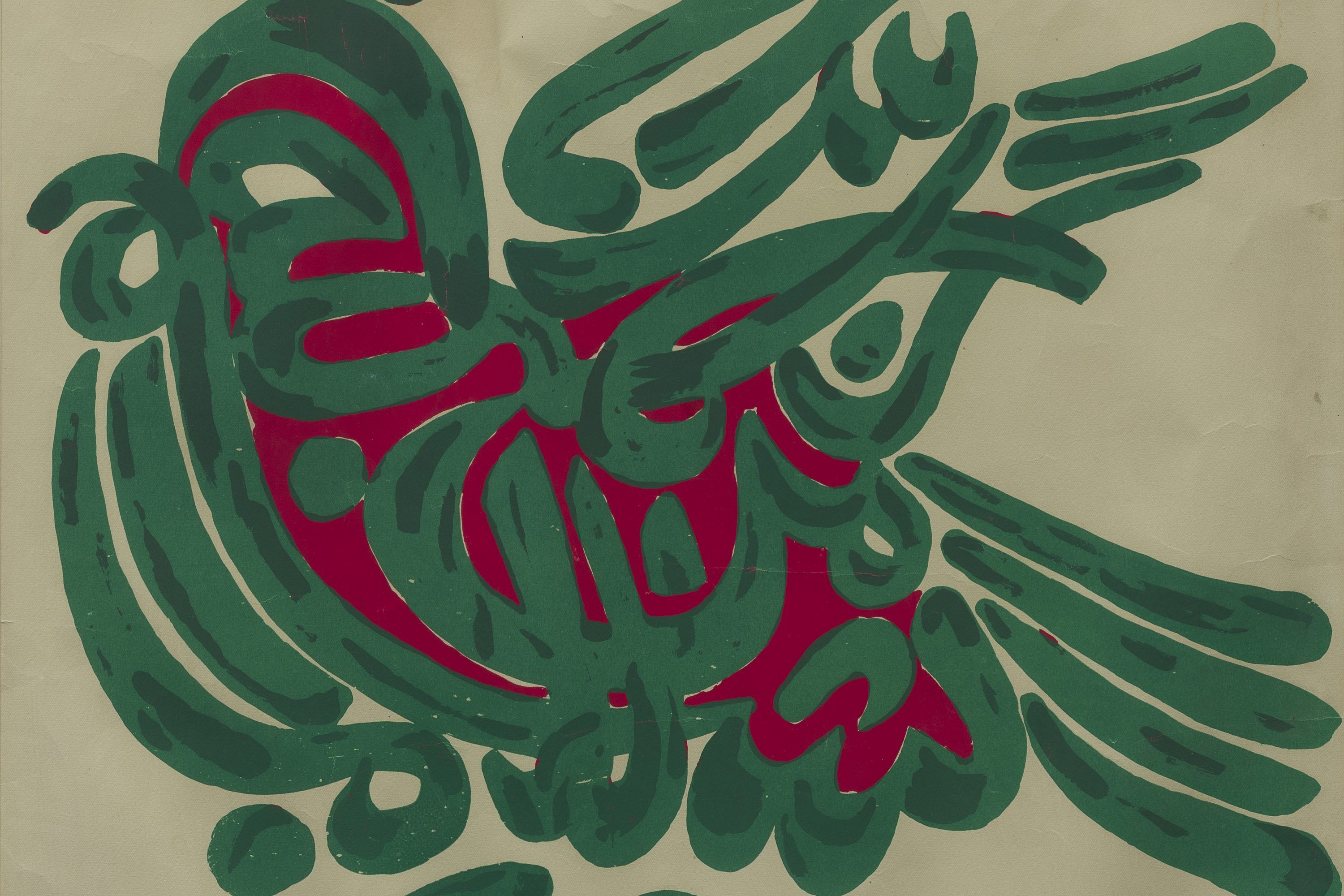

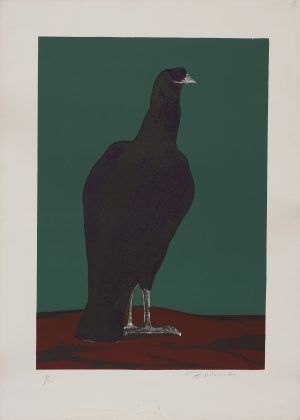

Dubbed the ‘Persian Picasso,’ the Rasht-born and Rome-educated Bahman Mohassess is another showstopper with his bold and dark prints. He depicts birds, or “creatures,” as co-curator Tarlan Rafiee likes to call them. There is a strong undertone of mystery and unease in Mohassess’ imagery, as Rafiee points out: “Mohassess is a creator, so he was creating his own world. When you think of a bird, you think of freedom. But Mohassess’ birds don’t feel free, they’re heavy — like a statue.”

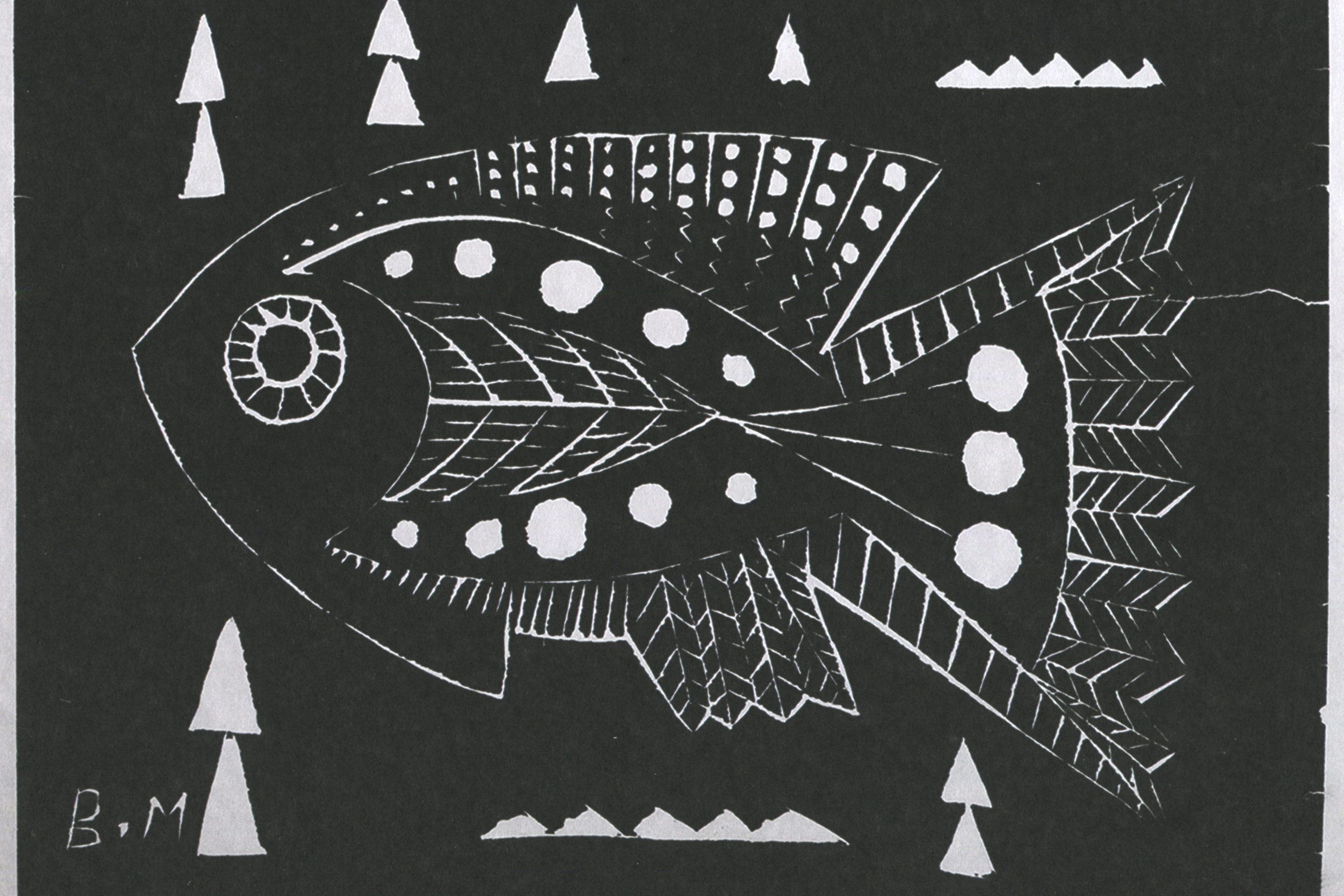

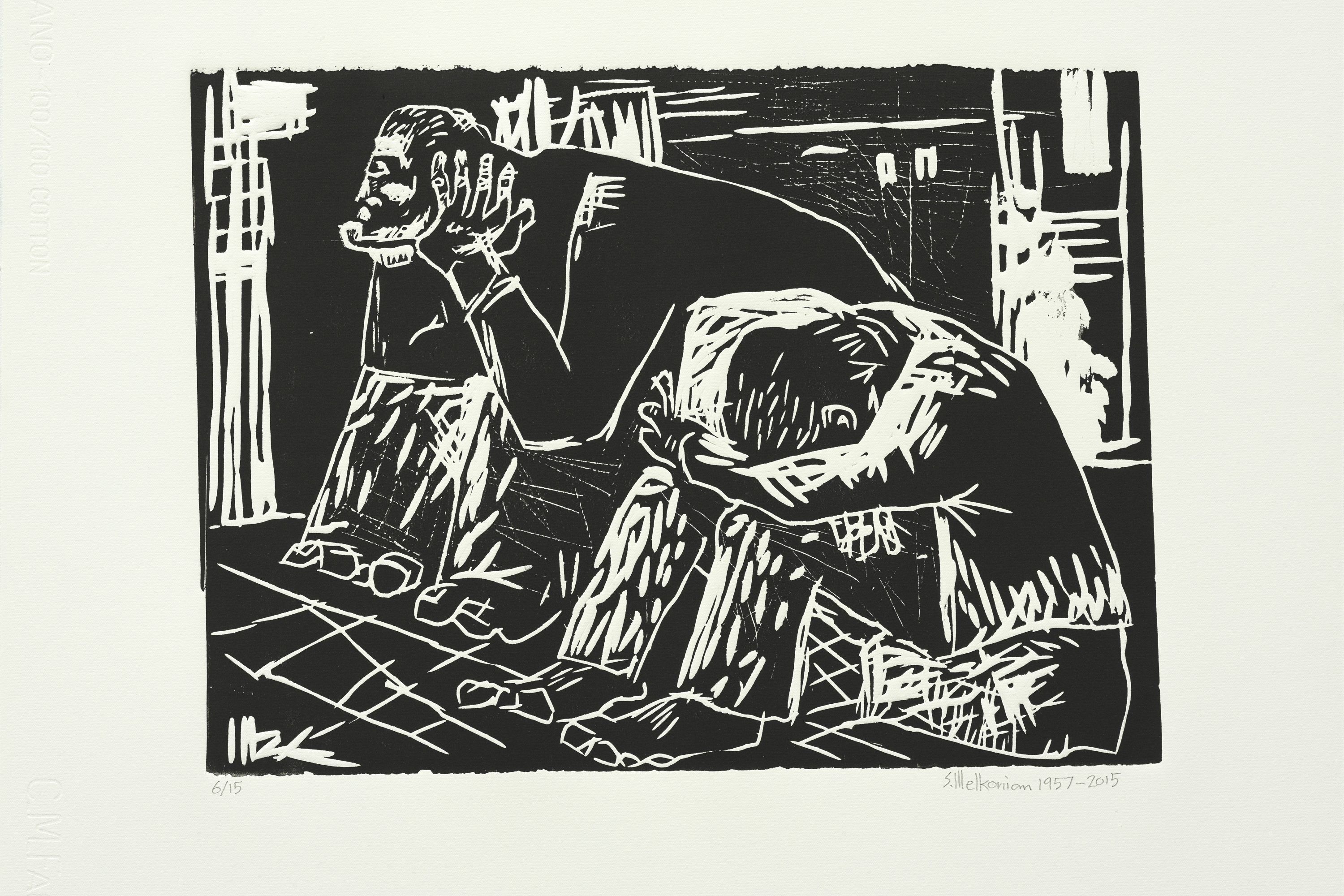

In his expressive black and white linocuts, the Iranian-Armenian artist Sirak Melkonian immerses himself in the world of social realism, delving into the nature of society, specifically the lower and working classes. His style is somewhat reminiscent of the German Expressionists, whose works were dense with social commentary at a politically turbulent time in the early 20th century. One of the prints on display, which shows women breastfeeding, was awarded the Imperial Court Prize at the Tehran Biennial in 1958 — a significant moment for a medium that was not entirely recognized by the establishment.

“Iran Print” runs through Nov. 5 at the Meem Gallery in Dubai.