By Mani Tehrani

In the modern world, gender discussions are focused predominantly on women’s rights, no doubt because of the centuries of discrimination that women have endured. As a result, many artists representing women focus on issues such as equality and a woman’s right over her own body.

Farnaz Zabetian, an Iranian artist based in San Francisco, chooses to highlight her own experiences and those of her generation, opening a window on a range of subjects: from the wounds of the eight-year Iran-Iraq war to maternal love. She is currently working on a new project about the schizophrenic nature of Iranian society. Kayhan Life recently sat down to speak with her.

Do you have an academic background in art and painting?

I went to art school, then got a B.A. and an M.A. in painting. I taught painting for many years in universities in Iran. The day I started college, I was already a painter; I only studied it for the sake of professional development.

I remember that when I still didn’t even know how to read and write, I sent my father – who at the time was always traveling and away from home – letters that were solely visual. The images were descriptions of our daily lives: whether it was during the bombing of Tehran, when I attempted to show my fears by drawing a missile that had hit a house, or during the long summer days, which I recreated by drawing the garden filled with the warm yellow colors of the sun.

What was the first painting you considered professional enough to want to present to an audience?

I was in the second year of middle school, and my parents signed me up for a painting class. I painted a portrait of Nelson Mandela’s sister. It was my very first portrait, and I was very pleased with myself. I gave it as a gift to my father on Father’s Day. When I moved to the U.S., everything happened in a rush and I had to have my friends clean up my studio and send me my stuff. Unfortunately that painting was lost.

Why did you choose Nelson Mandela’s sister?

I just wanted to practice my skills and learn. She was an old woman with a wrinkled face, and it was interesting for me to work on her portrait.

How much of your work is biographical?

The absence of my father, my mother’s constant worries [about him being] thousands of kilometers away on the Iran-Iraq war front, and the wounds left by that situation have had horrible effects on me forever. What I am today is inseparable from my childhood.

Tell us a bit about the exhibitions you have taken part in.

There have been so many. The first goes back to when I was 22 and it was held at the Barg Gallery in Tehran. Aftab Newspaper ran a piece about it and I was so happy and excited I couldn’t sleep for four days. The most recent one was in the U.S., at the Peninsula Art Museum in California, and it had wide media coverage.

Have you produced any paintings that you haven’t wanted to sell?

Have you produced any paintings that you haven’t wanted to sell?

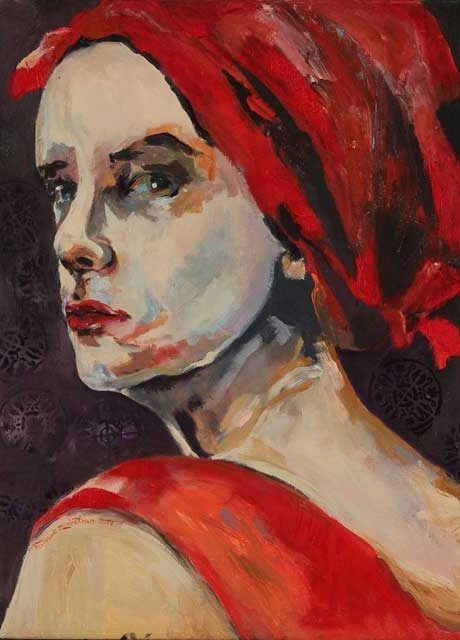

Yes, there was a painting in my latest collection that both the museum and a customer wanted to buy, but I couldn’t part from it. It’s a portrait of a woman wearing a piece of black lace with red dots over her head. The painting attempts to fight taboos; it’s a protest against how we as girls were treated. Whenever people wanted to wish us well as girls, they would pray for us to some day become brides. They made marriage seem like a heaven that would make all our dreams come true.

All little girls have thrown white lace over their heads, worn their mothers’ high heels, and stood in front of the mirror and pretended to be brides. With this painting, I wanted to say that not every lace that is thrown over one’s head is meant to make one’s dreams come true. Oftentimes our womanhood turns into motherhood even before it has had time to mature.

What aspect of women is most attractive for you to work on?

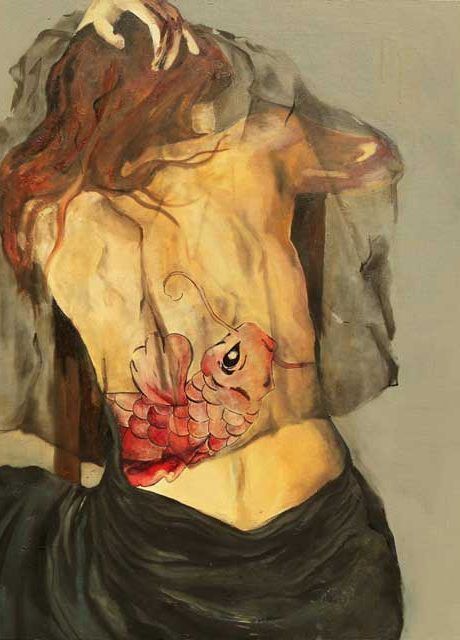

In my work, I picture women who, in one way or another, are going through traumatic struggles with their inner selves. The women of my paintings are all facing romantic melancholia. I believe that the woman’s role as the head of the family, as a creator, is very important. I do not want to deny that beauty and power in any way. But I do think it is very important that the artist expresses the everyday pains of her society as well.

Women have a choice, whether to become mothers or not, but they carry this force within them. Then there comes the expiration date of this force to create, and this is very sad. The woman’s body changes at a certain point in life.

Every collection of mine has its own title, but if we want to find an overarching title for all my works, I would say these are all great women in small frames.

You speak of recreating reality. But in your portraits, the women’s features are deformed and surreal. Do you consider reality being interwoven with imagination, as in poetry?

I do not want to do what the lens of a camera does, simply picturing what I see. I recreate reality from my own perspective. These are my perceptions of reality, reality passed through the filter of my everyday being. In order to keep my personal filters and understanding fresh and up to date, I read, I listen to the news, I keep myself immersed in nature. All of these come together to help me create a work of art.

Iranian artists of the diaspora shows that they do not integrate into their host cultures and remain within the confines of Iranian immigrant society.

The immigrant artist cannot be wholly integrated into the host society no matter how hard she tries. This, however, can become a distinguishing quality, since the artwork she creates has its unique features. For example, in my works, you can find Western combinations of colors and attention to volumes on the one hand, and on the other, the Eastern attention to surfaces, Eastern perspectives, or the two-dimensionality of Eastern culture. You see not only strong expressionism, but also a kind of romanticism and fantasy of objects.

Some artists do not present women from an intellectual perspective, because they consider art and politics separate from one another. They want to avoid whatever is tainted with politics.

What do you think of the coming together of art and politics?

Artists are civil activists, not political activists. At the same time, each artist can have his or her personal political views. I do not want to be sexist, but after having a career for 23 years, I have come to believe that women are portrayed differently by male painters. No matter how close they get to their subject, they still have a different understanding of women.

Women are usually portrayed erotically. As a result, in a culture that is filled with dos and don’ts, this kind of representation becomes political, so the subject of women is deemed political. But this is not how it is. A woman’s representation of women’s issues from a feminine perspective is a civil and not a political activity.

Is there a relationship between your artwork and the music you listen to, the films you watch, and the books you read?

Yes. My studio has a garden, and every fall I go outside and paint while listening to the sounds of the fall. Even though I am a figurative painter and create portraits, when I am surrounded by fall scenery and listen to its sounds, my colors, palettes, and preliminary drafts all get influenced by it. Even one’s food, workout, and health affects the work one does.