By Nazanine Nouri

Feminist icons from pre-revolutionary Iran will be the focus of a solo exhibition by the Iranian-born British artist Soheila Sokhanvari at the Barbican Centre, London’s leading arts and performance complex.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Soheila-portrait-photo-.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”KL./” align=”center” lightbox=”off” captionsrc=”custom” caption=”Soheila Sokhanvari.” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

“Rebel Rebel” (Oct. 7 to Feb. 26) is a site-specific installation commissioned by the Barbican for its high-profile lobby-level space, The Curve, which is accessible free of charge.

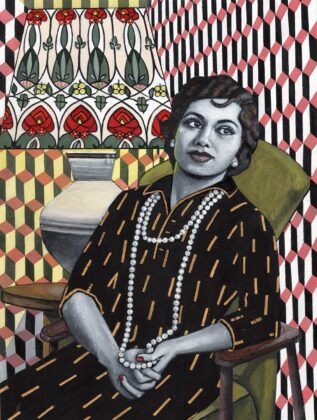

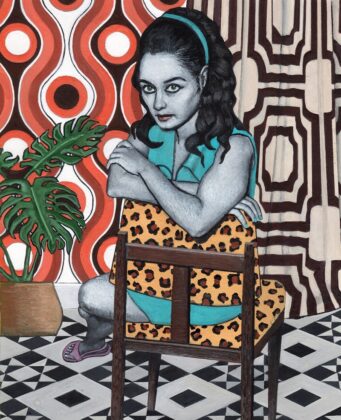

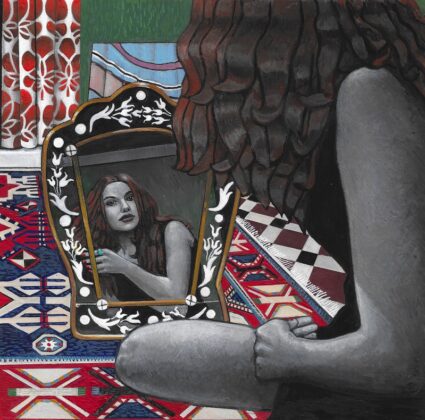

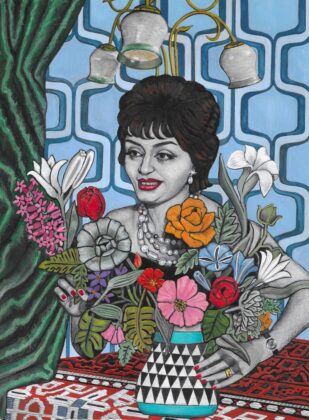

The installation — supported by the Bagri Foundation, Arts Council England, the Soheila Sokhanvari exhibition circle, and the Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery — features 27 portraits painted with egg tempera on calf vellum with a squirrel-hair brush. They will be hung on a vast mural decorated with geometric patterns inspired by traditional Islamic design. The soundtrack, composed by Marios Aristopoulos songs, is derived from songs by celebrated Iranian vocalists of the late 20th century, including Googoosh and Ramesh.

Soheila Sokhanvari was born in Shiraz, Iran, and currently lives and works in Cambridge, United Kingdom, where she is a studio artist at the Wysing Arts Centre. Her work is in the collections of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Victoria and the Saatchi Gallery. She is a graduate of London’s Goldsmiths College and of the Chelsea College of Art and Design.

She has most recently shown work in The NGV Triennial, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne (2020-2021); “Addicted to Love” at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery, London (2019); “Salam Salam,” an installation commissioned by the Magic of Persia Foundation (2018); and “LDWN,” an installation at Victoria Station, which was a collaboration between the Tate Collective and City Hall (2018).

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/SSO-0228-image.jpg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”off” captionsrc=”custom” caption=”Soheila Sokhanvari – Let Us Believe in the Beginning of Cold Season (portrait of Forough Farrokhzad), 2022. Drawing using egg tempera on calf vellum. Painting Size: 13.3 x 15.7 cm 5 1/4 x 6 1/8 in Framed Size: 40 x 30 cm 15 3/4 x 11 3/4 in (SSO-0228).

” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Kayhan Life recently interviewed Sokhanvari about her life and work.

Can you describe your life growing up in pre-revolutionary Iran? How old were you when you left Iran for the UK?

I was born in Shiraz as the second of four children. My father was a fashion designer and owned several fashion stores in Shiraz, designing and making clothes for women and men. My mother was a literature lecturer, so I was brought up with an artistic father and an academic mother.

My childhood was very typical. I went to school, and during the holidays I was reading books, cycling, playing with my dolls, swimming, and climbing walls with my siblings. One thing that separated me from them was that I really enjoyed writing stories and illustrating them in notebooks. My father taught me how to draw and paint, and encouraged me to copy miniature paintings from the book of Shahnameh [an epic poem by Ferdowsi] — we had a large book with printed illustrations. My grandfather used to take me to a teahouse in Shiraz where a naqqal, or storyteller, would tell the stories of the Shahnameh against a painted curtain, and I would be lost in the narrative for a couple of hours.

At school, I got good grades, so when my parents decided to send my brother to be educated in England, I asked if I could go with him. When I had just turned 14, my 17-year-old brother and I were sent to London unaccompanied. We were sent to live and study in different cities almost immediately, which meant that I grew up alone.

Were you exposed to a lot of art growing up?

One of the benefits of living in Shiraz was that I was exposed to a lot of ancient art. My family used to visit Persepolis often. We also visited the tombs of Hafez and Sa’adi as well as the mosques and historic sites. There were no art museums at the time, and my exposure to art was through miniature paintings in book illustrations.

My father was a massive influence on my artistic growth; we used to spend hours together drawing and painting. My parents encouraged me to attend weekly art class held in the headquarters of Shiraz Television from the age of 10 until my departure from Iran.

At school, my teachers were not artists, and art classes were led by someone who also taught another subject. It was so dull and unexciting. Teachers would criticize anyone who could not produce realistic drawing, which is the reason many children stop doing art at an early age. But there was a weekly class in calligraphy and geometric patterning, and I used to enjoy those lessons.

What made you get into art after initially studying biochemistry and working as a research scientist?

I grew up in a matriarchal family, and when it came to choosing a subject to study at university, my mother insisted that art was not an option for me. My choices had to be becoming a doctor, an engineer, or a lawyer. I graduated with a degree in biochemistry and initially worked for Midland Bank. After a year, I left and started as a cytogeneticist at St. Mary’s Hospital, then at the Royal Free Hospital, and finally ended up working for Cambridge University as a research scientist (under my married name Soheila Swanton).

I hated every day of my life for 18 years doing these jobs, to the point of being really depressed. I never actually stopped drawing and painting, so art never left me. Finally, in 2001, I negotiated with my boss to work part-time, and study art history and fine arts part-time.

In December 2005, I left my job as a scientist and started full-time on a post-graduate diploma in fine arts at the Chelsea College of Art and Design. It was the most difficult decision of my life, as I had family responsibilities and a mortgage, and to go from a paid job to becoming a student with an uncertain future was not easy. It was my father who said: “Live your life as you wish, and don’t have any regrets.”

In “Rebel Rebel,” your upcoming exhibition at the Barbican, you pay tribute to 27 feminist Iranian icons of pre-revolutionary Iran. Why?

I left Iran in 1978, and my country went through a cultural and ideological change behind my back, as it were. As a child, I was not at all politically conscious, so I have been left with many questions.

My art focuses on working out what happened during the Pahlavi era.

I have read a lot of books and studied Iran through people’s stories and photographs. After graduating from Goldsmith’s College in 2011, I focused on my family photographs and later became fascinated by our female artists and their stories.

I realized that in the short space of time from the unveiling of women by Reza Shah [the founder of the Pahlavi dynasty] in 1936 until 1979, these women achieved so much, many of them becoming international stars in literature and the performing arts, despite coming from conservative families that did not approve of their career choices. To become an artist, many of these women had to run away from home, or were shunned by their families. After the Revolution many of them were banned and forced into silence. Several of them managed to escape Iran and go into exile. The ones who remained became exiles in their own culture.

As a female artist, I was drawn to these women, who I admired as a child, and decided to create a temple of contemplation for them. I wanted to celebrate them as examples of Iran’s many artistic women, and to show people how talented and amazing they were and are.

Who were these icons and what do they represent in your eyes?

They were writers, poets, dancers, singers, filmmakers, and actors, not all of them well known: artists such as Roohangiz Saminejad, the first woman to stand in front of a camera and act at a time when appearing without a veil in public was taboo. Her film “Lor Girl” (1932) had major political significance. Even though it had to be filmed in India, it enjoyed instant success in Iran.

Still, Roohangiz suffered social ostracism and sexual harassment. She had to change her name and live in anonymity and seclusion until her death in 1997.

The exhibition ends with a portrait of Nosrat Partovi, whose only cinematic appearance was in The Deer (1974). Her inclusion in the show is due to the tragic burning of the Cinema Rex, which happened in 1978 while her film was being shown. The film became one of the last movies featuring an unveiled woman to be screened in Persian in Iran.

Female actors had no training. There were no acting schools, no make-up artists, no wardrobe budgets, no guidance. Yet they managed to make it to the top. Even if the films are not up to our present standards, they are comparable to British Carry-On movies, to the movies of Norman Wisdom, to Bollywood, and even to some Hollywood movies of the time, an age of female objectification and sexualization. To criticize them is like condemning Marilyn Monroe for doing the same.

Your portraits of these icons convey a sense of nostalgia for a bygone era. Why did you choose to focus on pre-revolutionary Iran?

I was trying to work out what happened before the Revolution, since it is the only era of Iran that I know. I decided to focus on the reign of the Pahlavis, from 1925 to 1979. I am therefore visiting historic events and working with photographs of a bygone era. We must learn from history.

These portraits are also filled with traditional Persian patterns. Where did you draw your inspiration for the imagery you used in this collection of portraits?

My father was in the fashion industry and for as long as I can remember, my childhood was filled with images of rolls of fabric in different colors and patterns leaning against the walls. I used to spend hours in my father’s office as he was designing his clothes, so that experience informs my works now.

The reason for the patterning in my art is that in Islamic philosophy, when it comes to architecture, hyper-decoration creates a feeling of delirium in the viewer, making them lose their sense of self and contemplate God. In my art, I use this principle so that the viewer will experience delirium if they enter my painting.

The photographic portraits were found online, and they were often grainy and or with a soft focus. The final image is a mixture of my imagination and the photograph. When I stare long enough at a photograph, it becomes like a cinematic moment: the image is created before my eyes.

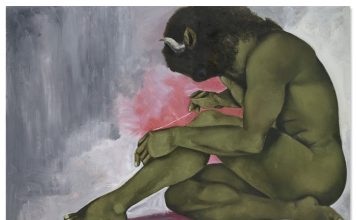

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/SSO-0172-image-scaled.jpg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”off” captionsrc=”custom” caption=”Soheila Sokhanvari, Bang, 2019.” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Your portraits are painted using egg tempera on calf vellum. Can you provide a brief description of your art practice and the materials with which you work?

The technique is medieval and predates oil painting. It involves grinding pigments on a glass slab until the pigment becomes very fine. Then an egg yolk is removed from the white and its contents separated from the yolk skin. Adding several drops of white vinegar and distilled water, colors are then made by mixing this egg to the wet pigment. Traditionally, egg tempera has been done on prepared wood, but also used on parchment or calf vellum, as in the case of illuminated manuscripts. I feel that egg tempera is not only more environmentally friendly than acrylic or oil paint, but also, as with illuminated manuscripts, it lasts thousands of years.

The paintings are traditionally done after drawing out the lines in pencil and then using miniature brushes made from squirrel hair, hashing up the lines to build up each colored section. It takes me 6 to 12 weeks to do a painting measuring 14 centimeters by 16 centimeters.

How did you come up with the title of your exhibition “Rebel, rebel”?

The title comes from a song of the same name by David Bowie (1974). Since these women were rebellious in the face of criticism from a portion of Iranian society who considered them as not chaste or virtuous, the title of the song became a perfect title for their story.

What are the memories of your early life in Iran that you cherish the most? Do you still visit Iran or have any ties with your homeland?

My most cherished memories are spending summer holidays by the Caspian Sea with my family, chasing waves and sleeping under the stars at night, counting the comets. I still have family living in Iran and have visited Iran several times since 2000.

Credit: Courtesy of the artist / Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery.