By Tara Biglari

An exhibition by the contemporary artist Darvish recently opened at the Asia House cultural center in London. The artist joined the world-famous dancer and choreographer Akram Khan for a panel discussion at the opening.

Darvish, who has previously exhibited in Iran, the U.K. and the U.S., has put together a show called “No Man’s Land” — paintings, drawings and films that explore the notion of space through depictions of the universe and of desert landscapes.

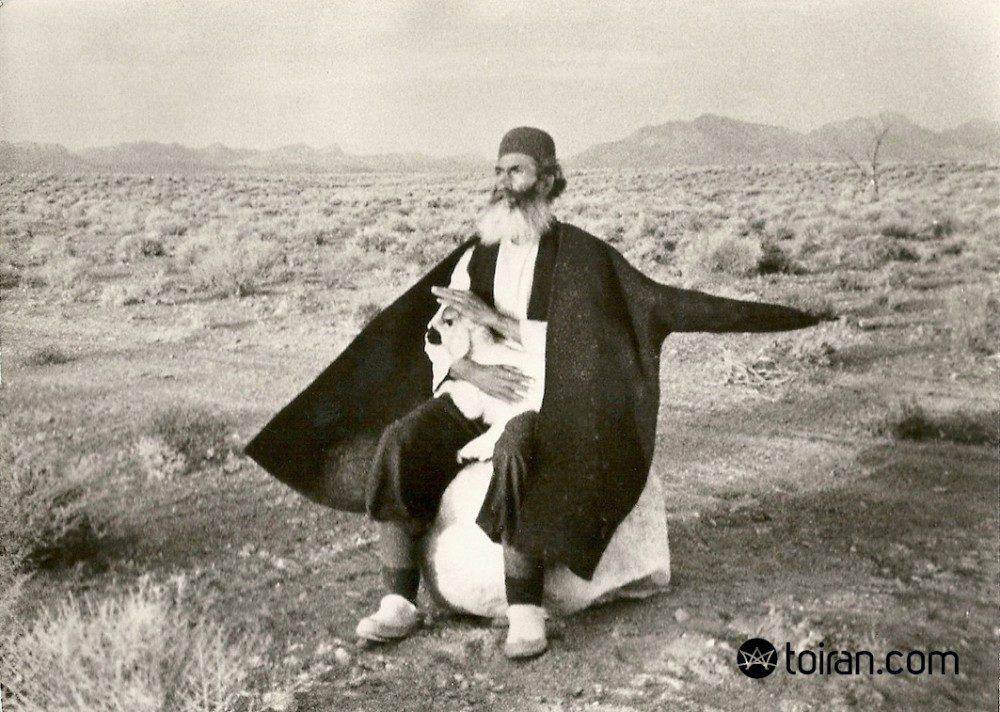

“For me, this is true art, pure art,” Darvish explained. He said his aim was to draw attention to Esfandiarpour’s protest through a tribute exhibition, and added that he felt a strong connection to him.The series was inspired by the late Iranian farmer Darvish Khan Esfandiarpour, with whom Darvish coincidentally shares a name. Esfandiarpour, born deaf and mute, had his land confiscated in the 1963 White Revolution land reforms. He proceeded to spend the next 50 years of his life hanging stones from his dead trees and performing a ceremonial dance in silent protest. The site of these performances, located in Kermanshah, became known as “The Stone Garden.”

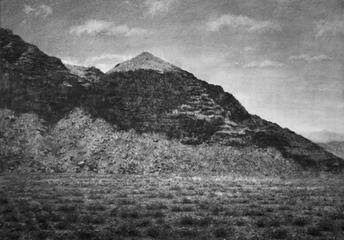

Among the works in the series, the large charcoal drawing “Desert 9” has profound significance for the artist. “The desert is timeless,” Darvish explained. “It could be the past or the future, Arizona or Iran.” Two places located at opposite ends of the planet were, in reality, not all that different: they were both emanations of nature.

“Home,” a large oil on canvas painting, depicts the Earth and the stars in a seemingly infinite universe. Darvish recounted a dream to the audience in which he “went to the wall of the universe,” and when he crossed over, entered a space that turned out to be his own self. “All the patterns in nature – the sea, the wind – it’s all part of us.”

As the conversation wound down, the room came to life with audience members flocking to the small bar and Darvish speaking to curious art enthusiasts.Steering the conversation to Darvish’s roots, Akram Khan asked if his work was political. “Ah, that question,” Darvish joked. He explained how he wasinterested in exploring another side to his art “which offers a richness in culture and knowledge.” Assomeone half-Iranian and half-American, Darvish said he felt a sense of duty to communicate his experiences and feelings about Iran as far as he could. “In that sense, it’s political.”

Meanwhile, in the downstairs exhibition area, some guests made their way into a silent disco, where Darvish encouraged them to simply “let go and move to the art.”