[The views expressed in this blog post are the author’s own.]

I first learned about underground cinema in Iran, over 15 years ago when I watched a screening of an independent Iranian documentary called Epitaph, featuring the untold stories of sex trade workers in Iran after the revolution. The film was made by two prominent Iranian film makers Moslem Mansouri and Lila Ghobady.

The film touched me deeply and was one of the factors that motivated me to start my Iran focused human rights advocacy work. I’ve followed underground cinema in Iran as well as the works of Mansouri and Ghobady ever since, and I am both inspired and impressed. In writing this post I contacted Ghobady who has been living in exile for the past 16 years to find out more about underground cinema in Iran.

It is not a secret that once the Islamic Regime forced its way to power after the revolution, it took full control of all areas of art, including film. Artists were forced to obtain permission, or “mojavez,” for their art work from the Ministry of Culture, before they were allowed to produce or publish their art. Censorship was widespread, and artists were not able to create any form of art that was not aligned with Islamic Regime’s agenda.

Ghobady told me that it was during this time that Mansouri, who had been imprisoned in the early 80’s by the Regime, made two films, “Close Up Long Shot” and “Shamlou: The Poet for Freedom”, without permission from the Ministry of Culture, and used the phrase “underground” for this work. According to Ghobady, “this was the first time the term “underground” had been used to refer to art made in Iran, hence Iran’s underground cinema was born”.

Living under the Islamic Regime’s rule and trying to make independent films was extremely difficult, because making films without permission was against the law and punishable by arrest and imprisonment. Things were made even more difficult according to Ghobady because “filming equipment including cameras were very large and difficult to hide or carry, and it was equally difficult to smuggle films out of the country.”

Eventually many underground film makers including Mansouri and Ghobady had to flee Iran to avoid persecution, but continued to make films in exile. There are also many young film makers in Iran who continue to make short films and independent documentary films inside of Iran, despite threats to their safety, in an attempt to portray the lives of ordinary people under the Islamic Regime rule.

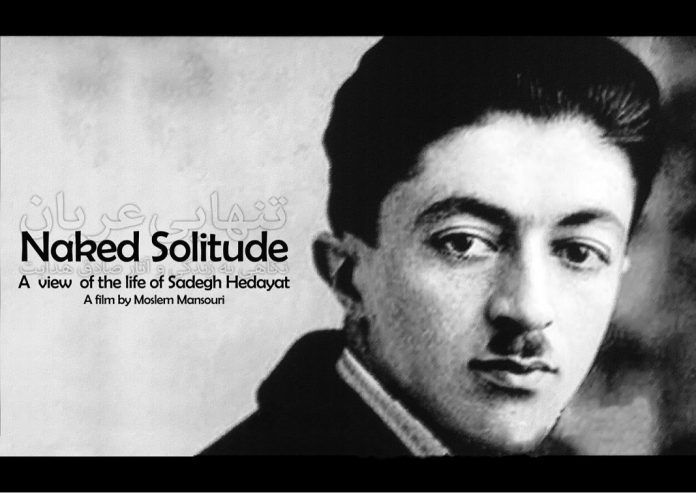

Ghobady and Mansouri for their part continue to make independent films including their latest film, “Naked Solitude,” about the life of the leading Iranian novelist Sadegh Hedayat. This film has been well received and screened in several European cities, with two more August screenings scheduled in Helsinki and Stockholm.

I asked Ghobady why she decided to make a film about Hedayayt, a controversial literary figure of the 20th century Iran. She told me “many books have presented a distorted view of his life and literary work. Censure and distortion of Hedayat’s literary works by the Clergy in his lifetime has continued after his death… This film is an effort to wipe the smear off Hedayat’s face, to portray him as truly as he was.”

It’s unfortunate that we in the West don’t hear much about the work of underground film makers in Iran, and independent film makers in exile as much as we might like, but lack of publicity certainly does not mean lack of activity in the field of underground film in Iran. It must be noted that underground cinema has paved the way for underground music and underground literature, which is the reflection of the unhappiness of artists with the Islamic regime and it’s imposition of severe censorship on artists.

Ghobady is in total agreement and tells me “I believe as long as there is oppression by the Regime, there will continue to be strong opposition, including in the form of underground cinema and art in general, as well as artists in exile who continue to create films under difficult circumstances to oppose the brutal anti human/culture regime that has occupied their motherland for almost four decades…”