By Nazanine Nouri

A new memoir by the late British art dealer Oliver Hoare tells the story of how, 30 years ago, he engineered a clandestine swap between a priceless 16th-century manuscript of the Shahnameh, and a 1953 nude by the American painter Willem de Kooning.

In “The Exchange” (out Sept. 20 and available for order from John Sandoe Books), Hoare, who died in 2018, provides a firsthand account of how in July 1994, on the tarmac of Vienna airport, De Kooning’s “Woman III” was quietly traded by the government of the Islamic Republic of Iran for a significant portion of a priceless 16th-century illuminated Persian manuscript known as the “Shahnameh [Book of Kings)] of Shah Tahmasp,” or “The Houghton Shahnameh,” and universally recognized as one of the world’s greatest works of art.

“The sequence of events that follows was kicked off by a most extraordinary coincidence,” writes Hoare in the preface to the book. “So extraordinary that, however improbable a successful outcome often appeared over the ensuing three years, I always kept it in mind, somehow knowing that the deal – the Exchange – would work.”

“The Exchange” gives a detailed rundown of the chain of events which, over a three-year period, led to the airport swap. It also offers colorful tales of Hoare’s travels through pre-revolutionary Iran in the 1960s and 1970s, and chronicles the evolution of the Islamic art market, of which he was a pioneer.

“The Exchange” gives a detailed rundown of the chain of events which, over a three-year period, led to the airport swap. It also offers colorful tales of Hoare’s travels through pre-revolutionary Iran in the 1960s and 1970s, and chronicles the evolution of the Islamic art market, of which he was a pioneer.

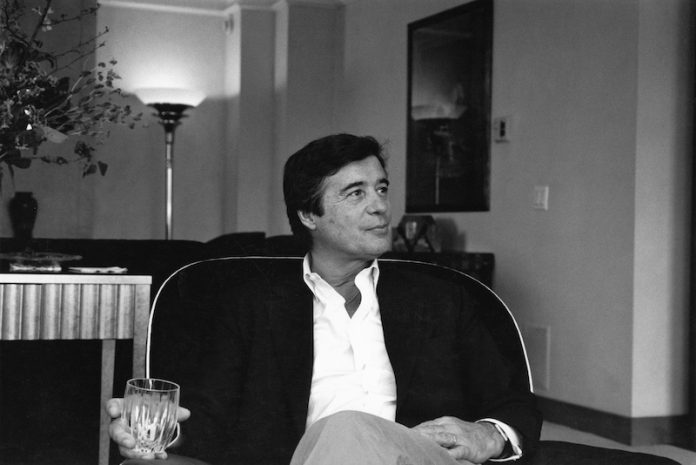

Oliver Reginald Hoare (1945-2018) was one of the most influential dealers in the Islamic art world, “a private dealer with a public persona, and an unquenchable thirst for new adventures,” wrote The Art Newspaper in his obituary in October 2018.

Born to a Russian mother and an English father, who met in Istanbul, Hoare was educated at Eton College and at the Sorbonne’s Institut d’Art et d’Archéologie in Paris. As a child, he was gifted with some ancient Persian coins by his father, and subsequently grew up with a fascination for Persia. He would later travel there by bus and train every summer during his university years.

Hoare joined Christie’s in London in 1967 with a focus on Russian art. But after successfully handling the cataloging and sale of Persian carpets which he had found in the corridors of the Christie’s warehouse, he went on to launch the very first Islamic Art department of any major auction house. He left Christie’s in 1975 and opened the Ahuan gallery in London’s Pimlico area, working as a private dealer with the world’s most important Islamic art collectors and museums.

Hoare’s greatest achievement was, undoubtedly, the exchange between the Iranian government and the Houghton Family Trust to recover a significant part of the so-called “Houghton Shahnameh” in return for De Kooning’s “Woman III.” The painting was a prize possession among the 1,500 works of art held by the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, which had been inaugurated in 1977 by Empress Farah Pahlavi. After the 1978-79 Islamic Revolution, it had been kept hidden in a basement vault (alongside works by Picasso, Monet, Pissarro, Toulouse-Lautrec, Rodin, Giacometti, Chagall, Braque, Max Ernst, Magritte, Munch, Hockney, Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns, Henry Moore, and Robert Rauschenberg).

“The negotiations were full of risk and had taken over three years when the deal finally concluded in dramatic fashion in July 1994,” The Art Newspaper wrote. “Hoare traveled with the Shahnameh from London to Paris, where it was inspected by Iranian art experts before flying on to Vienna airport. The following day, an Iranian government plane landed and off-loaded the de Kooning, finalizing the exchange on the tarmac before returning to Tehran with the Shahnameh.”

In the book, Hoare recalls an encounter with a key figure in the negotiations: the late archaeologist and Iranologist Chahryar Adle, who was one of the intermediaries in the lead-up to the exchange.

Hoare writes:

“I took the train to Paris the next morning, where I met Chahryar Adle in an old-style bistro near where he lived. He was a tall, rangy-looking man, with the brightest of intelligent eyes and an infectious laugh. We talked for many hours and I was relieved to find an Iranian who enjoyed wine as much as I did. He was intrigued to know how I could have written such a letter, the result of which was that the Iranian regime at the highest level was interested in the proposal and wanted to engage. I didn’t reveal that I had an Iranian co-conspirator.”

“‘Before we start,’ he said to me, ‘I have been instructed to tell you that what you are proposing is totally impossible. Nevertheless, in Iran even the totally impossible becomes possible at times.’”

The Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp, or “Shahnameh-ye Shahi,” was commissioned in the 16th century by Shah Ismail – founder of the Safavid dynasty – as a present for his son and successor, Tahmasp.

The 759-page manuscript contained a total of 258 miniatures, and was realized over two decades at the royal atelier in Tabriz by some of the most renowned artists of the time. It was subsequently presented by Shah Tahmasp to the new Ottoman ruler, Sultan Selim II, and remained for centuries in the Ottoman royal library of the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul, before appearing in Edmond James de Rothschild’s collection in 1903.

The carefully preserved manuscript remained intact until its sale by Rothschild’s grandson in 1959 to Arthur A. Houghton Jr. – heir to the Corning Glass Works fortune, and a longtime chairman of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. Houghton initially acquired the manuscript as a possible gift for Harvard University. He then decided to keep it, had it unbound and photocopied by a respected Harvard curator in 1964, and proceeded to dismember it.

Houghton donated 76 folios with 78 miniatures to the Metropolitan Museum as a tax-deductible gift in 1970. He auctioned seven other folios off in 1976, and another 14 in 1988, and sold other pages through art dealers. Pages of the priceless illuminated manuscript are now in such museums and private collections as the Aga Khan Museum Collection, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. and The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art in London.

In October 2022, a single page of the Shahnameh illuminated manuscript was sold at Sotheby’s London for $9.4 million.

When Houghton died in 1990, only 118 miniatures survived. His son Arthur Houghton III chose to sell what was left of the manuscript – meaning 500 pages of calligraphy – in its exquisite original binding.

Starting in 1991, Arthur Houghton III, a foreign-service official then working for the administration of U.S. President Bill Clinton, engaged in secret negotiations with Iranian officials through Hoare.

After three years, an agreement was finally reached. On July 27, 1994, the Shahnameh was traded for De Kooning’s “Woman III” on the Vienna airport tarmac, and returned to Iran.

The De Kooning canvas was later sold to David Geffen, founder of DreamWorks, for an estimated $20 million; the Houghton family received $10.5 million of the total for the Shahnameh, and the rest went to intermediaries.

In 2006, David Geffen resold the De Kooning to the American billionaire Steven Cohen for $137.5 million.

Oliver Hoare worked on “The Exchange” until his death at the age of 73 in August 2018.

“The Exchange” is available for order from John Sandoe Books (click link).

INSIDE LONDON’S ‘EPIC IRAN’ SHOW: 5,000 Years of Beauty, Splendor and Might