By Katy Shahandeh

Sheida Soleimani is an Iranian-American artist born in 1990 to parents who fled Iran in the mid-1980s for political reasons.

Her father was a member of a left-leaning pro-democracy group who, while still in Iran, went into hiding. Her mother served time in the Khoy prison as a result of being his wife.

Soleimani now lives and works as an assistant professor of studio art at Brandeis University in Providence, Rhode Island. She creates elaborate photographic scenes to highlight the politics of the Middle East and satirize the way that both East and West report on them.

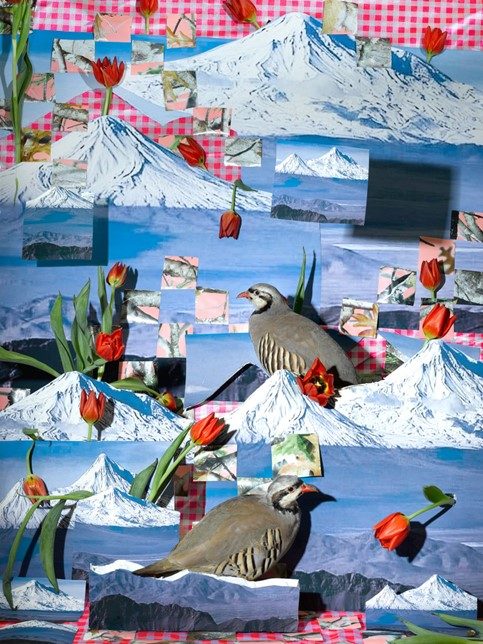

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Picture1.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Sheida Soleimani” align=”center” lightbox=”off” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

She draws inspiration from popular media imagery, adapting and re-contextualizing it to create alternative scenarios in various art forms such as photography, film, sculpture, and theater. Her highly political works aim to document oral histories and bring to light events that are often overlooked or distorted by Western reportage.

Kayhan Life caught up with the artist for a conversation about her life and work, on the eve of the opening of her new exhibition, “Ghostwriter,” at the Edel Assanti Gallery in London.

Can you talk about your latest exhibition, “Ghostwriter”?

This is the story of my parents. It’s something I wanted to make my whole life, but I felt that I wasn’t ethically ready to make this work until now. They always wanted to have their stories told, so when I said that I wanted to take this series of photos, we agreed that they would collaborate with me on them.

This isn’t just my work; it is their work as well – it’s a collaborative practice. The only condition was that their faces would not be visible, so I made paper masks to cover their faces.

There is a growing body of research that suggests that trauma can be passed from one generation to the next. What role does trauma play in your work?

You’re absolutely right. When people hear my parents’ stories, they ask if I’m mentally distraught. But in a way, it was normalized for me. For example, when my mother would put me to bed, instead of bedtime stories, she would tell me about her prison cell. Or my dad, when he got stressed or felt nostalgic, would say: ‘Let’s go for a drive,’ and would tell me about the faces of his friends after they were executed, or talk about his journey through the mountains when he escaped.

My mother worked at one time in a Kurdish field hospital, and she talked to me a lot about the cases there, and the people who died. She also worked with people who had leprosy. So my earliest childhood fear — instead of the devil or monsters hiding under my bed — was that leprosy was hiding under my bed: I’d heard so much about it.

So yes, intergenerational trauma is a very real thing. I don’t think I have post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) like my Mom, but I carry my parents’ pain in a different way. Since they are not able at to tell their stories, and don’t have a way to share that weight or that burden with the world, and since I am a generation for which communication and storytelling is extremely important, I try to tell their stories.

I am also aware that my parents aren’t the only people that this happened to: that this is the experience of many Iranians. But of course everyone has experienced trauma in a different way.

Can you describe your artistic process?

My work is always initiated by an event. For example, To Oblivion was inspired by the unjust executions of women in Iran. I decided to research each case study to unearth the victims’ narratives.

Another series, Levers of Power, started when [Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps Commander] Ghassem Soleimani was assassinated, and then the Ukrainian airliner was shot down [as it prepared to land at Tehran Airport]. I got interested in doing a series of works that discussed the relationship between Iran and the United States and explored the rhetoric of Americans, who always try to figure out who’s bad and who’s good. Maybe both are bad and maybe no one is good!

Everything comes from a specific story or event. I think about how I’m going to address the issue and what source images I might use. Then I build theatrical sets and scenes, collage them, and photograph them.

Apart from being an artist and an academic/educator, you are also a federally licensed bird rehabilitator. What draw you to this?

I am a fixer-nurturer and have always been drawn to creatures that need help. This is something I get from my Mom. When she was in Iran, she was a nurse, and her ultimate joy came from helping people and making them feel better.

But when she escaped and eventually came to the US, she didn’t really speak English. She was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis caused by stress and trauma, as well as severe PTSD which continues to this day. So she was never able to get a job as a nurse in America. Consequently, she really missed that feeling of being useful.

When I was growing up, we lived in a very rural part of the country and there were a lot of animals that were hit by cars or have some sort of injury. My Mom would bring them home and use her nursing skills to help them. I grew up with that, and with my dad, who is a doctor – one who enjoys the public aspect of being a doctor, but would never work in a private practice because he doesn’t do it for profit.

My mother found her outlet in helping animals and I just watched and helped with that. Today, I look after something like 600 or so birds a year. My partner built me a wildlife hospital and clinic in my house. We have oxygen chambers and aviaries, and we get 20,000 worms delivered per week for the birds.

The art and the teaching make it possible for me to fund all of this, but academia and the art world are both very stressful. I wanted to do something that brought me joy all the time, so I took classes and got my license. Now I’m the only person in the state of Rhode Island that does this and people call me daily (my phone number is public) about injured birds that need care.

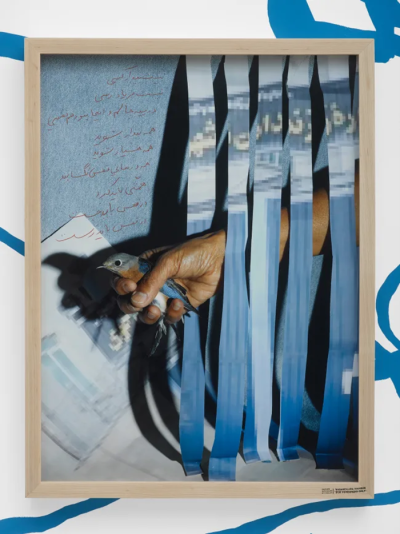

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Picture2.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Khooroos (rooster) named Manoocher, 2021 Sheida Soleimani: Ghostwriter, installation view, Edel Assanti, London, 2023. ” align=”center” lightbox=”off” captionsrc=”custom” caption=”Photo: Andy Keate. Courtesy the artist and Edel Assanti, London.” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

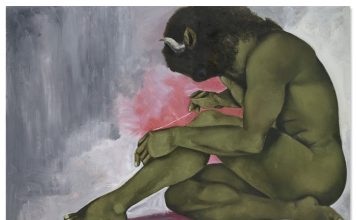

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Picture3.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Noon-o-namak (bread and salt), 2021 Sheida Soleimani: Ghostwriter, installation view, Edel Assanti, London, 2023. ” align=”center” lightbox=”off” captionsrc=”custom” caption=”Photo: Andy Keate. Courtesy the artist and Edel Assanti, London.” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]