By Katayoun Shahandeh

Hanieh Delecroix is an Iranian-born artist living in Paris who left Iran after the Revolution and whose recent work, dedicated to the plight of Iranian women, went on display at the Salon du Dessin in Paris this month.

Prior to pursuing an artistic career, Hanieh worked as a clinical psychologist and psychotherapist specializing in childhood and adolescence, as well as adults with chronic illnesses.

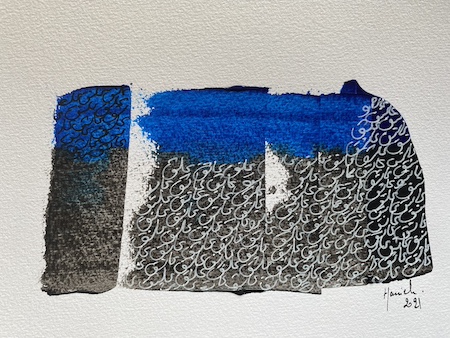

In her artistic practice, she draws inspiration from her dual cultural heritage, fusing lapis lazuli from Persia and the blue hues of France. Her works have been featured in various private and museum collections, such as the British Museum and the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture’s Ithra collection.

In her artistic practice, she draws inspiration from her dual cultural heritage, fusing lapis lazuli from Persia and the blue hues of France. Her works have been featured in various private and museum collections, such as the British Museum and the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture’s Ithra collection.

Following the tragic death of Mahsa Amini in September 2022, Hanieh has dedicated much of her time and efforts to activism, shedding light on the plight of women in Iran through public interventions.

Kayhan Life caught up with Hanieh for a discussion about her life, work and what inspires her most.

Your artwork often combines elements from both Persian and French cultures. Could you elaborate on how this fusion of cultural influences informs and shapes your creative process and the themes you explore in your art?

Art is the embodiment of the artist’s essence, reflecting their history, emotions, and unconscious. My Iranian heritage, juxtaposed with my life in France, imbues my artwork with profound meaning. The concept of exile resonates deeply with me; even though I was three when I arrived in France, I’ve carried the weight of my parents’ exile from Iran throughout my life. Witnessing their struggle to mourn their homeland left an indelible mark on me, shaping my perception of Iran as my own “Paradise Lost.”

Repetition in my artistic expression mirrors the trauma of exile, a theme I explore to repair not only myself but also my family’s collective wounds. Painting becomes a cathartic process where emotions flow freely, unencumbered by intellectualization.

Transmitting my dual cultural heritage to my children is paramount, as it represents the fusion of my Iranian and French identities. Just as a sheet of paper has two sides, I embrace both my French and Iranian identities, recognizing that each is integral to my sense of self.

Considering your commitment to raising awareness about the situation of women in Iran post-Mahsa Amini’s death, how do you use your art as a platform for activism? Can you share some insights into your interventions in public spaces and the messages you aim to convey?

Mahsa Amini’s tragic death compelled me to break my silence and take a political stance, a decision I deeply regret not making sooner. Witnessing the courage and resilience of Iranian youth protesting for their freedom ignited a sense of responsibility within me. As an artist and psychology graduate, I felt compelled to amplify the voices of Iranian women and people by raising awareness among my French compatriots about the injustices they face. Using social media, museum installations, and university engagements, I initiated a campaign to shed light on the Iranian situation and garner international support for the Iranian people. The installation titled “Woman – Life – Freedom – Equality – Fraternity,” displayed six days after her death, was described by Radio France Internationale as “the first politically committed artistic action for women’s freedom in another country to be openly displayed in cultural and artistic institutions in France.”

Inspired by a story shared by Pierre Rahbi, a French philosopher and agronomist, I was reminded of the power of individual action. The story recounts a bird tirelessly carrying droplets of water to douse a forest fire, despite the scepticism of a monkey. When questioned about the effectiveness of its efforts, the bird responded, “I’m certainly not going to put out the fire, but I will have done my bit.” This analogy resonated deeply with me, reaffirming the importance of each person’s contribution, no matter how seemingly insignificant, in the collective pursuit of justice and freedom.

Your background in clinical psychology is intriguing. How has this training influenced or shaped your approach to art, especially in conveying emotions or messages through your artistic expressions?

Studying psychology has deeply influenced my journey as an artist. Both art and psychology share a common thread of emotion.

In my practice as a psychologist, I learned to listen to patients and interpret their emotions, understanding that their subjective experience shapes their reality. Similarly, in art, the emotional response elicited by a work is what makes it unique. There’s no consensus on how art should be perceived; each viewer brings their own interpretation, making the artwork come alive. Just as therapy involves an unconscious dialogue between patient and psychologist, art creates an unconscious exchange between artist and viewer. The act of admiring a painting can be cathartic, allowing individuals to idealize the artist and ultimately, themselves.

I recently presented my work at a symposium on museum therapy, inspired by initiatives like medical prescriptions for museum visits in Canada. My focus, as both a psychologist and an artist, centers on emotion, particularly the concept of tenderness. Tenderness, often overlooked, reveals much about a person’s character.

Could you share some of the challenges you have faced, either as an artist or an activist, in trying to bring visibility and awareness to the situation of women in Iran? How do you navigate these challenges through your art?

Gaining acceptance for my installations in universities and museums proved to be the most challenging aspect of raising visibility for Iranian women. I invested significant time in networking and sending emails to secure agreements, navigating hierarchical structures to garner support. Operating without the backing of a gallery or association, I financed the entire project independently, covering expenses such as paper, printing, transportation, and accommodation for events like the Cannes Festival.

In many instances, institutions either did not respond or cited the sensitive nature of the Iranian topic as a reason for non-involvement. Even when agreements were secured, institutional communication about the installations was often lacking, necessitating my personal efforts in creation, advocacy, production, and promotion. However, through perseverance and the support of remarkable individuals, including the Iranian diaspora, I overcame these challenges. The solidarity witnessed in this movement, where everyone contributed in their own way to support the Iranian people, was deeply inspiring. In moments of despair, the courage displayed by Iranian youth served as a reminder of our obligation to persevere and never give up.

What upcoming projects or themes are you passionate about exploring through your art, considering your dedication to activism and advocacy for women’s rights?

This summer, as the godmother of the Iranian Pavilion at the Avignon Festival, I exhibited a series of large canvases, two of which were dedicated to Iranian women, bearing messages of empowerment in Farsi and French. However, these canvases, along with three others, were stolen before my solo exhibition “All the Flowers know the Straight of the Wind” in the south of France. Now, fueled by the loss and inspired by the resilience of Iranian women, I plan to create 50 new canvases dedicated to them and to all those suffering, particularly children and families torn apart.

In March, I will showcase a series of paintings at the Dessin Fair in Paris, previously exhibited at the Palais de Chaillot, paying homage to dance and the liberated female body, a tribute to Iranian women’s love for dance. In April, I will participate in a conference on Iran, featuring an exhibition of my work and the screening of my short film “Our Sequoia Garden,” chronicling my father’s exile. Additionally, I am exploring the possibility of an exhibition in South America.