By Kayhan Life Staff

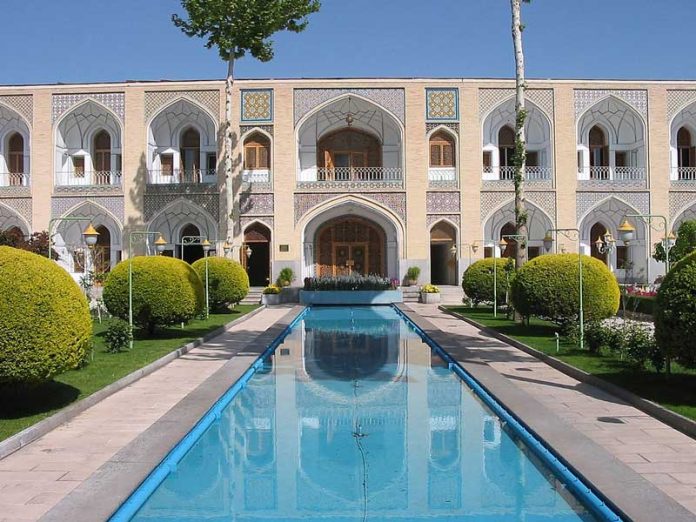

Professor Mehdi Ebrahimian, who designed the legendary Shah Abbas Hotel in Isfahan, passed away on July 11 in Tehran. He was laid to rest in the Rezvan Garden cemetery, at his own request, alongside other honored artists of the city.

Ebrahimian’s passion for the revival of historic Iranian design was evident in his reconstruction of the Shah Abbas Hotel. As the chief architect, he guided and trained local workers and contemporary artists to create the grand spaces that we see today, which evoke the rich cultural legacy and grandeur of the Safavid and Qajar dynasties.

His designs transformed the 300-year-old hotel into an extraordinary and prestigious edifice that is known as one of the most beautiful hotels in the world. Even the furniture was designed by him, and hand-crafted by the renowned Iranian master, Javad Chaichi.

Mehdi Ebrahimian was born in 1938 in Isfahan, and developed a love of art in his youth. He studied at the Isfahan Academy of Fine Arts under the supervision of Professors Poursafa and Isa Bahadori.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Mehdi-Ebrahimian.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Professor Mehdi Ebrahimian. KL./” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

In the early 1960s, he was one of the few Iranian students to obtain a scholarship to study in France. He went to Paris for a four-year course in interior architecture. He also studied painting and mural art for a year before returning to Iran.

Ebrahimian immediately began teaching at the School of Decorative Arts. He established his own office and worked there until he was invited by Minister of Culture Mehrdad Pahlbod to carry out the interior decorations of the international Shah Abbas Hotel in Isfahan.

At the time, the hotel was under French management, and its design was entrusted to Madame Augier. It was designed in the style of the Negresco Hotel in Nice.

The young engineer enlisted the help of 150 other young individuals to complete the interior architecture of the Shah Abbas Hotel. As he once recalled, “Iranian children are very talented, so after a week of training, they worked like master craftsmen.”

He and Dr. Farhang Mehr submitted six grand designs to a judging panel in the presence of the Shah of Iran, and his designs were approved by the king.

“One day, the Shah, accompanied by the Queen and the King of Thailand, came to Isfahan,” he later recalled. “We took them to the royal wing of the Shah Abbas Hotel. Then, for about two and a half hours, we visited the entire hotel. I explained to them the sections that I had decorated. They greatly liked it, and after returning to Tehran, the Shah sent me a Medal of Homayoun.”

Ebrahimian applied a similar style in his designs for an Iranian restaurant in the famous Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York and even created details such as dining utensils with Iranian patterns.

And he again drew inspiration from ancient Iranian art in his designs for international art exhibitions in countries such as Afghanistan, Canada, Japan, and Kuwait. For example, the Iranian pavilion at the Montreal Exhibition was inspired by the intertwining and ascending motifs of roses on the tiles of the Seyed Mosque in Isfahan.

He produced Iranian-style mirror work and plaster work for the residences of Iranian ambassadors in Paris, New York, Brussels, and Moscow.

Ebrahimian was also a skilled painter and craftsman. When he met his artist wife, Violet Dehghani, also an interior designer, he was working at the newly established handicrafts center, part of the Ministry of Economy.

Together with Professor Mohammad Naraghi, they adapted authentic artistic techniques and designs, showcasing Iranian artistry in household and everyday items at their handicraft gallery, Zinatsara, in Tehran. Ebrahimian delved further into his cultural heritage, drawing inspiration from and executing his paintings, sculptures, furniture, and decorative pieces using design elements from Persepolis and other ancient Iranian sites. .

As one of the pioneers of Iranian handicrafts, he was frequently consulted and his works were published in numerous publications. His name is mentioned in the works of the eminent historian Arthur Upham Pope, including “A Survey of Persian Art: From Prehistoric Times to the Present,” as well as in Jay and Somi Gluck’s “Survey of Persian Handicrafts.” He has also been referenced and featured in various news articles, television programs, and exhibitions.

Ebrahimian’s portfolio highlights his involvement in the design and supervision of 10 metro stations in Tehran, the design of the Shah’s private palace in Lavasan, the interior design of the grand international Hotel in Kerman, the design and construction of more than 12 residential buildings in the United States (New York, New Jersey, Washington DC, and California), and the design and supervision of more than 50 residential projects in France and Germany. Additionally, he contributed to the restoration and reconstruction of the Iranian Embassy Gardens in Paris and the Narenjestan garden and courtyard in Shiraz.

Ebrahimian lived for several years in the United States, but returned to Iran where he spent the rest of his life.