By Kayhan Life Staff

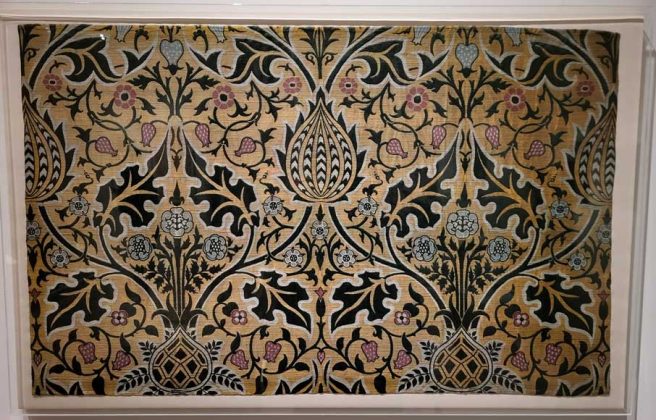

A new exhibition in London showcases the impact of Middle Eastern and especially Iranian art on the pioneering 19th-century interior designer William Morris.

“William Morris & Art from the Islamic World” is on view at the William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow, north London, and will run until March 9.

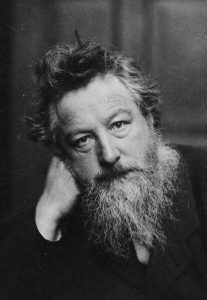

Morris (1834-1896), a key figure in the British Arts and Crafts Movement, introduced groundbreaking innovations in design, creating and producing home furnishings, wallpaper, interior decor, carpets, and textiles. His work cemented him as one of the pioneers of modern interior design worldwide.

Morris was a polymath: an artist, craftsman, poet, and social activist. Deeply committed to social justice and the working class, he frequently wrote poetry addressing the struggles of people experiencing poverty.

Yet he was also a sharp and strategic businessman, employing innovative marketing techniques and bold financial maneuvers to outpace his competitors and dominate Britain’s interior decoration industry for years.

Morris had a deep passion for the art of Middle Eastern countries, particularly Iranian art. Despite never traveling beyond Italy, he gained a profound understanding of this art through a diligent study of literature, direct examination of museum artifacts, and visits to shops selling Middle Eastern crafts.

He collected Middle Eastern art for his personal collection and served as a purchasing advisor for the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum). Under his guidance, the museum acquired one of its most significant and valuable works, the Ardabil Carpet (circa 1539-40), created during the Safavid era (1510-1736). This carpet is one of the largest and oldest dated carpets in existence.

In 1877, Morris wrote about encountering an Iranian carpet from the reign of Shah Abbas I (known as Shah Abbas the Great, 1571-1629), which left him spellbound. He expressed amazement at the intricate designs, remarking that he could not fathom how such patterns were created.

He also famously remarked: “To us pattern-designers, Persia has become a holy land, for there in the process of time our art was perfected.”

Born in 1834 in Walthamstow, London, Morris was the first-born child in a wealthy family and was raised in a traditional middle-class environment. His parents were surprised by his decision to pursue art instead of following a more conventional church vocation.

Eventually, Morris and several friends founded a prosperous interior design firm in London, which came to be known as “Morris & Co.”

Morris aimed to revolutionize interior design during the Victorian era in Britain. He was driven by the belief that art was a fundamental human need and determined to make art accessible to the public in their everyday lives.

In 1877, he famously said: “I do not want art for a few, any more than I want education for a few, or freedom for a few.”

Morris was deeply repulsed by the harsh realities of industrialization, which he believed had resulted in overcrowded slums, polluted cities, widespread disease, and environmental degradation.

A champion of social justice and the revival of craftsmanship, he advocated for the preservation of historic buildings and the responsible use of natural resources. His progressive ideas were groundbreaking for his time.

Known for his tireless work and creativity, Morris’s doctor remarked upon his death in 1896 that his life’s accomplishments surpassed what ten men might achieve in an entire lifetime.

His collection features various Middle Eastern artworks and crafts, including carpets, textiles, metalwork, and ceramics, primarily from Iran, Syria, and Turkey. While some items have been lost over time, the majority have been carefully preserved and documented and are now displayed in this exhibition.

The preservation of William Morris’s collection owes much to the diligent efforts of his daughter, May Morris (1862-1936), who took great care in safeguarding these pieces.

This exhibition reexamines several formerly undervalued works, highlighting their significance and influence on Morris’s art.

Morris aimed to revolutionize the Victorian interior design industry, drawing inspiration from the art of the Middle East. He delved into the region’s decorative patterns, particularly those found in Iranian crafts such as carpets, textiles, architecture, and ceramics, as well as similar objects from other Middle Eastern countries.

His collection includes several delicate silver pieces from the Safavid and Qajar periods (1789-1925) featured in the exhibition.

Unlike Western art, where the human form is often present, traditional Middle Eastern and Iranian art typically avoids human depictions due to religious restrictions. Instead, it is dominated by designs featuring animals, plants, flowers, leaves, and other objects arranged harmoniously, abstractly, and aesthetically. Western art, unconstrained by such prohibitions, frequently includes human figures in interior décor, wall paintings, and carvings.

The Islamic ban on human representation led to the development of complex geometric and abstract patterns in art. Morris recognized these unique elements in Middle Eastern art and seamlessly integrated them into his designs.

In the 1870s, Morris began researching and collecting Middle Eastern art and crafts. His collection included pieces he advised on for museum acquisitions and designs for wallpapers and textiles that closely resembled Middle Eastern artifacts.

These works demonstrate the profound influence of Middle Eastern art, particularly Iranian art, on Morris. They highlight the cultural exchanges between Victorian Britain and the Middle East, which became increasingly common during this period.

Morris believed that genuine authenticity in art and design came not from striving for innovation but from a deep engagement with tradition and craftsmanship. He held that the past lives on within us and shapes the future we create. According to Morris, artists should draw inspiration from history while blending it with their unique style and vision.

Morris’s experiences and experiments in designing carpet patterns were deeply influenced by historical examples from Central Asia and Western Asia, particularly Iran and Turkey. These designs were showcased in “Morris & Co.” exhibitions, sold in various venues, and found in private collections and museums.

Through his meticulous study of Iranian carpets, Morris thoroughly understood the weaving techniques involved. As his knowledge grew, so did his design approach, which evolved significantly.

In the 1880s, his patterns transitioned from intricate floral motifs to simpler compositions, often featuring branches and minimalist elements. These designs resembled those he had studied in glazed ceramics.

Morris also illustrated a handwritten copy of the Rubaiyat (quatrains) of Omar Khayyam (1048-1131), translated by the English poet Edward FitzGerald (1809-1883).