By Nazanine Nouri

Habib Elghanian was one of the most prominent industrialists in pre-revolutionary Iran. From modest beginnings, he worked his way up to running a business empire in plastics, mining, real estate, construction, and aluminum. He was executed in May 1979, after an Islamic Revolutionary tribunal sentenced him on charges including corruption and associations with Israel.

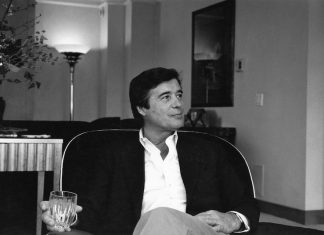

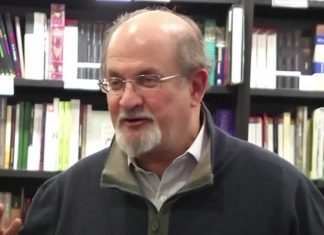

His granddaughter Shahrzad Elghanayan — a journalist who was born in Tehran and raised in New York — has published a tribute to him titled “Titan of Tehran,” with a foreword by Charles J. Hanley, a Pulitzer Prize-winning former correspondent of the Associated Press.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Sh_elghanian2-scaled.jpeg” panorama=”off” credit=”(Portrait by Patrick Sison)” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” caption=”Shahrzad Elghanayan. ” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

In the book, Elghanayan tells the story of how her grandfather went from being a poor Jewish boy living in a Tehran slum, to working as a secondhand clothing and watch trader, to becoming one of Iran’s captains of industry.

Habib Elghanian was also the leader of the Iranian Jewish community, which counted as many as 80,000 members in the 1960s and 1970s. During the Pahlavi era, a period of rapid assimilation, Iranian Jews played a key role in the country’s modernization.

Back in 1940, 80 percent of Iranian Jews qualified as poor; in 1979, only 10 percent did, the rest having integrated the middle classes and Iran’s economic and industrial elite.

Today, Iran’s Jewish community has dwindled to an estimated 10,000 members.

Elghanayan now works at NBC News as a senior photo editor. She previously worked at Bloomberg News and at the Associated Press, as a supervisor on the national photo desk. Before getting into journalism, she was a researcher at the Freedom House human rights organization.

Kayhan Life recently reached out to Elghanayan to ask her about her illustrious grandfather and about the writing of “Titan of Tehran.”

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/TitanOfTehran_Cover-Final-1-scaled.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Titan Of Tehran. ” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Why did you write this book?

I wrote this book to reconstruct the facts about my grandfather’s life and death so that his story would not get lost in the mists of history.

Your book delves into Iran’s history, that of its Jewish community and that of your family to reconstruct the life of your grandfather. How did you go about the research, and how long did it take you to write the book?

I interviewed dozens of sources — from his business partners to community leaders, historians, diplomats, activists, experts on Iran and relatives of course.

My research took me to Ohio, California and Israel, where I conducted many of the interviews and found primary sources including personal letters, his last will testament and photographs. I had mounds of news articles, books, interview transcripts, FOIA [Freedom of Information Act] results. Everything is assiduously footnoted.

The book is layered with his story, as well as Iranian-Jewish, French Jewish, Iranian, and U.S.-Iranian history. As important are the themes of identity and belonging evoked within it.

The book took a decade from start to finish, but there were times when I had to step back from it because of the demands of work.

What are your personal memories of your grandfather?

Because I was in Iran only until the age of 5 and actually didn’t spend much time with him, I don’t have very many vivid memories of my grandfather, besides the time spent at his house.

How emotionally difficult was it to relive the events that led to your grandfather’s untimely death while researching and writing your book?

Since I was far away from those events at the time, I wasn’t reliving much.

As a news photo editor, I’ve seen numerous images of victims killed in conflict zones and natural disasters. Quickly after I started working at the Associated Press, I was on the war desk receiving photos from Iraq, many images too gruesome for broad public consumption.

No matter how harrowing the images, you can’t allow your feelings to get in the way of doing your job of telling the story.

What are your personal recollections of the trauma that ensued following the news of your grandfather’s execution? Did writing this book help you come to terms with your grief?

I was 7 when my grandfather was executed. I grew up knowing that an injustice was committed against him, and the book was to fulfill a promise to not forget. Gathering all the facts and putting it down on paper was the best thing to do.

How were you affected by the 2017 collapse of the Plasco building, Tehran’s first high-rise, built by your grandfather and his brothers in 1962?

A part of history was lost. I was sad to hear the news of the firefighters who lost their lives trying to put out the fire.

When I think of how [Ayatollah Ruhollah] Khomeini reviled Iran’s westernization and my grandfather in particular and see how many tall buildings there are in Tehran now, I can’t help but note the lack of vision.

What are the memories of your early life in Iran that you cherish the most? Do you hope to go back to Iran one day, if only to visit the tomb of your grandfather?

My best memories are with my maternal grandparents Mamanji and Babaji, and my mother’s family, since I spent so much more time with them at their house in Yousefabad.

We visit graves to honor the memory of the person, and my book does just that. I won’t return to Iran until it reckons with its long history of injustices. However, I want nothing more than for my father to visit his father’s grave in Beheshtieh and his mother’s in Damavand.