By Ahmad Rafat

Chiara Mezzalama has a special relationship with Iran: She moved there two years after the 1979 Revolution when her father, Francesco Mezzalama, became the Italian ambassador to Tehran. They lived in the embassy building located in the Farmaniyeh Garden, a princely estate located in an affluent part of north Tehran.

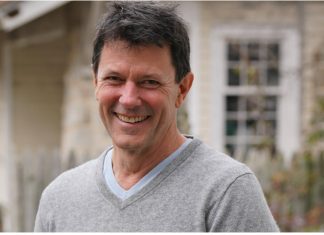

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Chiara-Mezzalama.jpg.webp” panorama=”off” credit=”Chiara Mezzalama. ” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

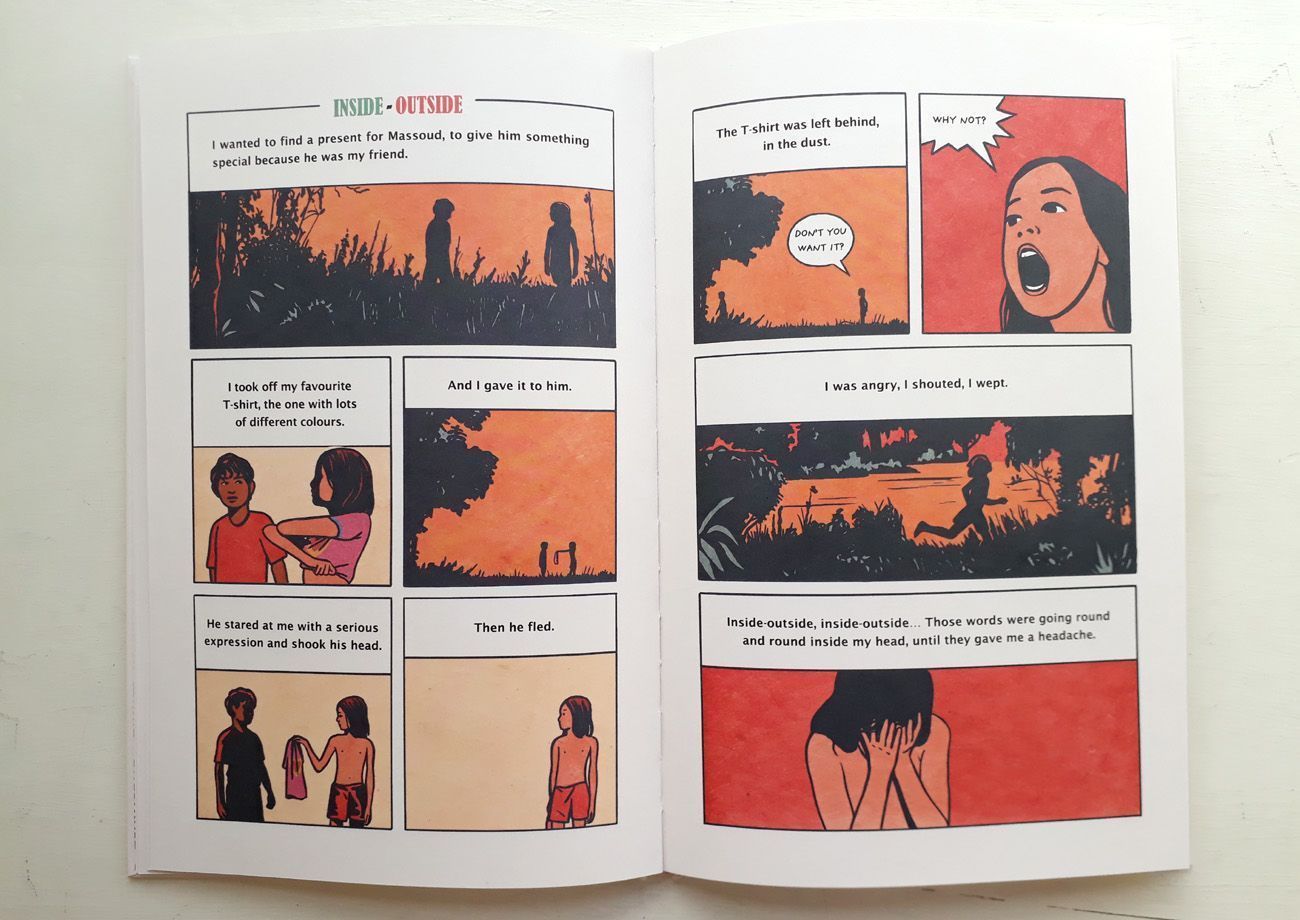

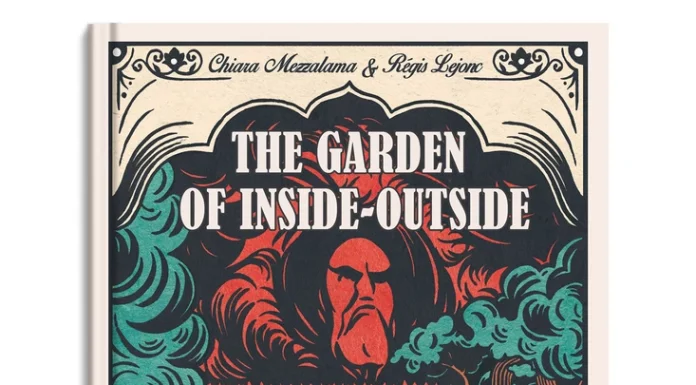

Mezzalama has now published a graphic novel about her experience. The original Italian edition of her book (Il Giardino Persiano) was published for adult readers in 2015. The English edition, written for children, was published in 2020. Last year, Newgen Publishing UK released the Persian-language edition, illustrated by the French artist Regis Lejonc.

Young Chiara’s stay in Iran coincided with a dark and difficult time in the country’s history. The Iran-Iraq war broke out a year before her arrival, and went on for eight years, causing the deaths of an estimated 500,000 people.

The book is the story of a friendship between two children: Chiara, a “prisoner” inside the embassy garden, and Massoud, an Iranian boy who scales the garden’s high walls like a cat, and brings news of the troubled outside world.

The Farmaniyeh Garden estate was built by Mohammad-Ali Ala ol-Saltaneh, Iran’s prime minister in 1913 and 1917, during the reign of the Qajar dynasty. The Garden’s first owner was the Qajar prince Abdol-Hossein Mirza Farmanfarma (1857-1939), who passed it on to his eldest son Firouz Nosrat-ed-Dowleh III.

Chiara Mezzalama, who now lives with her two children in Paris, spoke to Kayhan Life about her childhood memories of Tehran.

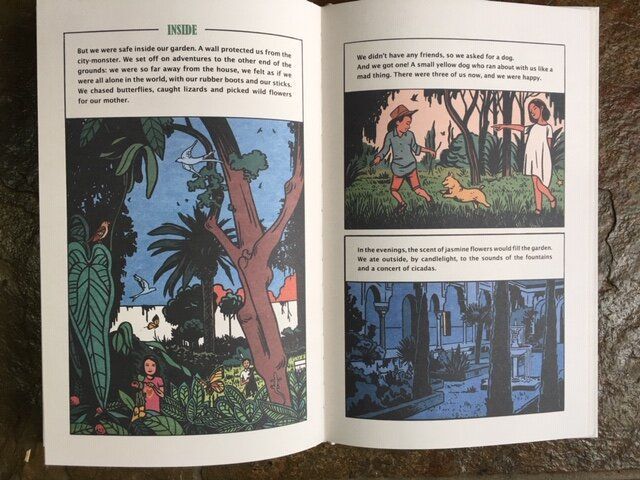

“The garden shielded me from the turmoil and war that raged outside its walls. It protected us children against the frightening events that occurred outside. The tall trees were like soldiers watching over us,” Mezzalama recalled. “I was only nine years old, and although our parents had prepared us for living in a country that was experiencing extraordinary events, I could not understand what was happening.”

Despite living in a beautiful and protected embassy compound, “we were acutely aware not only of the effects of the war but also of the ruling regime in the country,” Mezzalama explained.

“As an Italian, I could not understand why [Ayatollah Ruhollah] Khomeini’s pictures were plastered all over the city. Also, the regime’s influence on every aspect of people’s lives was incomprehensible to me, and the principal source of my anxiety, given that the war was taking place far away from Tehran. The garden and trees offered an alternative reality to the smell of blood and death that existed outside.”

Mezzalama’s only window on the outside world was her friendship with Massoud, a boy her own age who gave her a glimpse of what was happening outside the grand premises of the Farmaniyeh Garden.

“Massoud my answer to all the questions about the world outside,” she said. “The questions were mostly about a country that had undergone a revolution and was at war — vastly different from my home country, Italy. Massoud and I communicated on opposite sides of the wall with hand gestures: questions asked by a nine-year-old girl who did not understand most of the answers given by a boy her age.”

Although the Italian school in Tehran remained open, Mezzalama did not attend classes for safety and security reasons.

“The walls of the Farmaniyeh Garden deprived me of a chance to learn Farsi and get to know Iranian culture,” Mezzalama noted. “The memories of those years have stayed with me. So as an adult, I have tried to study Iranian culture. Living in another country for four years is a significant experience for a child. She becomes interested in the host country’s culture, whether consciously or unconsciously.”

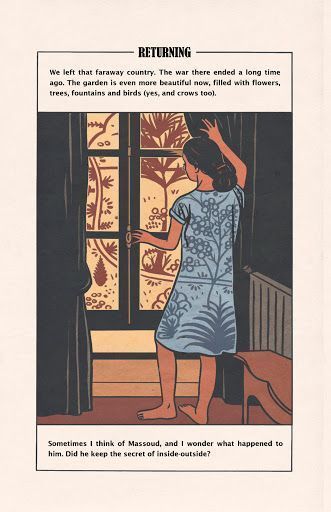

Mezzalama said she had wanted to visit Iran before writing the book, but worried that her experience of today’s Iran would affect her childhood memories.

“Today’s Iran undoubtedly differs from what a nine-year-old girl remembers,” Mezzalama noted. “There was talk of publishing the Farsi edition of my book in Iran, so I planned to travel to Tehran for the book’s release, but [the government] never issued a publication permit. Subsequently, I canceled my trip to Tehran because of safety and security concerns. Ultimately, the Farsi edition of the book was published outside Iran. I hope to travel to Iran one day so that I can merge my experience from one side of the wall with my observations on the other side.”

Asked what she took with her when she left Iran for Italy, Mezzalama said: “Fear of the police and anyone in uniform. Even now, I get very anxious when I go to a police station to renew my passport. I experienced this feeling in Iran for the first time, but it has stayed with me even after all these years.”

“I never think that people in uniform are there to help and protect me, but that they mean to harm me, and so I should hide from them,” she added.