Artists are regularly monitored and censored nowadays in places such as the Middle East and Asia. According to a new book by Farah Nayeri, they face complicated challenges in the West, too.

In “Takedown: Art and Power in the Digital Age,” the Iranian-born journalist describes how Western art has gone from being controlled by people at the top (kings, popes, dictators) to being questioned by people at the bottom.

Using social media platforms, ordinary voters, citizens and activists are urging the art and museum world to be less elitist and less male-dominated. They are also, in some cases, demanding that artworks be taken down and destroyed.

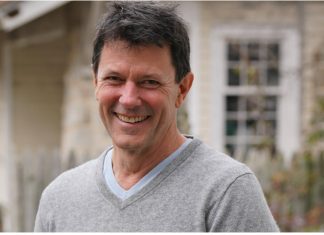

Nayeri — who is based in London and covers arts and culture for The New York Times — was born into a diplomatic family, and spent her formative years in the Middle East and North Africa. She moved to France in her early teens, and started her journalism career in Paris a few years later, initially as a reporter for Time Magazine, then as a contributor to The Wall Street Journal.

Nayeri subsequently became a correspondent of Bloomberg in Paris, Rome and London, covering politics and economics, then culture.

The book is published by the New York-based Astra House publishers. It is available online everywhere and in bookstores across North America.

Kayhan Life recently sat down with Nayeri for a conversation about her book.

Why did you decide to make your first book about art and politics?

My first book was supposed to be a memoir of my Iranian family. It’s an important project that I have already started on and that I intend to complete in the near future.

“Takedown” grew out of a New York Times article published in 2019, about an exhibition of the painter Paul Gauguin — who lived with very young girls on the island of Tahiti. The article focused on how Gauguin’s legacy was being reassessed in the age of #metoo. It went viral, and a New York agent reached out to see if I wanted to write a book on the subject of how art was being recontextualized in the 21st century.

How did you find the process of writing your first book?

I enjoyed the writing immensely — loved every minute of it. But it happened at a very difficult time in my life. Shortly after I signed a book deal with Astra House, a wonderful new publisher, I lost my father, Dr. Abbas Nayeri, a role model and a towering presence in my life. The joy of writing was fused with grief and pain.

Your book starts out by describing how art and artists were systematically censored throughout history. What motivated this censorship, and have those motivations changed today?

Art can have incredible power over human beings: a simple image can make someone happy, sad, angry, rebellious, aroused, etc. To prevent such emotions from being unleashed, people in power sought, for centuries, to control art and artists. Popes censored art to discourage promiscuity. Kings and dictators censored art to stay in power.

Today, in the Western world, democracy has given voice to the people, and the Internet has amplified that voice. So the art and museum world is facing demands to be more democratic, more representative, and less exclusionary. On occasion, it is coming under pressure to pull down certain works and even destroy them. So you might say that there is a new form of censorship: from the bottom up.

You write a lot about art. Are you a visual artist yourself?

Unfortunately not! Unlike so many fellow Iranians who have an innate gift for drawing, painting, and sculpture, I am completely incompetent in that department! Music is my lifelong passion; I play the piano and almost became a professional performer.

Do you ever cover Iran in your journalism and writing?

Occasionally. In the past few years, I have written a couple of pieces for The New York Times about Iranian artists, or about exhibitions of Iranian art. It’s always a pleasure for me to plunge back into my roots, to interview artists in Persian, and to learn more about our extraordinary culture and heritage. I take pride in the legacy of Iranian modern artists such as Leyly Matine-Daftari, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, and Bahman Mohasses. I am also interested in contemporary Iranian artists — those whose works I get to see in Europe, and those, living and working in Iran, whose works deserve to be much more widely exhibited abroad.

——

For more information about “Takedown: Art and Power in the Digital Age” by Farah Nayeri, please see the following link

“Takedown: Art and Power in the Digital Age”