By Ahmad Rafat

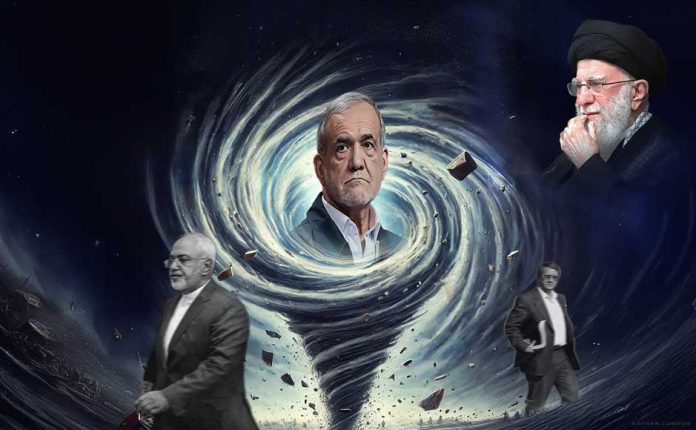

On March 1st, in the space of less than 24 hours, the government of Iranian President Massoud Pezeshkian lost two key figures: Mohammad Javad Zarif, the Vice President for Foreign Affairs, who resigned; and Abdolnaser Hemmati, the Minister of Economic Affairs and Finance, who was impeached by the Majlis (Iranian Parliament).

Zarif resigned after meeting Gholamhossein Mohseni Ejei, Iran’s chief justice, while Hemmati was ousted after serving 192 days in his ministerial role.

Iran’s President to Trump: I Will Not Negotiate, ‘Do Whatever the Hell You Want’

The removal of these two key figures is closely tied to a warning from US President Donald Trump regarding discussions on Iran’s missile program and regional activities. Trump has given Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, an ultimatum: either negotiate or face maximum sanctions, potentially leading to war.

The two individuals dismissed from Pezeshkian’s government were initially appointed to discuss negotiating with the United States. However, with Khamenei’s decision to avoid direct talks with the U.S., their roles became irrelevant to both the strategy of confrontation with the Trump administration and any attempts to engage with Washington under Moscow’s protection.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov reportedly called for Zarif’s removal during his recent visit to Iran.

Zarif’s well-known anti-Russian stance and his role as the architect of the 2015 Iran nuclear deal (the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA) are key factors in this request.

If negotiations were to resume with the support of Russian President Vladimir Putin, Zarif would not only be prevented from playing an active and constructive role — especially given his limited connections only to Democratic Party circles in the U.S. — but could also pose a significant obstacle.

During his 192 days in office, Hemmati, meanwhile, was unable to tackle Iran’s crushing economic challenges.

His strategy to resolve the country’s economic woes — such as strengthening the rial against the dollar and euro, curbing inflation, and preventing widespread poverty – hinged on securing an agreement with the U.S. to ease sanctions.

Additionally, Hemmati aimed to have Iran removed from the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) blacklist and restore the country’s banks to the global financial system.

FATF is an intergovernmental organization established in 1989 at the initiative of the G7 to develop policies to combat money laundering and the financing of terrorism

In February 2020, the FATF blacklisted Iran for failing to enact the Palermo Convention (the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime), the Financing of Terrorism (CFT), and Anti-Money Laundering (AML), blocking Iran from international banking system transactions.

Khamenei’s decision to reject negotiations with the U.S., which means the continuation of sanctions, created a conflict between Hemmati’s role in the government and the directives enforced on Pezeshkian’s administration from high up.

During Hemmati’s impeachment session in the Majlis, Pezeshkian openly remarked: “I believed we should engage in talks (with the U.S.), but the Esteemed Supreme Leader said we will not negotiate, so I declared that we will not negotiate, and that was the end of it.”