By Nazanine Nouri

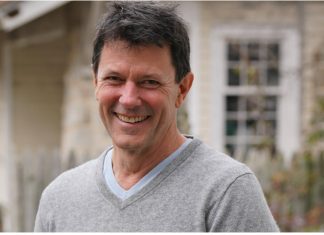

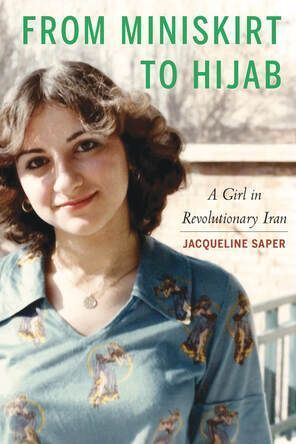

Jacqueline Saper is an Iranian-American author, speaker and lecturer based in Chicago whose memoir “From Miniskirt to Hijab: A Girl in Revolutionary Iran” won the Chicago Writers Association 2020 Book of the Year Award.

She moved to the US in 1987 and initially trained as a chartered accountant before taking up writing.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/JacquelineSaper.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Jacqueline Saper. ” align=”center” lightbox=”off” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

She addressed the issue of the compulsory hijab in a 2019 column published by the Seattle Times.

“Women in the United States are wearing hijab proudly to identify with their Muslim faith. However, while women in America wear hijab by choice, for the past 40 years, women in Iran are fighting for the choice not to wear one,” she wrote.

Kayhan Life caught up with Saper to find out more about her life and career.

What made you want to write this memoir, given the other memoirs about Iran that have been published in the U.S.?

My memoir is different because I am an unusual Iranian. As the daughter of an Iranian father and a British mother, I grew up in Tehran, with a hybrid identity. I was a do-rageh, the Farsi term for a person whose parents are from two distinct nationalities. I spoke fluent English and Farsi, and was able to cross between the West and Eastern cultures with ease. But I wasn’t just a regular dorageh. As a Jewish dorageh, in a predominantly Shia Muslim nation, I was a minority within a minority.

In my father’s generation, marrying across continents in the Jewish community was a practice that was unheard of and simply not done.

Your father decided not to leave Iran immediately after the Revolution. What led him to make that decision, and how do you feel about it as you look back on it today?

My father loved his native country, Iran. Even though he was educated at the University of Birmingham in England and had a British wife, he raised his family in Iran. My mother spent most of her career in American organizations. At one point, when I was a young child, my parents could have applied for a green card to emigrate to America. But my father wanted to contribute to the advancement of Iran.

My father taught metallurgy (the science of metallic elements) at the Elm-o-San’at University (Iran University of Science and Technology) and at the Tehran Polytechnic, the first established technical university in Iran. He was an optimist who believed that the Shah was invincible and would eventually restore the order. In his late 50s, at the time of the revolution, my father didn’t want to start a new life in a foreign country all over again. He knew that if he left property behind, most likely, they would confiscate it.

My father’s reasoning made little sense to me because the situation in the country was serious. Like everyone else in my community, I, too, wanted to get out of harm’s way. In his defense, everything happened so fast, and it was a confusing era.

You lived through important moments in post-revolutionary Iran – such as the U.S. hostage crisis. Can you recall how that crisis began, given that you lived near the U.S. embassy and witnessed it firsthand?

On November 4, 1979, the 27-acre United States Embassy in Iran was on Takht-e-Jamshid Street (Throne of King Jamshid) — renamed Ayatollah Taleghani Street after a 20th-century theologian — in a neighborhood of upscale stores. I was a newlywed and a block away, shopping for a gift for my husband. The embassy was huge, with red brick walls and a dark green iron fence. The American consulate always had long lines of people waiting, mostly to apply for US entry visas.

I saw the angry crowds gathering in front of the building. They threw their fists in the air shouting “Death to America.” From my past experience of living through the revolution, I knew something was not right. I was afraid of shooting, tear gas, or a stampede. I had three options. I thought of going into the shop and hiding in the back. The other option was to go toward the crowd to see what was going on. But I chose the third option and hailed an orange taxi, as there was still moving traffic on the side that I was on, and I got out of harm’s way.

That afternoon, my parents and I watched the footage on television. The radical Iranian students who called themselves “Students Following the Line of the Imam” had seized the embassy, now known as the “nest of espionage of the Great Satan.” The footage showed American embassy employees, handcuffed, and blindfolded, being dragged out of the building to a loud chorus of cheers.

Two weeks later, on television, I watched Ayatollah Khomeini give clemency to thirteen hostages: eight African American men and five white women. The Supreme Leader declared that the Islamic Republic was sympathetic to the plight of these two oppressed and discriminated groups of America. Another 52 Americans were kept as hostages for 444 days.

What was it like living as a young woman in Iran right after the Revolution? And how about for your young daughter?

Because of my age and where I was at certain times, many of the new laws directly affected my life. I studied for eight months for the university entrance exam known as the konkoor [concours], but then the new regime closed all higher education for three years. Once it opened, it became impossible for me to pursue any higher education.

The book reveals how I gradually lost many of my personal freedoms. Seemingly overnight, I went from living a carefree life of wearing miniskirts and attending high school to listening to fanatic diatribes, being forced to wear the hijab, and hiding in the basement as Iraqi bombs fell over the city.

When my daughter entered first grade at the age of six, she had to wear the full hijab. In a chapter of the book, I explain how she was quickly indoctrinated into embracing fundamentalist beliefs.

You wrote a powerful column about the compulsory hijab in 2019. What are your feelings about it today, given the social-media campaigns that have emerged in the past few years, and the election of a hardline president?

Women make fashion choices to express their identity and culture. Today, many Iranian women live in a country that dictates a dress code which does not align with their beliefs about what they should wear. I grew up unveiled in pre-revolutionary Iran, and later I wore a mandatory hijab for eight years while living in the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Today, some women oppose Iran’s forced dress code by pushing the boundaries of what is acceptable under the law. They protest the hijab as a symbol of their defiance in much the same way they did in 1979 when the decree was issued. Some have removed their headscarves and waved them around on sticks for passersby to see, and use social media to spread their message. The election of a new hardline president could impact a range of issues, including women’s rights.

Regardless of one’s opinion on hijab, as an Iranian American woman who has lived in both Iran and America, I know there is a huge difference between wearing hijab in democratic versus undemocratic nations.

Iranians now living in the West have a dual identity and are sometimes unsure of what culture they belong to. Your identity is even more complex, as you are also Jewish and half English. Have those multiple identities been enriching or challenging or both?

My parents spoke together in English. My mother never mastered Farsi, and her knowledge of the language was rudimentary. I constantly helped my mother by translating words and explaining cultural nuances. My hobby as a child was to take books and translate them from one language to the other. Within our family, we communicate by using the vocabulary of both languages.

Until the revolution, I spent every summer with my maternal relatives in England. I learned to switch my demeanor, behavior, and speech patterns according to who I was with. I had the gift of connecting with people from a broad spectrum. In Farsi, do-rageh literally means having two veins and refers to a person from two distinct heritages. I could also be categorized as a serageh, meaning three cultures, because America is the third culture that I embrace.

I use my language skills to volunteer as a translator and interpreter for the National Immigrant Justice Center. I work with supervising attorneys on behalf of immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. It’s so important to translate correctly: You must understand the culture to convey it properly to a person from another culture.

Currently, I’m working on my second book. Set in the backdrop of post-World War II Britain and Imperial Iran, it will be based on the true story of my parents’ unusual union of seventy years ago. The couple struggles to reconcile their differences by rising above the impediments of social prejudice, tradition, and politics. I will also incorporate the contentious dispute between the two nations, culminating in the 1953 coup d’état in Iran.

Have you gone back to Iran since the Revolution, and how do you react to events there from afar? Are you optimistic about the country’s future and your ability to return?

I haven’t returned to Iran since my departure. I hope one day to return to Iran, the country of my youth; the country that provided me with the foundation of who I am today. I follow Iranian news and politics in the Farsi and English language press.

Iran needs to elect leaders that will create reforms to benefit the people and return Iran to a more free, modern society.

For more information visit www.jacquelinesaper.com.