By Cyrus Kadivar

Dr. Amir Aslan Afshar, who died on February 18 in Nice, France, was one of the most interesting personalities I came to know in the Iranian diaspora. He was also a treasure trove for any budding historian in search of firsthand accounts of a bygone Iran.

Born in Tehran on 21 November, 1919, into a family that descended from the illustrious Afshar clan, Amir Aslan was the eldest son of Amir Masud, a colonel in Reza Khan’s army, and his wife, Amir Banoo. Educated in Tehran, Berlin, and Vienna in the 1930s and 1940s, he gained a doctorate in political science. He was fluent in Persian, German, English, Turkish and French.

Joining the Iranian Foreign Service immediately after World War II, Aslan Afshar spent 30 years representing his country on numerous diplomatic missions and as ambassador, until the late 1970s, when he entered the Imperial Court.

He belonged to a generation that rose to prominence during the Pahlavi era, and that was often unjustly maligned by Western critics and opponents — a generation that emphasized duty to country and sovereign above all else. It was these qualities that made Dr. Afshar excel as Chief of Imperial Protocol, a role that he fulfilled until Mohammed Reza Shah’s overthrow in 1979.

Away from his homeland, he retained great dignity. Settling in France, he was loved and respected by the dwindling Iranian exiled community who, like the White Russians before them, had journeyed to the Côte d’Azur for their vacations, then made it their permanent home after being chased out by revolution.

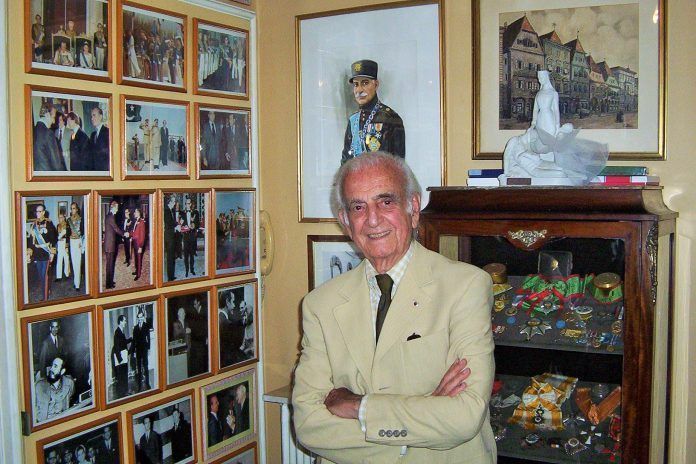

Dr. Afshar, a wise, self-effacing man with a sense of humor, was a pillar of the émigré Persian community, and a standard-bearer of enduring national pride. He enjoyed receiving guests, especially younger ones, at his residence. He loved showing his photo gallery and the collection of medals and awards that he kept in a vitrine for all to see and admire.

By the time he left this world, he had achieved the status of a grand seigneur, tirelessly reminiscing about his youth, his career, and the state of his beloved country. His passing leaves his family and his many friends and colleagues in mourning.

When I was given the heartbreaking news, I spent the day in my study remembering him. Once my tears had dried, I began to cast my mind back to my first encounter with him some 14 years ago. I was in my mid-40s, on a quest to track down the last eyewitnesses to the demise of the once-mighty Pahlavi dynasty.

At the time, Mr. Abdolreza Ansari — another exiled personality I had interviewed in Paris, who recently left us — kindly connected us, and I flew with my wife to Nice to hear Amir Aslan Afshar’s account of a shattered world for a book that I was writing. That was in early May 2007.

An Outstanding Iranian Statesman: Remembering Mr. Abdolreza Ansari

I headed to the iconic Hotel Negresco, a couple of blocks from his and his wife Camilla’s home. I walked through the marble lobby and into one of the luxurious Belle Époque ballrooms with its draperies, chandeliers, and large windows. Amir Aslan Afshar was already in his late 80’s. Yet he was unusually sprightly and alert for a man of his age. From the start, this tall, patrician-looking man impressed me with his charm, politeness, and refinement. Dressed in his beige suit and brown shoes, he wore the Patek Philippe watch that the last Shah had given him as a gift for his loyalty.

There was something deeply touching about him. In a sometimes melancholy tone, he evoked a forgotten world that had once seemed glorious, promising, and invincible. As with all of the prominent Iranian exiles that I had met, he was haunted by the Revolution, which cast a shadow over everything.

There was so much that he wanted to share. I was eager to hear it, but it was almost lunchtime and, after an hour of chatting, Amir Aslan Afshar proposed that we take a break and continue over afternoon tea.

Later that day, my wife and I arrived at his top-floor apartment on the Promenade des Anglais facing the sea. The former Chief of Protocol welcomed us in, and we entered a museum-like home that seemed a microcosm of his former life. The apartment was filled with antique furniture, books, old portraits, silk carpets, gilt mirrors, vases, crystal candelabras, and vintage objects.

On a wall near the library hung a curved sword dating back to Nader Shah Afshar. There was even a portrait of Asghar Khan, a distant ancestor who had served as Fath Ali Shah Qajar’s ambassador to the court of Napoleon, a portrait that Amir Aslan Afshar had purchased in a flea market in Nice.

On the desk where our host often sat working on his long-delayed memoirs was an antique French lamp, a small royal flag of Iran, and a telephone. It was a perfect setting for a man who had once lived in an insular universe of privilege and power.

Amir Aslan Afshar threw a loving glance at his elegant wife, Camilla, who was seated on a sofa beneath a large oil painting. Camilla was by then accustomed to her husband’s endless stream of visitors.

As the housekeeper brought tea and cake, Aslan spoke of his life. His wife listened patiently, even if she had heard the tales many times before, and sometimes interrupted him to bring her own memories of life at court. “We had such happy times,” she said.

She then picked up her leather-bound photo albums. “They are my most precious belongings, which I smuggled out of the country when I left Tehran a few days before my husband’s departure,” Camilla told us, as we gathered around a low table.

We flipped eagerly through the albums. Each photograph spoke of the glamorous era that they lived through. There were images of their engagement, wedding, home, and family. There were photographs of a cosmopolitan elite with connections to the Imperial Court, and of Tehran’s high society.

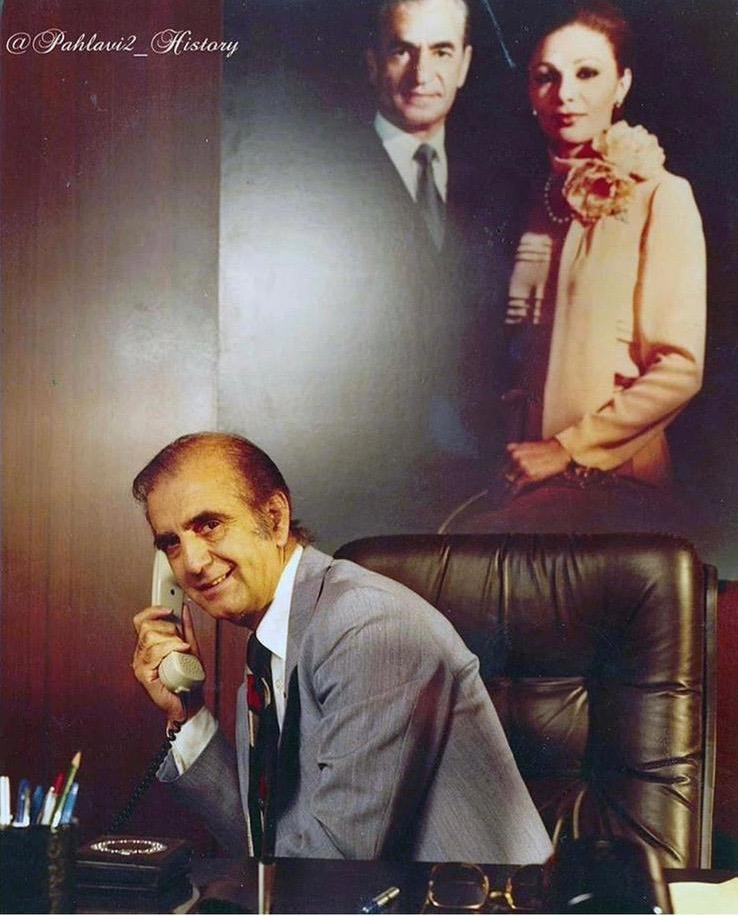

Elsewhere, Amir Aslan Afshar could be seen at the apogee of his career, when he was Iran’s ambassador to Vienna, Mexico City, Washington, and Bonn. Often the couple were pictured together.

“Those were marvelous days,” said Camilla, recalling the embassy parties, the champagne receptions, and the ballroom dancing.

As our wives engaged in conversation, Aslan Afshar pulled me aside to a square-shaped hall. Behind the dining area, he pointed to a photo gallery on the walls, testimony to a brilliant, prestigious diplomatic career. There were pictures of world leaders and important military and civilian personalities under the monarchy.

“When, in the summer of 1977, His Majesty appointed me Grand Master of Ceremonies of the Imperial Court, I was delighted,” he said. “It was a dream job working with the Shah and [Prime Minister Amir Abbas] Hoveyda, who was my direct boss.”

A whirl of diplomatic trips and visits by heads of state kept him so busy that he failed to see the dark clouds gathering on the horizon. “Political events took us completely by surprise,’’ he said.

Dr. Afshar then gave me a glimpse of those final days. By December 1978, after months of rioting, strikes and demonstrations, the army and government had lost control, with the mob clamoring for the king’s head outside the gates of Niavaran Palace.

“Some people once close to the Shah began to jump ship,” Aslan Afshar told me.

Despite facing death threats, Amir Aslan Afshar went to the palace every morning, working until night. It was there that he witnessed the end of the Shah’s rule, and the unravelling of the monarchy which he himself continued to serve. “Every day, top generals, cabinet ministers and foreign ambassadors came to advise His Majesty to crack down or initiate more reforms, but it was pointless,” Dr. Afshar recalled.

When a tearful Mohammad Reza Shah flew out of the country in January 1979, he took Amir Aslan Afshar with him alongside Empress Farah and a small entourage that included bodyguards, a valet and the palace cook.

Eighteen months later, after flying from country to country in search of a refuge, the Shah moved to Egypt. “Two days before His Majesty died, I visited him in a Cairo hospital,” Dr. Afshar recalled. The Shah was convinced that he had done his best and remained puzzled as to why his people had turned on him.

When President Sadat ordered a grand military funeral for the Shah of Iran, he instructed his chief of protocol to seek advice from Aslan Afshar, who ensured that the ceremony followed the appropriate protocol. It was to be Dr. Afshar’s last official role. He was present when the Shah was laid to rest at the Al Rifa’i Mosque in Cairo.

I returned to Nice on several other occasions and spent many long hours with Amir Aslan Afshar, reviewing his life and going over the past.

On my last visit in 2009, we recorded more than 24 hours of interviews. His sharp intellect was staggering. He never missed a beat. We both felt the urgency to record his memories for posterity.

Reliving the past heightened his sorrow. “Only a Shakespeare or a Ferdowsi could describe the tragedy that befell us,” he lamented. The horrors and atrocities that had destroyed our country, and the flight of three million Iranians across the globe, filled him with sadness.

Yet there were also moments of repose. Each time we strolled down the shaded boulevard for a coffee or lunch, a waiter or restaurant owner would greet Aslan Afshar with a hearty ‘Bonjour Monsieur l’Ambassadeur’ or ‘Votre Excellence’ as they handed him a menu.

Often, during our breaks, Aslan Afshar would read me Hafez poems from a small book he always kept in his pocket. It was, he said, “the best form of therapy” for him.

Sometimes his friends dropped in, bringing their own stories. He always gave me the afternoon off so that he could rest.

On my last night in Nice, we dined at a restaurant near his apartment. Camilla joined us, looking beautiful in the candlelight, and entertaining us with her presence, her jokes, and the tales of her golden years.

Not long before Camilla passed away — at her insistence and that of their daughter Fati — Amir Aslan published his memoirs in 2012 in the form of conversations with the scholar Ali Mirfetros.

In the years that followed, despite life’s hardships, Aslan Afshar never gave up on life or his determination to keep alive the old Iran. Always lucid, always on the ball, he gave countless newspaper, radio, and television interviews.

He never turned anyone down. He believed that every generation owed it to the next to pass on what they had experienced and witnessed, without exaggeration. I shared those sentiments in the introduction to my own memoirs, published in 2017.

From London, I posted Amir Aslan Afshar a signed copy of the book that had taken so many years to write. He called me from France to congratulate me, and as we spoke in what were his twilight years, he admitted that he had never expected his exile to stretch for decades.

His eyesight began to fade, but not his mind. I last spoke to him a year ago. Despite the pandemic ravaging the world, he expressed amusement at having turned into something of a celebrity on the Iranian émigré television networks. “At my age, I should be enjoying my retirement,” he laughed. “Instead, I’m busier than I ever was, which is probably a good thing.”

Until he drew his last breath, Aslan Afshar, a man who had lived to be more than 100, and who had witnessed the great calamities of the 20th and 21st centuries, never lost his zest for knowledge. He was halfway into writing a study about international diplomacy, a project that excited him.

He had just completed an eight-hour interview with an Iranian journalist in Nice when he was diagnosed with Covid-19. He died six days later at home, surrounded by his memories, with his loving daughter Fati beside him.

As I end this tribute, I am reminded of a scene which has never left me. I was at Nice train station about to head back to Paris after one of my trips. Amir Aslan Afshar had insisted on seeing me off.

We were feeling melancholic. The weather was overcast, and it was drizzling. As the train approached, Dr. Afshar handed me some lavender. “Something to remember me by,” he said. He winked, eyes sparkling. “They say it brings one luck on a long journey.”

Kissing each other on the cheek, as Persians often do, we said our goodbyes. Once on board, I looked out the large window. He was still standing on the platform in his raincoat, smiling. We waved at each other as the train pulled away, until he had disappeared from view.

Rest in Peace, Amir Aslan Afshar. Your memory lives on.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Amir-Aslan-Afshar-3.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Kayhan Life” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

What a beautiful tribute to Ambassador Afshar. One of the last remnants of Iran’s Belle Epoque has left us. We are richer for the memories he shared with you and you in turn shared with us.

Rest in eternal peace.