By Tim Cornwell

More than 20 works by leading Iranian artists have just gone on show at the British Museum as part of an exhibition celebrating its collection of modern and contemporary art from across the Middle East.

The exhibition, titled “Reflections,” comes as London’s museums open to visitors after many long months of pandemic-induced lockdown. It features works on paper by artists from across the region, mostly acquired by the museum since 2009, with a strong focus on Iranian work.

Venetia Porter, the British Museum’s curator of Islamic and contemporary Middle Eastern art said she did not know how the museum’s recent collecting from the region came to include so many Iranian works.

“It just kind of happened as the collection was built,” she said in an interview at the exhibition press opening. “I tend not to focus so much on where an artist is coming from or whether they are male or female, but whether the work excites me. It’s true that there is a lot of Iranian art in the collection.”

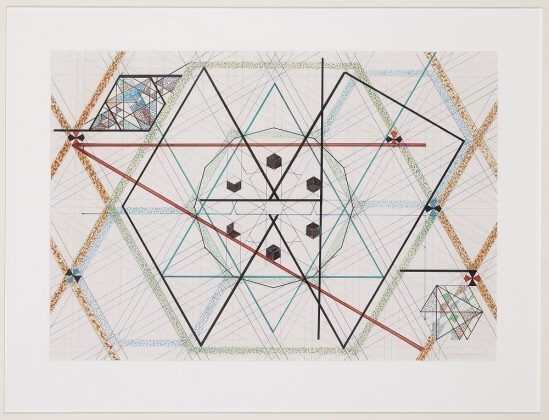

One possible explanation was the “consistency of vision,” she explained. “It’s really interesting when you look at the works by [the Iranian artists] Timo Nasseri, YZ Kami, Nazgol Ansarinia, Monir: that way of using Persian architecture to tell a very contemporary story.”

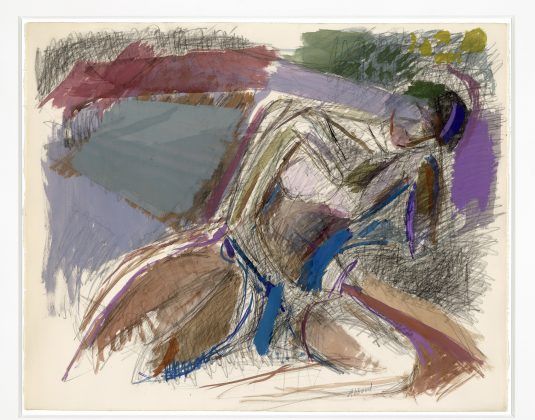

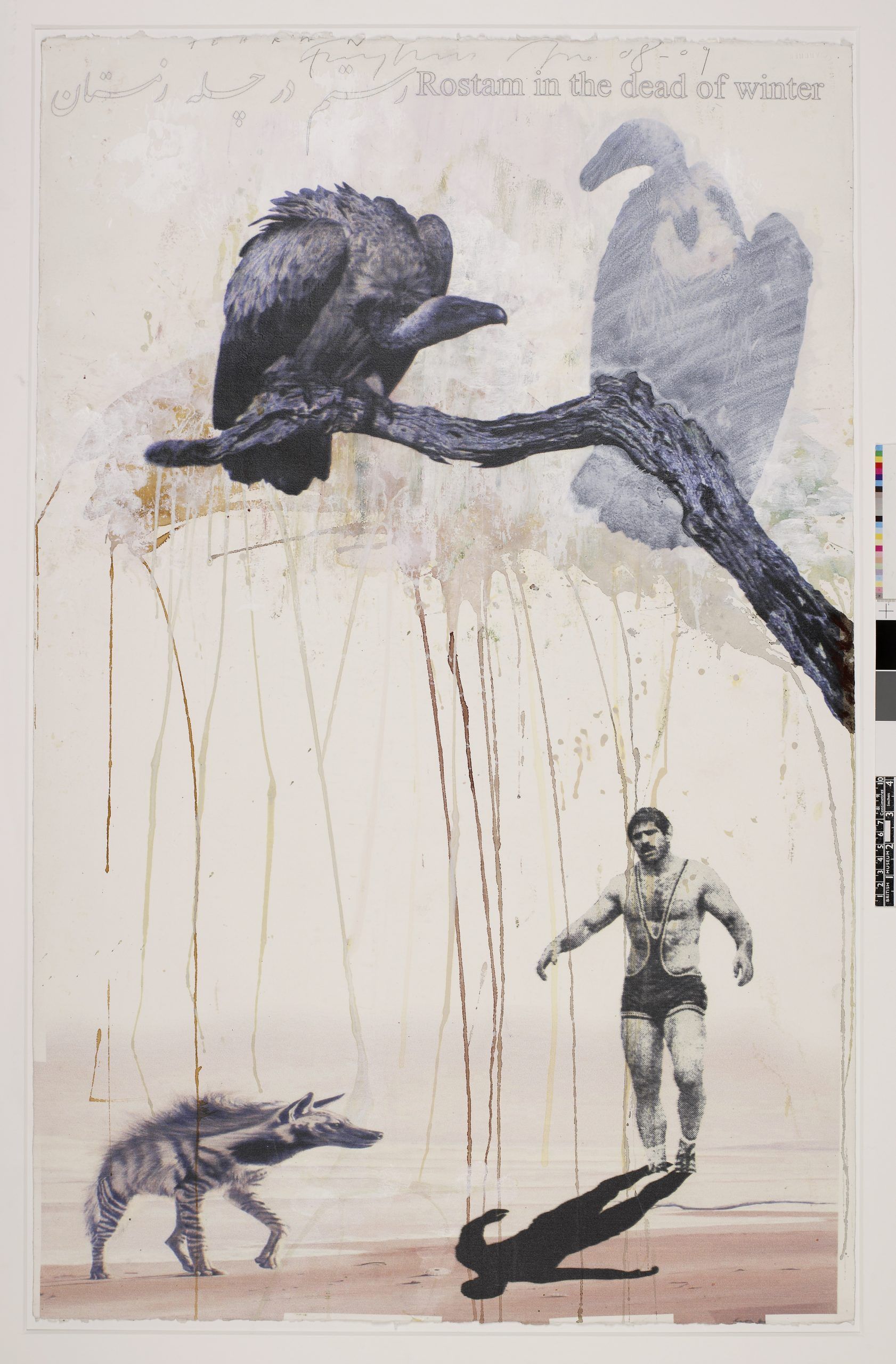

Stand-outs include Fereydoun Ave’s “Rostam in the Dead of Winter,” in which the epic hero of the Shahnameh, the “Book of Kings” epic poem by Ferdowsi, appears as a pahlavan, a wrestler, in a grim water-stained backdrop of vultures and hyenas.

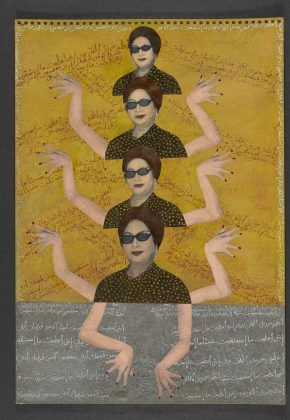

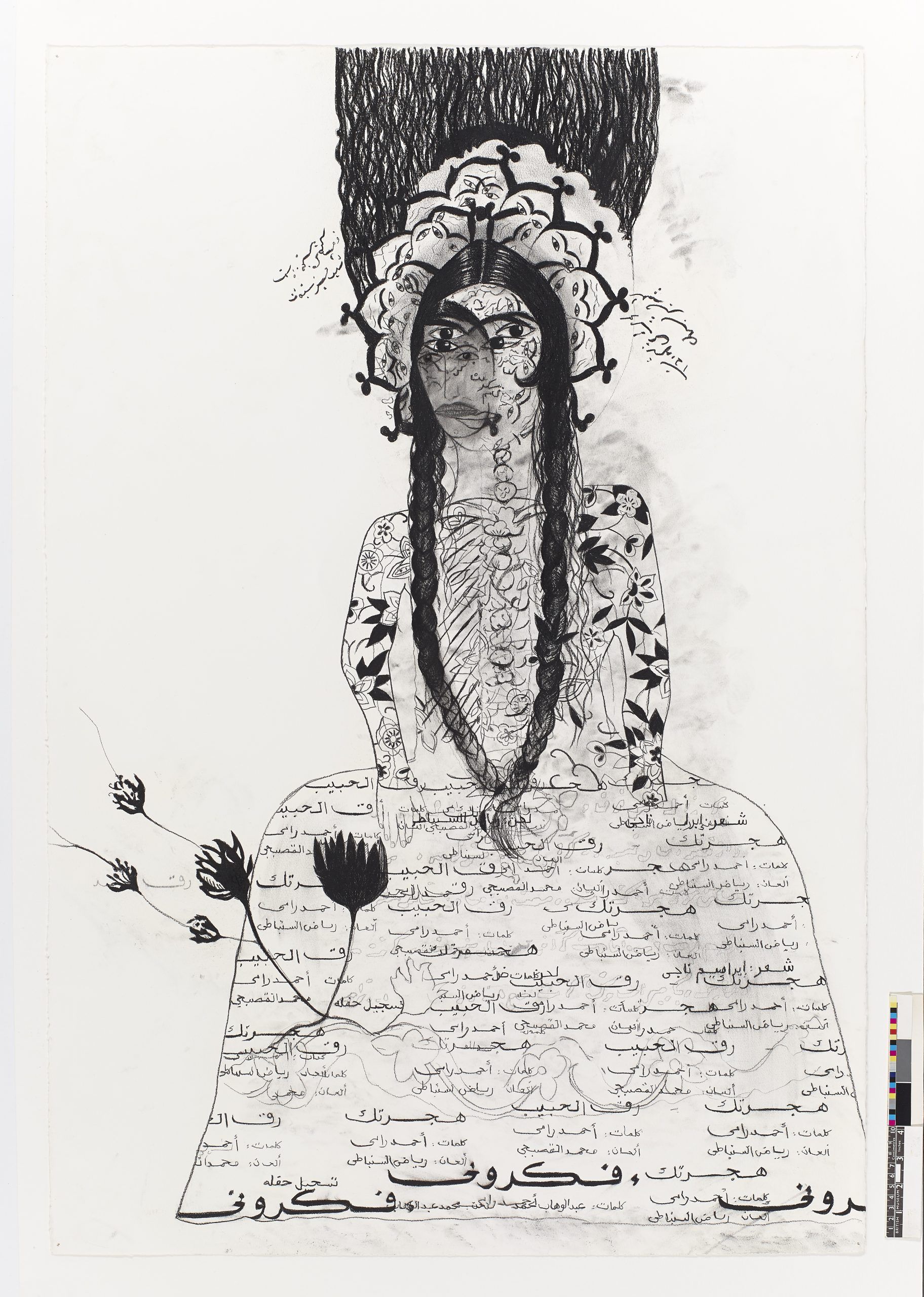

“Reflections” fills several large spaces in Room 90 of the British Museum, with works themed around the figure, abstraction, and the tangled histories of war and conflict. There is also a strong selection of women artists exploring the ‘female gaze.’ One such artist is Afsoon, who is famous for her works on paper, and who presents delicate woodcuts of objects from her childhood in Iran: a cassette tape, a bedside lamp, a transistor radio.

There are further displays on the other side of the building, in the Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic world (Rooms 42-43), which house many highlights of the BM’s Middle Eastern collections.

The exhibition reflects the role since 2009 of the museum’s Contemporary and Modern Middle Eastern Art acquisition group of patrons, who have come together to add new work from the region to its collection.

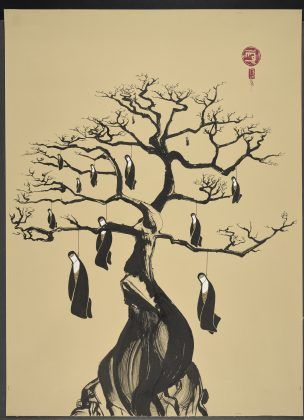

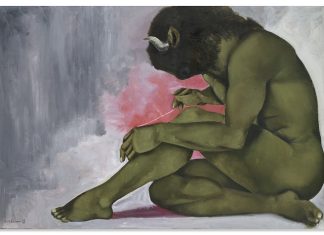

Fereydoun Ave’s take on Rostam is part of a selection of Iranian work relating to the Shahnameh and to Islamic literary traditions. It also includes an untitled work by Iman Raad showing armies clashing with each other as div, or demons, appear among them. These demons are often seen in Persian illustrations of ancient epics. The artist, inspired by Qajar-era lithographs, used a hand-carved stamp to create the piece.

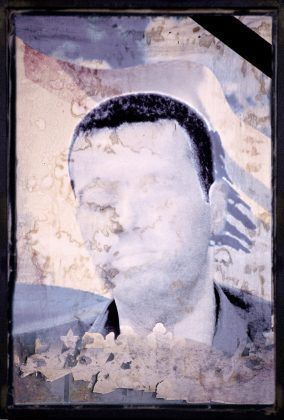

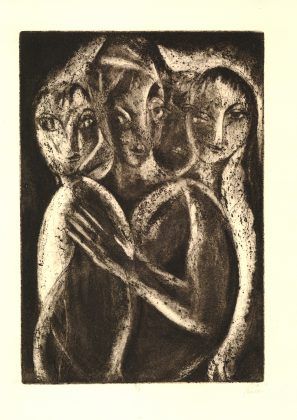

Works in the show, many acquired since the Arab spring, also come from Syria, Egypt and Tunisia. One unforgettable image from an Arab artist is Marwan’s Gesichtslandschaft (Face Landscape, 1973), a piece that transforms a face into a rugged landscape that seems to stare down the viewer from behind old hooded eyes.

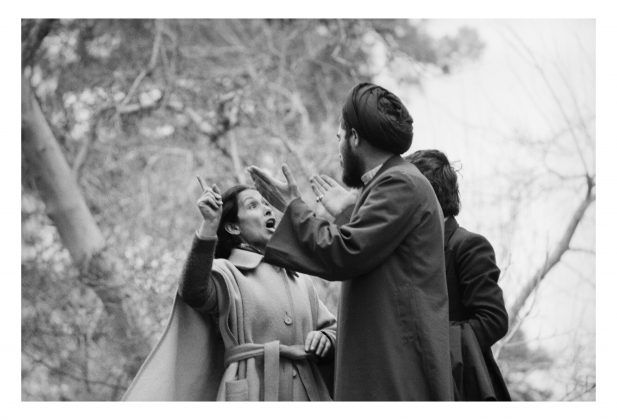

Greeting visitors at the door of “Reflections” is the painter Nicky Nodjoumi’s “The Accident” (2013), a floor-to-ceiling tableau of four suited men, one of them under questioning in a chair, the others gathered ominously around. Layered in its shading, with a crashed car as backdrop, it is spattered with paint: the artist works on his large pieces on the floor.

The Iranian artist, who lives and works in New York, often returns in his art to the experience of a four-month interrogation by the Savak secret police before the Iranian revolution.

What this opening work in the exhibition does not speak of is a cliched Middle Eastern setting, with mosques, minarets or veiled women.

“I was always keen to put it here first because it was so big,” Porter said. “I didn’t want people to think in any way that there was a stereotype, when you look at this you wouldn’t think Middle East.”

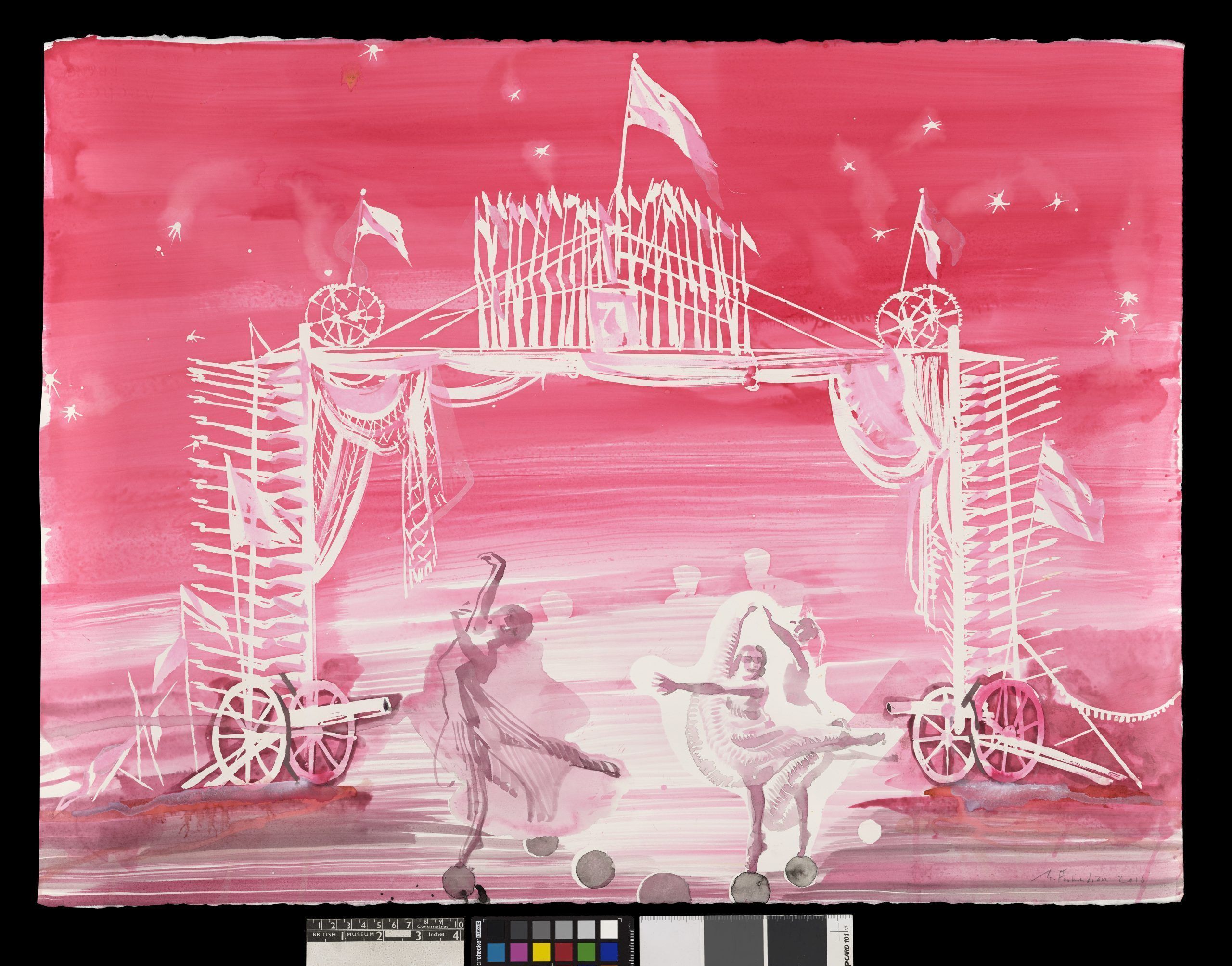

Another eccentric delight is Mehdi Farhadian’s quirky “Cannon and Ballerinas,” from 2018, where grinning ballerinas pirouette and spin against the pinky backdrop of canons and martial regalia around a triumphal arch, dancing in the face of war.

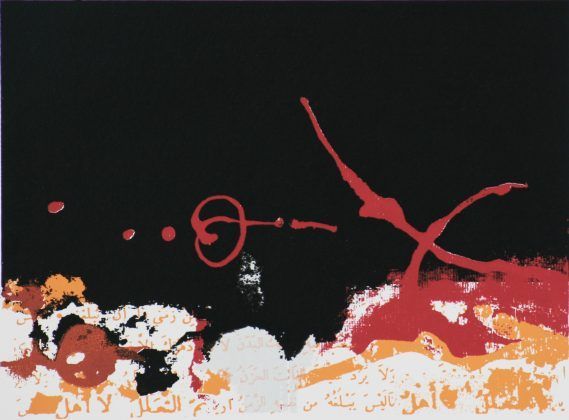

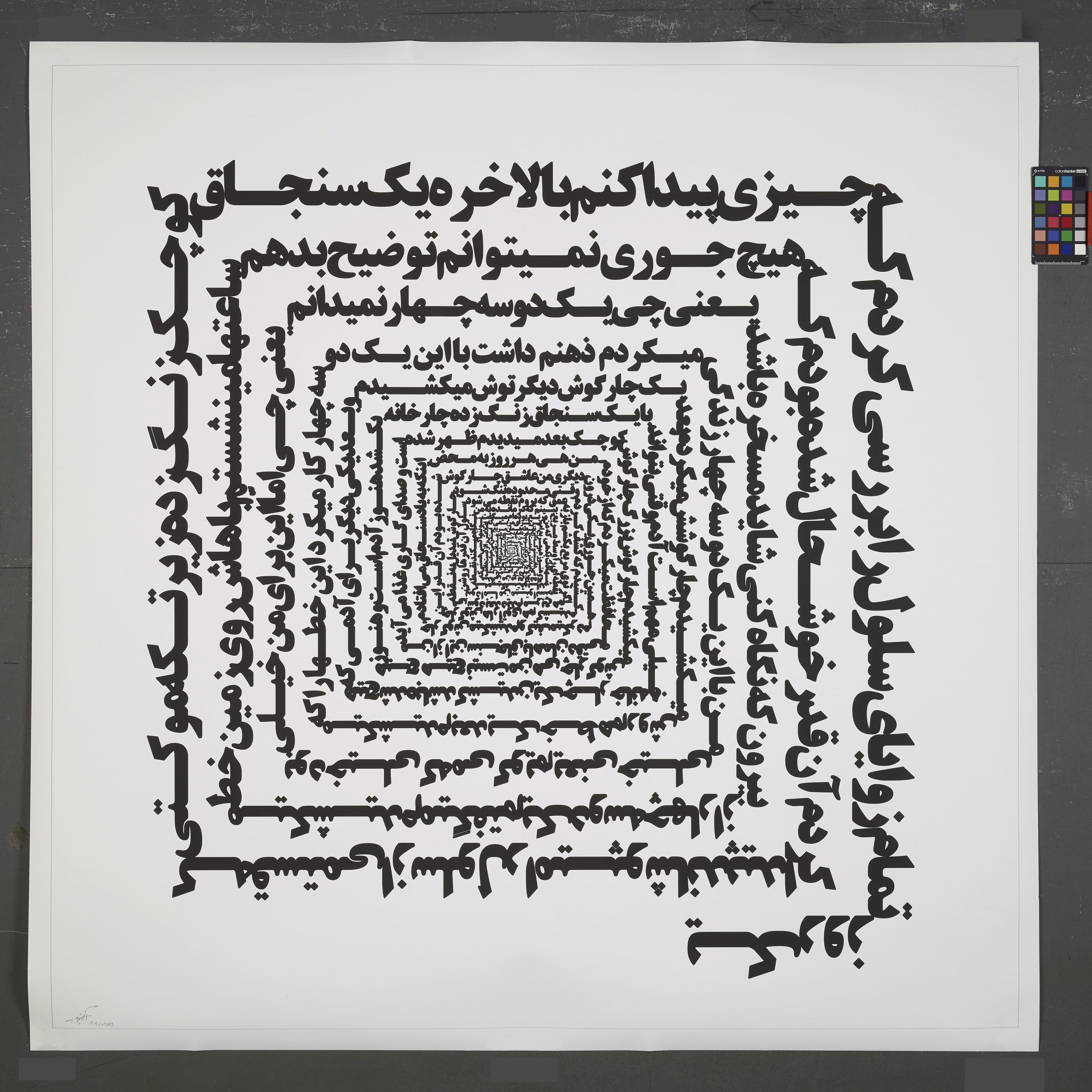

One of the most powerful pieces in the show is “Quod” (2010) by Barbad Golshiri, which uses shrinking black squares of Persian text in an explicit echo of Kazimir Malevich’s famous “Black Square.” The words are of A’ezam, a political prisoner in the Islamic Republic of Iran.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/18-05-2021-17.11.09-scaled.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”By Barbad Golshiri. ” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

“One day I looked around every corner of the cell…and then beneath the carpeting I found a rusted pin, my delight was boundless and I started to draw lines with it for hours,” reads the text. The squares seem to close around a prisoner as we look in.