By Ahmad Rafat

On June 28, Iran held an election to choose a successor for the late Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi, who died in a helicopter crash on May 19 while returning from a visit to the border area with the Republic of Azerbaijan.

The election marked a significant setback for Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, who hoped that a large voter turnout would give the Islamic Republic regime and the electoral process credibility.

According to official data from the Islamic Republic’s election headquarters, only 39.9 percent of the 61 million eligible voters went to the polls.

Some people believe the actual number of election participants could be significantly lower, possibly even a third of the reported number. Despite uncertainties and discrepancies surrounding the official figure, the election marked the lowest voter turnout in the Islamic Republic’s 45-year history.

In the 2009 presidential elections, 85 percent of the eligible voters turned out. In contrast, voter turnout in the 2021 presidential elections, which brought Raisi to power, was lower than in any previous ballot.

The most striking observation from the June 28 election is the unparalleled decrease in voter participation. Many eligible voters chose not to engage in the electoral process, showing a growing disillusionment and disengagement among Iranian citizens.

Also, placing a candidate from the reformist faction has historically shown no significant increase in voter turnout. This was evident in the 2009 Iranian presidential election, when reformist candidate and former Prime Minister Mir-Hossein Mousavi (in office from 1981 to 1989) competed against the incumbent, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

The 2009 election, which handed Ahmadinejad a second term in office, was marred by controversy. It sparked widespread accusations of electoral fraud, leading to mass protests across Iran and culminating in the “Green Movement.”

Khamenei and the think tanks within the Iranian establishment believed that introducing a reformist candidate following the widespread boycott of elections three years ago and the recent Majlis election in March of this year could inspire a significant portion of the population to vote.

However, according to official statistics, voter turnout fell below 24 percent in various cities, such as Tehran, Zahedan (in the southeastern province of Baluchistan), and Kurdish cities, such as Sanandaj and Mahabad.

According to official reports, no candidate secured over 50 percent of the votes, as required by law, leading to a runoff between Massoud Pezeshkian, who garnered 42.6 percent of the votes, and Saeed Jalili, with 38.8 percent of the votes.

Pezeshkian is aligned with the reformist and so-called moderate factions, while Jalili represents the extreme fundamentalist faction. The upcoming second round on July 5 will intensify the already polarized political atmosphere.

The supporters of Pezeshkian — which include many reformist and moderate political figures such as former presidents Mohammad Khatami and Hassan Rouhani, along with Javad Zarif, the foreign minister who served in two administrations under Rouhani — are rallying people to vote for him. They argue that supporting Pezeshkian is crucial to prevent a “Taliban-like” government from seizing power.

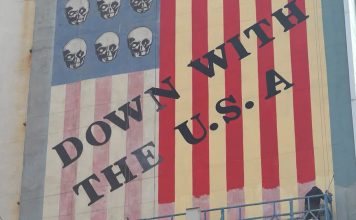

Supporters of Jalili are urging people to vote in the July 5 election using a similar approach. They argue that the nation should avoid falling into a trap set by the U.S. and the West. They also reference Khamenei’s statement on the election’s eve, which warned that “the elected candidate should not have ties to America.”

Today, Khamenei is confronted with a difficult decision: whether to select a successor who will uphold Raisi’s policies and establish a government that can bridge the gap between the leadership and the executive branch, fostering unity within the system.

Alternatively, he must consider whether handing over power to someone willing to engage in dialogue with the U.S. and the West is necessary for rescuing the Islamic Republic from economic and political isolation, especially considering potential conflicts such as a war between Israel and Lebanon’s Hezbollah.

It is unlikely that the election of either Pezeshkian or Jalili will significantly change domestic politics or resolve the current economic and social issues that Iranian society faces. Even if Pezeshkian wins on July 5th, challenges such as women’s freedom of dress and the improvement of living standards stemming from the influence of political mafia groups on Iran’s economy are expected to persist.

However, the election of these two candidates could spell distinctly differing regional policies and interactions with Western nations for the Islamic Republic.

The Iranian government that will take power after July 5 will need to consider not only the U.S. presidential elections in November, but also the recent appointments of Mark Rutte (the current Dutch Prime Minister) as the new head of NATO and Kaja Kallas (the current Estonian Prime Minister) as the successor to Josep Borrell as the European Union’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy.

Rutte and Kallas have been consistently critical of Russian President Vladimir Putin, particularly about the ongoing conflict in Ukraine. Both leaders have raised alarms regarding Iran’s nuclear activities and the supply of drones and other weaponry to Russia for the conflict.

The upcoming elections and the formation of a new government must address the evolving global landscape. The Islamic Republic must decide between two options by July 5.

Electing Jalili would align Iran with a path he previously spearheaded while leading the Supreme National Security Council and nuclear negotiations under former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s in office (from 2005 to 2013). This period saw the passing of three UN Security Council resolutions, notably Resolution 1929 in June 2010, which imposed extensive sanctions on Iran because of its nuclear activities.

Jalili’s actions had created conditions that could have led to a UN military intervention under Chapter Seven of the UN Charter, which empowers the UN Security Council to take “Action concerning Threats to the Peace, Breaches of the Peace, and Acts of Aggression (Articles 39-51).”

The potential outcome of Jalili being elected as president amidst the escalating crisis in the Middle East following the Hamas terrorist attack on Oct. 7 last year could be catastrophic.

If Khamenei’s recent strategy aims to ease tensions between Iran and the West, including the U.S., and prevent a potential escalation of conflict between Israel and Hezbollah, then Pezeshkian could be a suitable candidate to implement that policy.

Some argue that Mohammad Javad Zarif will be appointed as the foreign minister of such a government. Zarif succeeded Jalili in leading the nuclear negotiations and successfully concluded the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), also known as the Iran nuclear deal. Under Zarif’s leadership, many sanctions imposed during Jalili’s tenure as Iran’s nuclear negotiator were lifted.