At least six journalists working for the Iran International television network in the UK are at risk of harm from the Iranian regime, according to Adam Baillie, the spokesperson for the London-based network.

Incidents are evaluated by the UK’s counter-terrorism police and are deemed a concern if they pose a “credible threat to life.”

On March 29, Iran International TV presenter Pouria Zeraati was stabbed in the leg outside his home in London. The assailants boarded a plane at Heathrow airport and fled the country within hours of the attack. No arrests have yet been made.

UK Police Say Suspects Left Country Hours After Stabbing Iranian Journalist

The motive for the attack has not been confirmed, but a probe by UK counter-terrorism police is under way following ongoing threats made to the network by individuals believed to be connected to the regime.

“There are direct threats against certain individuals, the exact numbers of which we can’t say but certainly a good half dozen have received threats, including death threats,” Baillie told Kayhan Life.

“This then becomes dozens of Iran International reporters as far as families go, because they are harassed, rather than threatened. The families are just harassed continually, hauled in for increasingly aggressive questioning,” Baillie said. “They are told their family members shouldn’t continue working for the channel because it is a terrorist channel. That it is encouraging separatism, it is fomenting revolution and would result in the breakup of Iran, with the threat also that their family member would face legal sanction.”

Baillie said Zeraati had been subjected to threats by the Iranian regime “for a good 18 months” prior to the attack.

Zeraati, who returned to work on April 5, called the injury a “warning shot” in an April 6 interview with Sky news and added: “Whatever the motive was, the show must go on.”

Responding to the attack, the Islamic Republic’s most senior diplomat in the UK Mehdi Hosseini Matin, said on March 31 that Iran “denies any link” to the stabbing, in an interview with the weekly The Observer.

Iran’s government has regularly made threats against Iran International journalists.

Esmaeil Khatib, the head of Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence, said the outlet would not be safe and was a “terrorist network, and we take action against any terrorist act wherever and whenever we detect it,” in video footage posted Sept. 17 on X by Iran’s semi-official Fars news agency.

وزیر اطلاعات: رسانههای تروریستی در امان نخواهند بود. اینترنشنال شبکۀ تروریستی است و ما نسبت هر اقدام تروریستی هرجا و هر زمان تشخیص دهیم اقدام میکنیم. pic.twitter.com/6FYmNrgKtQ

— خبرگزاری فارس (@FarsNews_Agency) September 17, 2023

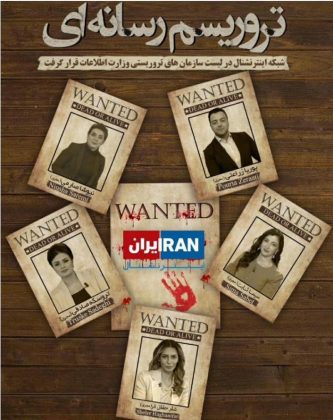

The Fars news agency also published posters in 2022 featuring the faces of several Iran International journalists including Zeraati, with the slogan “wanted dead or alive” under each picture.

The Fars news agency also published posters in 2022 featuring the faces of several Iran International journalists including Zeraati, with the slogan “wanted dead or alive” under each picture.

In that same year Hossein Salami, the head of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps warned Iran International journalists that “we’re coming for you,” while Mohammad-Taghi Naghdali, the secretary of the Islamic Republic parliament’s legal and judicial committee, called for the network to be shut down by placing pressure on Ofcom, the UK’s media regulator.

While the motive behind Zeraati’s attack has not been confirmed, journalists in the UK have been increasingly targeted by the Islamic Republic.

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) said in a statement about the Zeraati attack that threats against journalists escalated after the 2022 anti-government protests in Iran following the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini. “London is a particular hotspot for intimidation, because of the presence of major Persian-language broadcasters,” RSF said.

An internal survey of 96 BBC Persian employees produced in 2017 found that 44 members of staff had been accused of sexual indecency, while 86 reported being harassed. Almost half of those who filled out the survey said their parents had been interrogated by authorities in Iran.

Negin Shiraghaei, the founder of the London-based Azadi Network – a movement which advocates for gender equality and marginalized groups in Iran – is a former BBC World Service presenter and reporter. She was one of the first journalists in the UK to speak publicly about threats being made against reporters.

“For over a decade, many things happened to me and my colleagues at BBC Persian. But it took years for a corporation like the BBC to start taking action and campaigning against it because the mantra in those days was that as a journalist you shouldn’t become the story,” Shiraghaei said in an interview with Kayhan Life. “I might disagree with a lot of Pouria’s views, which he shares on his program, but the fact that someone who was brave enough to speak his mind is being targeted physically is unbelievable and it should be stopped.”

UK Unveils New Safety Measures for Journalists Targeted by Iran Regime

Shiraghaei first spoke out in 2010 after Iran officials targeted her family through home raids and interrogations.

While working at BBC Persian in 2017, Shiraghaei was blackmailed by Iran agents who threatened to publish revealing photos of her as part of a wider campaign against the outlet, which is seen by the regime as an arm of the British state.

Shiraghaei has also been subjected to threatening communications on Facebook and other social media platforms.

She has since given evidence twice to the United Nations Human Rights Council, including in June 2018, where she described incidents of online violence perpetrated against female journalists by the Islamic Republic.

“There are two stages in any revolution and the regime knows it. There is organizing and there is mobilizing. People are now being targeted because they’re seen as part of the mobilizing phase. That is scary for them because they know that everything inside Iran is at boiling point,” Shiraghaei said.

Despite a new action plan by the British government launched on Oct. 30 to provide more protections for journalists in the UK writing about Iran, reporters continue to face harassment and intimidation.

“We’ve had lots of members of staff at Iran International who have been stopped in the street by people. They have been located by these individuals and told ‘we know where you live.’ It’s insidious psychological warfare,” Baillie said.

“When the news about Pouria’s attack broke, I was getting a lot of messages from people and I could feel the fear of the journalistic community,” Shiraghaei said. “But I never heard anyone saying, ‘I’m not going to go in and not report on something or I’m going to stop doing what I’m doing.’ The community is just thinking about how we can protect each other how we can make sure friends and colleagues are safe.”