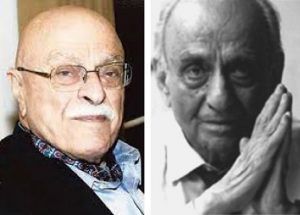

In the autumn of 1997, Sadreddin Elahi, a prominent Iranian journalist, interviewed the founder and managing editor of the Kayhan daily, Dr. Mostafa Mesbahzadeh. The interview covered a wide range of issues, including the history of Kayhan, and major political events that have shaped modern Iran.

Q: Kayhan’s reputation as a credible daily was established following the events of August 19, 1953 and the January 26, 1963 referendum. Subsequently, the paper also received the approval of the government. However, in some ways, Kayhan was more to the left of mainstream politics than its competitor, the daily Ettelaat. While some people described Kayhan as a left-leaning progressive paper, others went as far as suggesting that it provided a platform for the Tudeh Party (the Iranian communist party). What is your view on this?

A: You’ve raised two issues here. Kayhan didn’t become a left-leaning paper after the events of 1953 and 1963. It had been a progressive paper since its inception in 1941. The editorial in the first issue of Kayhan addressed every single article that was later included in the 1963 referendum (the White Revolution), including tackling illiteracy, dismantling feudalism, promoting women’s rights, and promoting profit-sharing schemes for workers. We had envisioned a 20-year plan to achieve these goals. Kayhan had to adopt a progressive political stance in order to promote these ideas. So the paper was a progressive and left-leaning publication from the start. I don’t mean partisan left, but nationalist left. Kayhan never aligned itself with a foreign power. Kayhan was the voice of the people, and that was the reason for its popularity.

The claims of Kayhan’s affiliation with the Tudeh Party started after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Prior to that, there was no indication that our editorial team had been infiltrated by the Tudeh party. Only on a few rare occasions did security forces arrest a handful of individuals who were suspected of having had ties to certain political groups. It was only at the height of the revolution that Islamists, leftists and members of the Tudeh Party emerged from within government organizations, national institutions and other establishments including Kayhan. By then no one could do anything.

Q: You launched the “National Resurrection Movement” [RASTAKHIZ] within Kayhan between 1959 and 1961. It was structured more like a political party than a cultural movement . You also set up a conference room where people from all walks of life could gather and air their grievances, which were subsequently reported in Kayhan the following day. You even commissioned theme music for the Resurrection Movement. There were rumors that you were going to be the next prime minister. How do you compare the National Resurrection Movement and the Resurrection Party of People of Iran, which was formed towards the end of the late Shah’s rule?

A: The National Resurrection Movement was created on the occasion of Kayhan’s 20th anniversary. The Resurrection Party of People of Iran, on the other hand, was a political entity. The Resurrection Movement adhered to the same principles outlined in the paper’s first ever issue. Its slogan was new ideas, a new path and a new Iran. People wore the movement’s badge, which depicted a map of Iran and the national flag. There were local branches of the movement which advanced the principles of the National Resurrection Movement. A local Resurrection center had a minimum of six members, which included a landowner, a rural resident, a merchant, a farmer, a teacher and a cleric. The local population elected the members.

The Resurrection Movement found enthusiastic support nationwide less than a year after its creation. I received a call one day from then Prime Minister Asadollah Alam (1962-64), who said: “The boss (meaning the Shah) has asked that you have an audience with him once a week.” During our first meeting, the Shah asked: “What is this Resurrection that everyone is speaking about? Who pays for all these marches, meetings, speeches and celebrations?” I replied: “people”. He said: “People? Ordinary people?” I said yes — everyday, ordinary people. The Shah paused and gave me a look of disbelief. To put his mind at ease, I suggested that he obtain a report on the movement. Meanwhile, he asked me for a copy of the Resurrection Movement’s charter.

After my first audience with the Shah, I found out that the Palace had asked the Ministry of Culture to forward all visual and audio recordings of the Resurrection meetings and marches that were held in Tehran and other provinces. It was apparent that the Shah was interested in learning more about the Resurrection Movement.

During one of my subsequent meetings with the Shah, he asked me if I’d been contacted by any foreign entities. I replied, “No, but they have reached out to us.” We had organized a dinner party for foreign ambassadors during which we showed films of the Resurrection Movement’s events. The guests were very impressed and wanted to see the films again.

Political circles gradually became aware of my weekly trip to the royal palace. Rumors started circulating about those meetings. Some even speculated that the Resurrection Movement was about to become a political party, and I was to be the next prime minister. Some even went as far as speculating about the composition of my cabinet.

Truth be told, I did have some political ambitions in the early days of Kayhan. I even entertained the idea of becoming a Majlis (Iranian Parliament) deputy and even a minister. However, as Kayhan grew, I gradually lost interest in public office. I even neglected to attend Majlis and later Senate sessions, and was routinely marked in the logs as absent without leave.

Kayhan eventually became the most prominent news and publishing group in the Middle East. Foreign reporters and journalists referred to the organization as the “Kayhan Empire.” At the time, Kayhan employed over a thousand people. It needed a full-time manager. I didn’t have the time to properly mange the Resurrection which by then had grown into a massive nationwide movement.

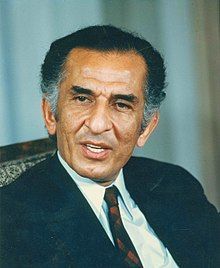

I set out to find a qualified individual who could take the helm of the Resurrection Movement. It was vital that the Shah knew and trusted the candidate. I consulted a few close friends among them a young former student of mine Mr. Qasem Lajevardi. He recommended Dr. Jamshid Amouzegar.

I welcomed the suggestion. Dr. Amouzegar was a young educated man from a prominent Iranian family. In my view, he was the right person for the job. I was also certain that the Shah would be receptive to the idea. Mr. Lajevardi agreed to speak to Dr. Amouzegar about this. Mr. Lajevardi arranged a meeting at his house where I could discuss the Resurrection Movement with Dr. Amouzegar.

I took all the film footage of the Resurrection events with me to the meeting at Mr. Lajevardi’s house. Three of us spoke for hours. Dr. Amouzegar was clearly impressed with the movement. They couldn’t believe that thousands of people would voluntarily organize and participate in these events.

Dr. Amouzegar wanted to know who was funding the movement. I told him that people were financing the events, and that the Resurrection Movement was not receiving any help from the government. Dr. Amouzegar was very surprised to hear that. Everyone wanted to know who was controlling the movement.

I didn’t hear back from Dr. Amouzegar after that meeting, but he praised the whole enterprise. As fate would have it, he joined the movement twelve years later of his own accord. Dr. Amouzegar later became the executive secretary of the Resurrection Party of People of Iran. In a relatively short time, he rose to the leadership of the progressive faction of the party before finally becoming its general secretary. Dr. Amouzegar eventually became the country’s prime minister. This is called destiny.

During my weekly audiences with the Shah, I would brief him on the Resurrection Movement’s activities including the duties of various centers and their interactions with each other. I would also answer his questions about Kayhan and other matters. The Shah wanted to know whether I or other organizations and individuals were in charge of the movement. Without addressing the issue directly, he aimed to assure himself that suspicious characters specially foreign entities were not pulling the strings behind the scenes.

The Palace would normally let me know in advance about the time and date of my next audience with the Shah. The weekly audiences, however, stopped after a while. I felt extremely privileged to have been able to hear the Shah’s views on the country’s affairs and explain the aim and mission of the Resurrection Movement to him during those meetings.

Prime Minister Alam and I had a lunch appointment one day. It was exactly a day before the new Prime Minister, Hassan Ali Mansour (appointed 1964 – assassinated in 1965) took office. Alam asked me to meet him at his house instead of the ministry building. Over lunch, he told me that I “had just missed the chance of becoming the next prime minister.” I told him that I didn’t know that I was being considered for the post. Alam said that the Shah was trying to decide between Mansour and myself. He said that was the reason for my weekly audience with the Shah.

I jokingly asked him about Shah’s reason for not selecting me. Alam said: “Your National Resurrection Movement is the reason for you being passed over for the job. You have launched a nationwide movement that has its own charter, slogan, theme song and flag, but there is no mention of the Shah anywhere in your movement. He is after all the founder of the (White) Revolution. One who wishes to become the country’s prime minister must respect the Shah and gain his favor. You completely ignore this point.”

Alam was both right and wrong. It was true that, in one way or another, the Shah’s name had to be included in any good and positive achievement in the country. One could have also argued that the Shah’s name should have been associated with social revolution and reforms that were being promoted by the Resurrection Movement. But if I had included the Shah’s name in our slogans, songs and charter, then people would have concluded that the movement had been created and financed by the government. They would have abandoned us. We wouldn’t have been able to hold large marches. Ultimately, people would have stopped all financial contributions. They might even have asked to be paid for their participation in the movement.

A few days after taking office, Prime Minister Mansour came to see me. He sought Kayhan’s cooperation with the government, arguing that the paper’s progressive politics and the National Resurrection Movement’s charter were completely in line with the principles of the White Revolution. He said that we should all work towards achieving our common goals. While assuring Prime Minister Mansour of our unequivocal cooperation with his government, I also reminded him that Kayhan had been working towards realizing those goals for 20 years.

I cited the editorial in the first issue of Kayhan as evidence of our initiative. I reiterated Kayhan’s commitment to the articles and spirit of Shah’s White Revolution. I pointed out that it was quite challenging to implement some of those progressive ideas 20 years earlier. In other words, it took that long for the revolution to bear fruit. I told the prime minister that he could depend on our cooperation. That made him very happy.

Mansour suggested that our continued collaboration could enable the progressive groups and the Resurrection Movement gain the majority in the next Majlis election. He also believed that members of those groups could occupy posts in the government as well. I thanked the prime minister, but insisted that the it was too soon for the Resurrection Movement to evolve into a political party. I gave a tour of Kayhan to the prime minister who had never been at the paper before. He saw the slogans and principles of the Resurrection Movement displayed and posted on the walls of the newspaper, particularly the following lines which he liked and wrote down:

O farmer, your fortune

is that of Resurrection

O worker, your hand and arm

are the friends of Resurrection

The National Resurrection Movement held its meetings in a large room which we used to host luncheons. It gradually became a conference room where our writers and reporters held meetings and conducted Interviews. Most visitors were government workers, community leaders, athletes, artists, cultural personalities and merchants. Kayhan’s conference room had been constructed before the creation of the National Resurrection Movement. We entertained close to 100 guests a day in the conference room.

Kayhan benefited from these daily interactions. Most guests were taken on a tour of our facility. They would naturally share their experience with friends and family. So it was a good public relations exercise for us. We also held lunch and dinner parties for domestic and foreign dignitaries who traveled to Tehran to attend seminars and conferences. They were shown film footage of the Resurrection Movement and were taken on a tour of the building. Guests would interact with the writers, journalists and staff, which created a warm and constructive environment.

Q: Did the Shah or any of his prime ministers ever consulted you about the issues facing the country or sought your view on selecting a minister?

A: During the early days of Kayhan, governments came and went, and for the most part, they left us alone. We, on the other hand, didn’t ignore them. We printed at least one or two articles in each issue of Kayhan criticizing the government. It wasn’t long before Kayhan became an influential and progressive political newspaper. The paper was being discussed in both right-wing and left-wing political circles. Our circulation rose rapidly.

Gradually, each new government sought our cooperation. We couldn’t give our unequivocal support to any government. Kayhan had its own goals and plans. We did embrace any government whose policies were in line with one of our objectives. However, Kayhan never hesitated to criticize the same government if its actions contradicted our principles. We also never gave our unqualified support to a prime minister. Conversely, no prime minister consulted us regarding the country’s affairs, or in relation to selecting ministers.

We had an entirely different relationship with the Shah. We were fully informed about his views. His objectives were also ours. We worked towards achieving those goals. If the Shah found a particular story, article or commentary objectionable, we would print a follow-up piece explaining our position and dispelling any misunderstandings. These instances were rather rare during the early years of Kayhan, but they occurred at a greater frequency in the later years. There were instances when certain programs contradicted time-tested traditions, the social and cultural framework and the wishes of religious leaders (for instance, land reform, women’s voting rights, and calendar changes).

Q: Would they give you advance notice about their plans and programs, or would you hear about them on the radio and through your reporters like everyone else?

A: It would be very unusual for us not to have prior knowledge of an upcoming announcement or event. We would be at fault on those rare occasions, for failing to stay on top of a story. I mentioned a few instances such as women’s voting rights and land reform. We couldn’t wait until those bills were ratified. They were at the top of Kayhan’s wish list. We were informed about their progress well in advance.

We, however, didn’t know anything about the plan to change the calendar, and found out about it through the printed news. We took a different position on the issue of changing the calendar than we had on the women’s voting rights and land reform. There were heated arguments over the issue within Kayhan, with those opposing the plan in the majority. We subsequently limited our coverage to merely reporting on the plan to change the calendar. We didn’t argue the point in the paper.

Q: You stated earlier that the Shah had financed Kayhan. What was his view of the paper towards the end of his reign? For instance, how did he, the government and the military react to Kayhan printing a full-page picture of Ayatollah Khomeini?

A: I remember it well. It was the final year of Prime Minister Amir Abbas Hoveyda in office (1965-77). I was summoned by the Shah one day. I knew something was wrong when I arrived at the Palace. The Shah looked angry. Without any warning, he asked: “How should we deal with Kayhan and your actions? All senior officials including the prime minister, security officials and governors all complain about you not printing important news.”

I immediately realized that some powers were conspiring against Kayhan behind the scenes. They were trying to change the Shah’s view of us. I asked the Shah if I could ask him a question. He angrily responded: “No one asks us questions, but go ahead.” I said: “Why do you choose Kayhan whenever you wish to make an important domestic and foreign issue known to the nation? Why do you summon Kayhan or Kayhan International to conduct important interviews with you?” the Shah replied: “Because these two newspapers have the largest circulation, and foreign news agencies and organizations use these two papers as their main sources of information about Iran.”

When I sensed that the Shah’s anger had subsided, I set out to explain to him why the country’s senior officials were maligning Kayhan. I explained to the Shah that those officials expected Kayhan to print and publish any news or photograph they sent us, something we simply couldn’t do. I said: “Kayhan wasn’t a mouthpiece for the government. It belonged to the people. We are for the Shah and the people. If we were to betray the people’s trust, the paper would lose its readership and had to shut down.”

I took advantage of my audience with the Shah to let him know that we anticipated that Kayhan’s circulation to reach the one million mark that year. The Shah was very kind and gracious to me. Prime Minister Hoveyda called me the next day and said: “You complained about us to the boss.”

As you well know, we accompany any major news with appropriate photographs. However, the news about Ayatollah Khomeini never included his photograph. I don’t know how this oversight occurred. The security agencies might have suggested that we shouldn’t print his picture. Meanwhile we knew that we would eventually had to publish his photograph in order to correct our mistake. We agreed with Ettelaat daily that both papers were to print Ayatollah Khomeini’s picture at the same time..

It was either 31 August or 1st September 1978 when I received a copy of Kayhan with Ayatollah Khomeini’s photograph featured prominently on the front page. What could have have happened to prompt this action, I thought to myself. I was in my office until 14:00 on that day, and no-one had mentioned anything about printing that photograph to me. I went to Kayhan to find out what had happened. There were a lot of rumors circulating around those days including one suggesting that the government was negotiating with Ayatollah Khomeini about his return to Iran. We’d apparently received a tip about a plane that had left for Baghdad, sparking speculations that it was to bring Khomeini back to Tehran.

Our reporter, Sharifemami, had gone to the ministry to collect more information about the rumor. He had run into the prime minister in the corridor and asked him if there was any truth in the rumor about a plane bringing Khomeini back from Baghdad. The prime minister had not replied to the question but only smiled. Our reporter had interpreted the smile as a “yes” and had rushed back to the paper with his so-called exclusive scoop. Kayhan had run the story generating a lot of commotion. The only bit of that story which was actually true was that a plane had indeed flown to Baghdad but to bring back a prisoner named, Ashuri, who had been implicated in the burning of the Rex Cinema in Abadan.

I’m certain that the Shah was extremely unhappy about Kayhan’s front page story. I tried to explain the situation to him as it had actually unfolded, but I’m not sure he believed me. The government and the military were also upset and angry. I took full responsibility for that incident and continue to do so to date. What I need to stress here is that, Kayhan had always remained faithful to the principles outlined in its first ever editorial. We believed Iran belonged to the Iranians. We envisioned a prosperous, free and independent Iran.

Now that we’ve come to the end of this interview, I think it is imperative that I should entrust you with two important documents for historical reasons and also for prosperity’s sake. The first one is the editorial in the first ever issue of Kayhan and the second one is the principles of the Resurrection Movement which was in fact the charter for this semi-official political movement.

Q: What was your role in determining Kayhan’s politics? Did you have a direct influence on Dr. Faramarzi’s famous editorials? Did the editors in various sections just listen to your ideas, actually implement them, or ignore them altogether?

A: In the beginning, I didn’t have any influence on the content, simply because I was new to the world of print journalism and politics. I knew what I wanted to achieve, but didn’t know the ins and outs of the trade. It took me months to gain any meaningful insights into this field. I was carrying a copy of the first Kayhan editorial in my pocket at all times. I had it with me everywhere I went. I read it over and over again. I even had it framed and hung in my office. Its premise and assertions are as true today as they were on the day they were written.

Truth be told, it was Dr. Faramarzi’s powerful writing and his incomparable intellect that gave Kayhan its strong start. I don’t know how things would have developed if he hadn’t been with us from day one. Every morning, we would compile the day’s news and give it to Dr. Faramarzi, who would sit in his office and write the daily editorial. People would wait all day with great anticipation to read his editorial in the afternoon paper. He and I never disagreed over the topic of the editorial. We worked really well together.

My relationship with other editors was different, of course. We always our differences over subject matter and content. I would go along with their decisions if they argued their positions convincingly. Otherwise, they would do it my way. However, these differences in opinions were so rare that I can’t even think of one instance that stands out in my mind.

Q: I’m sure you recall a children’s song which says: “It wasn’t me, it was my hand and the sleeve of my shirt.” Twenty years have passed since the Islamic Revolution. When asked who was responsible for that revolution, many of the former senior officials offer explanations that resemble that children’s song. They hold the Shah solely responsible for everything that occurred. What do you think?

A: As you said, that is a children’s song. If I were to write an adult version of that song in relation to what happened in Iran, it would say: “Who was it? Who was it? It was me, my hand and not the sleeve of my shirt!” We are all responsible for what happened. Blaming the Shah for everything is unfair and unconscionable, and shows a complete lack of understanding of the events on the part of those who espouse such irresponsible assertions.

In conclusion, I’d like to thank the Foundation for Iranian Studies and the Iran Nameh publication for their excellent work in recent years in studying, preserving and promoting the social, cultural and literary heritage of Iran.