By Ali Sharifian (Translation: Ramin Khanjani)

On a bone-chilling evening in Montreal, art lovers make their way to the Z Gallery for an event organized by Shahrzad Arzadi. The evening features a conversation with the photographer and filmmaker Aryan Arian.

While Aryan’s photographic work has been shown in solo and group exhibitions in Canada and Europe, most of his fans have come to know of his work via the Internet. “My Facebook page has been taken down four times after being reported,” says the artist in an interview with Kayhan London. “Now I’ve started designing a photoblog to showcase my work without restrictions.”

Aryan was born in Kerman, Iran to a religious and working-class family. At the age of seven, his father, who worked as a driver for a Kerman foundry, lost his life in an accident.

Seven years later, “I volunteered to go and fight on the frontlines of the Iran-Iraq war,” the artist recalls. “My personal experience led me to to take an unflinching stance against war, and in particular the recruitment and military exploitation of young adults.”

Aryan also “renounced religion at the age of seventeen,” he says. “I developed an interest in writing and photography and cinema.”

His first short film received the editing award from the Iranian Young Cinema Society. On the side, he wrote short and long stories and poems, “to overcome my solitude.”

As a young adult, he joined a theatre troupe run by Kanoon (The Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults) and acted in a few plays. After graduating from high school, he was admitted into the film programme of the Cinema and Theatre Faculty in Tehran, and received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in film directing. In 2001, he decided to make a documentary on Bahram Beiziai, the renowned Iranian playwright and filmmaker. He spent three months on the project; it remains unfinished.

Like many other artists, Aryan Arian could not stand the stifling environment of Iran and emigrated to Canada in 2000. It was there that he devoted himself seriously to his art practice. To update his skills, he went back to school and took a course on video editing.

Then, in 2004 – two years after his divorce – he “decided to make nude art the focus of my practice. From that time on, I have been taking nude photographs.”

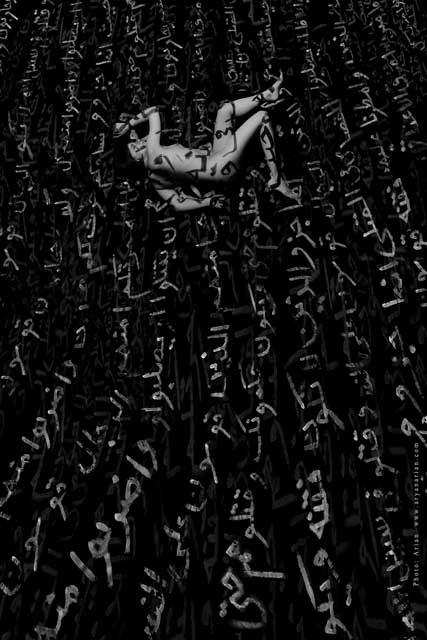

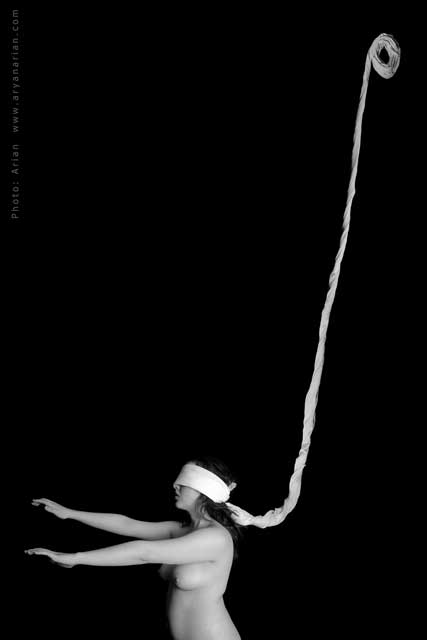

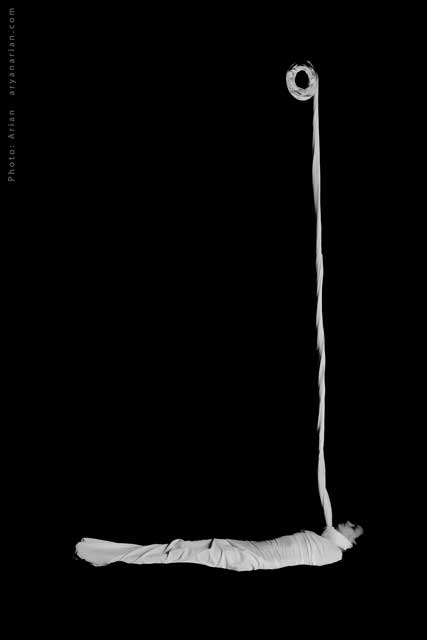

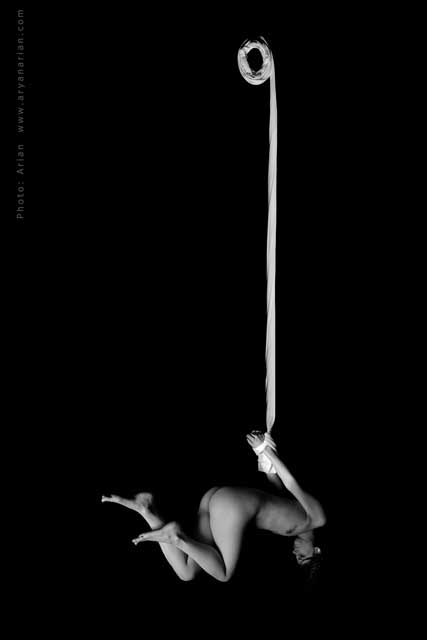

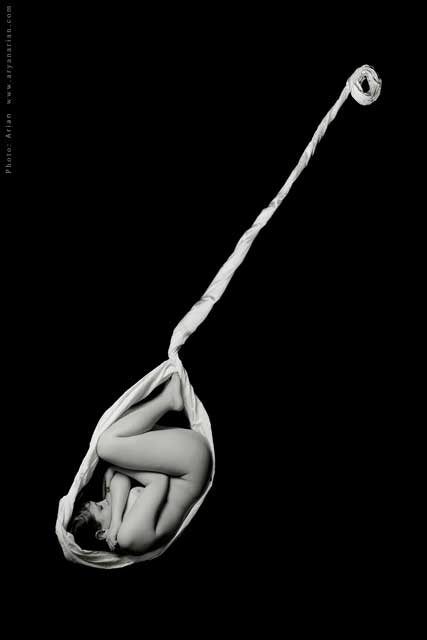

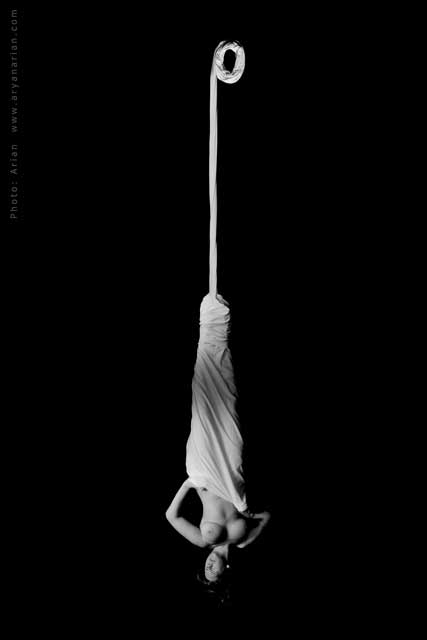

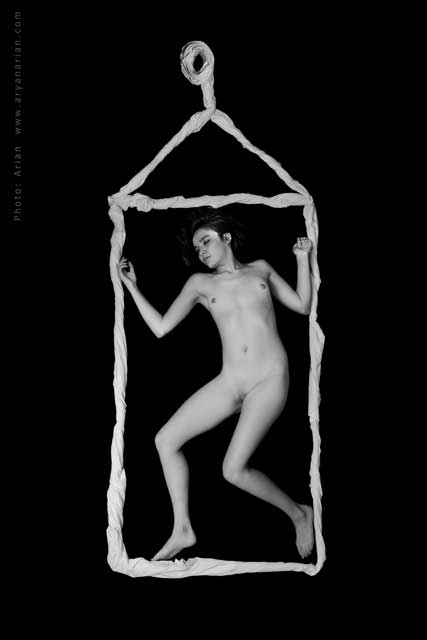

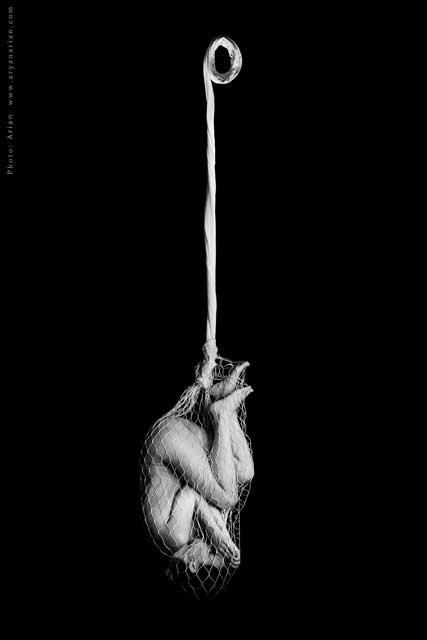

In the series Lonely in the Darkness, for example, he placed lonely nude figures against predominantly dark spaces.

In the series Lonely in the Darkness, for example, he placed lonely nude figures against predominantly dark spaces.

“Many people ask me why I take pictures of nude subjects. Often, I reply, ‘What if I’d limited myself to taking photos of landscapes? Would you have asked why I’m taking landscape photos all the time?’ Since nudity is taboo, presenting it through an art form raises questions. I, on the other hand, suggest that this issue be dropped and that we analyze photographs and their themes and contents instead.”

“From my standpoint, nude art has a few interesting aspects,” Aryan explains. “First of all, nudity makes social judgements become unimportant. With nudity, the social class and position that people’s way of dressing confers upon them fade away. Of course, the subjects of nude art still can be judged and perceived as pretty or ugly. This evaluation is nevertheless only a construct of our minds and therefore far from the truth.”

“For that reason, I select my models from ordinary women around us, who by our value system could be seen as ugly or pretty. But to me they are all equally beautiful. In other words, everyone is beautiful regardless of their appearance or shape and sizes of their bodies.”

“Both so-called modern and religious societies have the same disparaging attitude towards nude art, and view it as taboo – in a moralistic light. With a piece of nude art, it’s the naked body per se that gets the most attention. So it’s pretty hard to portray nudity as solely a formative component of an artwork. Therefore, in the majority of my works, nudity has not been used for erotic ends.”

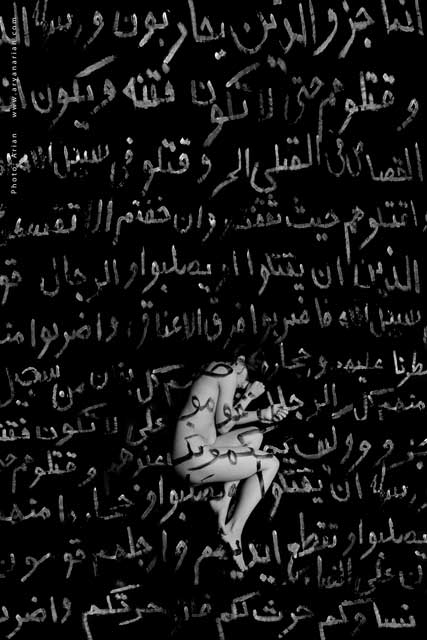

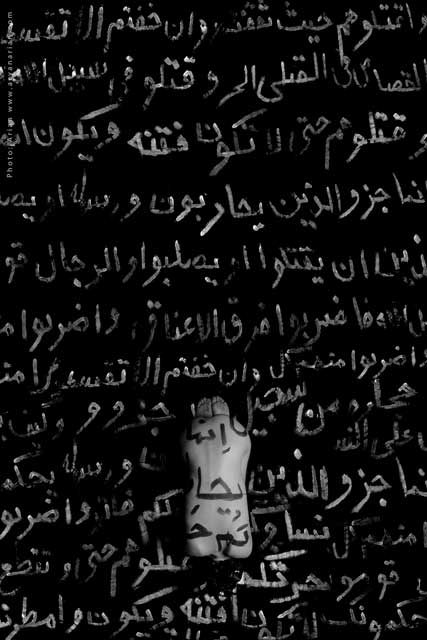

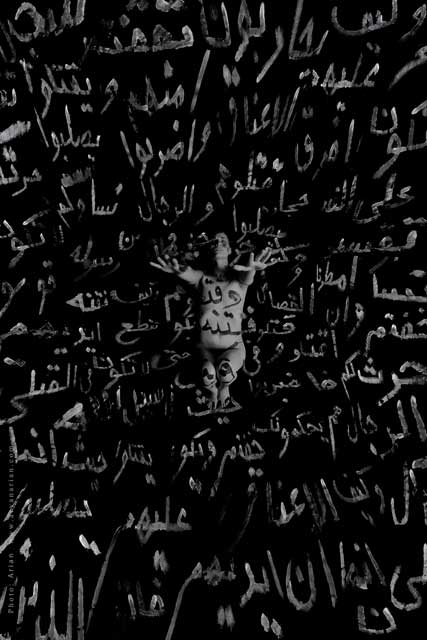

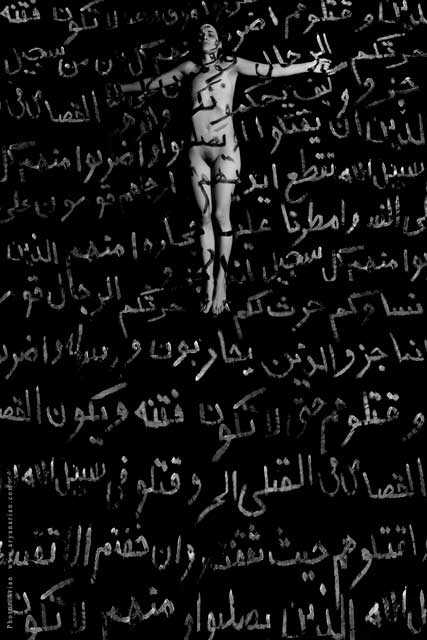

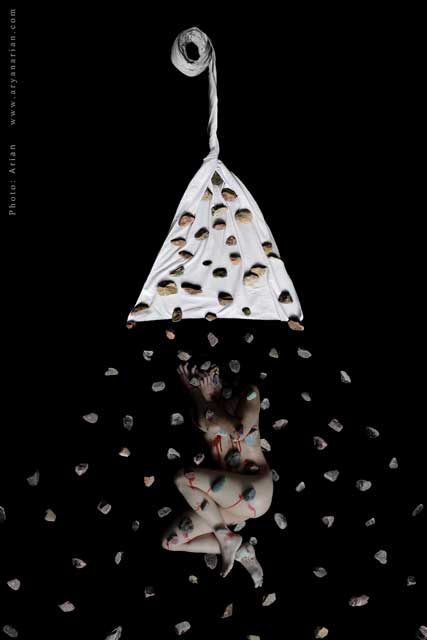

After the Lonely in the Darkness series, he highlighted “the constraints of religion and religion-induced violence” in the series Islamic Turbans and Victims of the Verses – both of which drew abundant attention.

In 2012 came Legend – “photographs influenced by Iranian painting and portraiture techniques that feature Persian carpets, the taar instrument and other recurrent visual elements of Iranian paintings, as well as my own usual themes.”

Out of that series came the photograph Mother Earth, the work that Aryan is most famous for. It has been published on hundreds of websites. Some people have even posted the photo under their own names. Yet to those who know his work, Aryan’s signature style is easily discernible.

“I was studying traditional Persian paintings for some years and had this idea in mind that one day I should take photos in which perspective is disregarded, and instead some elements of Persian paintings such as tazhib (Gilding) and Iranian symbols are present,” he explains. “I came upon the idea of using the Persian carpet as background and taking photographs from an overhead angle.”

“Unfortunately, after I uploaded one photo from this series, known as Mother Earth, Facebook deleted my account. Since I had not signed the picture, it went viral on the Internet, and in the process became subject to censorship [by Internet users], which pained me even more. Still, many Iranians use this photo on the occasion of Norouz [the Persian New Year], under different titles and without my permission. Most of these people reside in Iran.”

Why is Aryan critical of religion? “The biggest problem with religion is that by accepting its principles you are forfeited of your right to question things. Everything must be taken in faith and, just as in the military, there’s no right to question orders. If you are a faithful follower of a religion, you can commit any act of violence and then justify it as doing the correct thing according to the teachings of your religion.”

“A faith that propagates violence and murder merits no respect. Every inhumane ideology must be subject to criticism. Yet religious thugs have terrorized societies to the point that no one dares to be critical of religion. Still, fear is the biggest enemy of any artist. I’m not arguing that every artist has to be a political activist. All I’m saying is that artists must not be insensitive to the inhumane conditions around them.”

So what’s next for the filmmaker and photographer? “I am a follower of Omar Khayyam’s philosophy and live for the moment. I have no idea about the future.”