By Katayoun Shahandeh

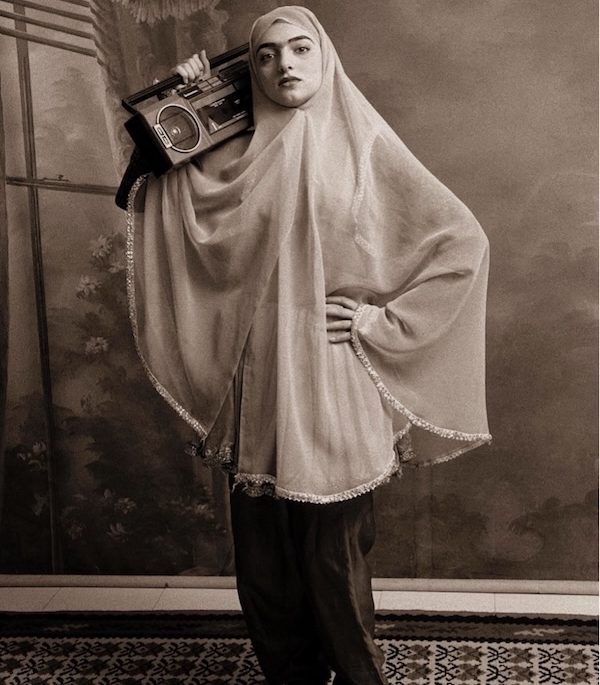

Shadi Ghadirian is one of Iran’s leading contemporary artists. One of the first artists to emerge in the post-revolutionary period, she produces photographs that juxtapose historical and contemporary elements to reflect the multifaceted reality of life and womanhood in present-day Iran. She is famous for her black-and-white images of women in 19th-century Qajar dress posing with 20th-century household appliances, such as vacuum cleaners and boomboxes.

Born in 1974 in Tehran, Ghadirian studied photography at Azad University in the Iranian capital under Bahman Jalali. After working in Iran’s first photography museum, the Akskhaneh Shahr, and helping establish the first Iranian website focusing exclusively on the discipline of photography, she embarked on a solo career. Her photographs are now in the collections of the British Museum and of the Pompidou Center in Paris, among other museums.

Ghadirian’s photographs explore themes of gender, identity, tradition, and modernity. Through staged compositions and the use of symbolism, she critiques societal norms, challenges stereotypes, and sheds light on the tensions between personal and collective identities, inspiring critical discourse.

Kayhan Life recently interviewed the artist, who lives and works in Tehran.

You were one of the first Iranian women artists to emerge in the post-Revolution period in Iran. As such, do you feel a pressure to represent Iranian women and be their voice?

I studied photography and have always been committed to this medium. One of my greatest challenges was that, after the Iran-Iraq war, photography in Iran was predominantly focused on photojournalism, with little demand or recognition for art photography. I was among the first to experiment with staged photography, a practice that was unfamiliar and unconventional at the time.

While at university, I faced significant resistance when proposing my Qajar series (1998) as my final project—it was difficult to gain acceptance for such work. Later, when I attempted to exhibit the series, finding a gallery to showcase it proved equally challenging, as the concept was still considered unusual.

My focus on women’s imagery posed its own difficulties. While I adhered to portraying them with veils, their visible faces and the broader subject of women in my work often provoked scrutiny and resistance, reflecting the ongoing complexities around this theme.

How have your personal experiences as a woman in Iran shaped your artistic vision and choices?

Living in Iran as a woman comes with many challenges, particularly the limitations on expressing everything I want through my work. Being under constant scrutiny, it’s crucial to carefully consider how we depict and speak about women. As an artist who has had the opportunity to exhibit my work internationally, I have faced heightened attention on how I represent Iran and what narratives I bring to the global stage.

Yet I believe that there is a wealth of important topics to explore, both within and outside Iran, and art—whether through photography, cinema, painting, or other forms—serves as a powerful medium to highlight these issues. Art’s ability to provoke awareness and inspire questions is one of its greatest strengths, and I see success in my work whenever I manage to engage my audience in critical reflection. Creating stories that challenge and inspire thought has always been my goal, and achieving that is deeply fulfilling.

You have always called yourself a storyteller, and there is a lot of narrative in your work. Have you ever thought of making films?

I have often reflected on the parallels between my work and cinematic production. My staged photography involves extensive planning, collaboration with a team, and careful attention to detail – lighting specialists, models, and meticulously constructed scenes – all of which makes it akin to filmmaking. In many cases, I find it challenging to fully convey my ideas in a single image, often needing a sequence to express my vision completely.

While I have considered transitioning to film, I have hesitated for several reasons. Filmmaking is a demanding medium, and I lack formal training in it. I also worry that pursuing it might distance me from photography, which I deeply love.

That said, I have explored video art and even combined it with installation work, which I see as an extension of photography, with added movement. But video pieces pose their own challenges; they require specialized exhibition spaces and are less commercially viable, making them less appealing to many galleries.

I do have ideas for stories that could be transformed into films, and I hope that one day I will have the opportunity to bring them to life. Until then, I remain committed to photography.

Your work tends to incite very strong reactions amongst audiences, especially works such as the Like Everyday series (2000). How has the public and critical reception of your work influenced your artistic journey?

It’s true that my work has faced significant criticism, especially the Like Everyday series, which sparked controversy and drew varied reactions. In Iran, the response differed greatly from the response abroad, and even within Iran, men and women reacted differently. Women connected with the images, recognizing them as reflections of their lived experiences. Feminist organizations embraced the series, using it to represent their causes, while men largely disliked it, deeming it disrespectful to women. I found it intriguing that women saw the series as truthful, while men, perhaps unsettled by its confrontation of the male gaze, criticized it.

The series brought a mix of challenges and rewards, sparking controversy while also earning widespread acclaim and igniting vital conversations about gender roles and societal expectations.

Do you have a favourite work or series?

I am fond of most of my series because I believe I addressed the right topics at the right time. However, one of my favorites is the series I created on war, a subject that remains perpetually relevant. Though I’ve explored it in two series (Nil Nil, 2008 and White Square, 2009), I feel that I will return to it again someday. Unfortunately, war and conflict are persistent parts of our lives, especially for those of us who experienced it deeply. Growing up during the eight-year Iran-Iraq war left an indelible mark on my teenage years, shaping who I am and compelling me to speak about it.

For those directly impacted, war’s memories never fade. My approach offered a feminine perspective, which is rarely seen in war photography. Instead of focusing on men on the frontline, I explored the lives of women left behind—wives, mothers, sisters, and lovers—who endure the waiting, the uncertainty, and the war’s consequences. Even in seemingly normal times, traces of war linger. I wanted to highlight the stories and struggles of women in wartime, giving voice to their often-overlooked experiences.

Can you share some of the key influences and inspirations behind your work?

The subjects I choose are ones that I have personally experienced and that have had a significant emotional impact on me—by prompting joy, sadness, or reflection. When I see that these topics also resonate with my generation, I feel compelled to explore them. Ultimately, my inspiration comes from my own life and the people closest to me.

How has your perspective on your work and its themes evolved over the years?

My perspective has evolved significantly. After nearly 30 years of work, I can see how it has changed and grown. I’m not a particularly prolific artist: I have created just 11 photographic series and four video installations. There have been periods of silence, and I am comfortable with that, as I prioritize meaningful work that satisfies me.

While much of my earlier focus was on women’s rights, addressing the challenges faced by women in Iran, my artistic interest has since broadened. Although I remain an advocate for women’s rights, I now focus more on human rights, because I believe that when they are respected, the need for feminism or women’s rights diminishes, and people naturally treat each other with dignity and equality.

Looking ahead, I might also explore environmental themes in my work.

Can you share any insights on how to navigate the art world as a contemporary artist in Iran?

With globalization and the internet, the world has become smaller, making it easier for people to learn about Iran and for Iranians to connect globally. When I first started my career, such access didn’t exist, making the process both more challenging and more intriguing.

For example, in 2000, when I was a young woman artist exhibiting in the UK, it was rare for people to encounter both my work and myself. That made the experience uniquely impactful.

Today, the art world is more interconnected, and as a contemporary Iranian artist, we are judged according to international standards, which demand greater effort and awareness. Still, there remains a mystique around Iranian artists, because they offer outsiders glimpses into a culture that many cannot directly experience. This is also true of Iranian cinema, which has long conveyed the essence of life in Iran.

As someone who has chosen to live and work in Iran, I am proud to tell stories that resonate with my homeland. My work is created with Iran and Iranians in mind, and I have consistently showcased it within the country. While I have also participated in international exhibitions, I value the opportunity to share Iran’s narratives with the world, bridging cultural gaps while staying rooted in Iran’s unique identity.

What are you currently working on?

I am working on my first installation for an exhibition in which 20 artists will showcase their work in a large industrial estate near Tehran. While I may also photograph it, my main focus is the installation. I am deeply immersed in the project and excited about it.

I am also compiling material for a book featuring all of my works, which I hope to have ready by next year. Both projects are keeping me creatively engaged, and I look forward to seeing them come to fruition.