By Kayhan Life Staff

A rare collection of enamel objects from the Qajar dynasty in 19th-century Persia has been exhibited in London and is being offered for sale in its entirety for $2.2 million.

The 72 precious objects, owned by a London-based Iranian collector, are detailed and illustrated in the catalogue of an exhibition titled “The Rose and the Nightingale” organized by Forge Lynch — an Indian, Islamic and ancient art dealership based in London and New York. The objects range from enameled earrings, broaches and pendants to gold daggers, boxes and qalyan (water pipe) cups. The aim is to sell the collection to a museum or institution on behalf of the client, and the process is likely to take a year or more.

“As a dealer in Islamic and Indian art, one is always looking for a new area as the theme of an exhibition,” said Brendan Lynch, an Islamic art dealer and a co-founder of Forge Lynch, in an interview at the gallery. “Qajar enamels are a fascinating area that nobody has really done.”

Lynch described Qajar art as a thrilling category of Persian art, but one that was long neglected. He said traditional collectors in Europe and the United States and in the expatriate Iranian community had tended to concentrate on medieval pottery and metalwork from 8th- to 13th-century Persia, as well as objects from the 15th-century Timurid period, and from the 17th-century Safavid period, when the arts experienced a golden age under Shah Abbas I.

That was perhaps because, at first glance, Qajar artworks were not to everyone’s taste, Lynch acknowledged.

“They’re blue, and they’re pink, and they have a candyish palette of colors, so people slightly recoil from that,” he said, but then “they get drawn in,” because of the “intriguing and perhaps a bit unusual” colors, but also because of the sheer quality of the painting.

“Curators worldwide in museums with specialist Islamic departments are now looking at these objects,” he said. So are collectors, because “this is an area where you can buy objects that have been circulating in Europe for considerable time and have adequate provenance,” and they are “not necessarily individually expensive.”

The Qajar dynasty ruled over Iran between the late 18th century and the early 20th century. British interest in Qajar art was stirred up after two of the dynasty’s rulers — Fath Ali Shah and Nasser-ed-din Shah – traveled to England. Nasser-ed-Din Shah was hosted by Queen Victoria on three separate trips, and he was made a Knight of the Order of the Garter by the Queen, according to the exhibition catalogue.

The first public exhibition in Britain of “Persian and Arab Art” was organized in 1885 at Burlington House in London by the painter and collector Henry Wallis, a member of the Burlington Fine Art Club. Following that exhibition, the Victoria & Albert Museum and the British Museum both made major acquisitions of Persian art.

Much more recently, Lynch said, two major exhibitions of Qajar art were held in the United States and Europe. One was “Persian Royal Paintings: The Qajar Epoch 1785-1925,” curated by Layla Diba in 1998-99 and held at the Brooklyn Museum in New York, the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles and the Brunei Gallery in London. The other was the 2018 exhibition “L’Empire des Roses” at the Louvre Lens in northern France, a comprehensive exhibition of 400 works of art including Qajar enamels, with an important catalogue.

During the conversation with Kayhan Life, Lynch provided further details on the Qajar enamel collection.

Why did you decide to put on this exhibition and sale?

One of my clients is a London-based Iranian collector who has been forming a collection of Persian art over the last 30 years — mostly at auction, sometimes privately. Some of the objects came from the collection of a well-known Iranian businessman, Mahmoud Khayami. Others came from the collection of the Ariyeh family living in New York. So our client was buying from very good sources, and focusing on Qajar enamels.

Qajar enamels are very finely painted, by well-known Qajar painters, who were quite diverse in their skills – producing pen boxes, enamel pieces of jewelry, and a range of other objects.

I asked our client if he wished to put part of his collection on the market, because a museum in America was becoming very interested in Qajar art. The answer was always no. I then realized that our client had 72 enamel pieces. It’s a lot. So eventually we had the idea of endeavoring to sell it as a collection.

Some of the objects are repeatable, but many of the better things are not. You would have to spend another 30 years or perhaps longer to gather a collection like this again.

Which institutions are you offering the collection to?

We will be approaching museums of Islamic art throughout the world, probably concentrating on the Gulf and parts of Asia. We have had some inquiries.

When you have a collection of almost anything that you want to sell to an institution, the first thing you have to ensure is that they don’t have any art of that type. It’s no good if they’ve got a hundred examples of Qajar enamel. They are not going to want a whole collection.

We are used to selling individual objects to museums around the world. Even the sale of one object may take a year or a year and a half — from the time you discuss it with the curator until they go through the various stages of approval, condition verification, funding, shipping and acquisition. It’s even more difficult when you’re selling a collection.

Can you describe a few highlights from the collection?

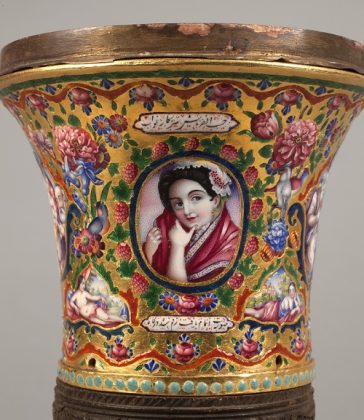

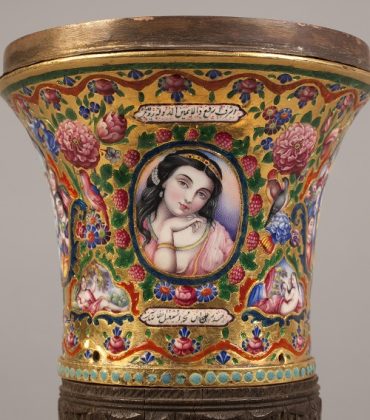

One of the most exceptional pieces is a qalyan (water pipe) cup, the most typical thing that people think of when you say ‘Qajar enamels’: wonderful cups which were made in quantity at the court. There was a great fashion for them. They are adorned with not only casual portraits of everything from courtesans to rulers, but also quite a lot of European religious iconography and imagery, which would probably have crept into the courts through the missionaries circulating prints. There’s the enduring subject of the mother and child, which occurs quite a lot, and is universal.

What is amazing is the sophistication of the techniques, the way in which these wonderful flowers, the roses and the irises, are painted – with the greatest skill, and comparable in quality to the finest enamels in European art.

This particular cup was commissioned for Prince Masoud Mirza Zill al-Sultan, fourth son of Nasser ed Din Shah. It’s a really wonderful and precious example, and signed by the painter. He was called Heydar Ali, and was the son of the artist Mohammed Esmail, who flourished under Nasser ed Din Shah.

What are some other highlights?

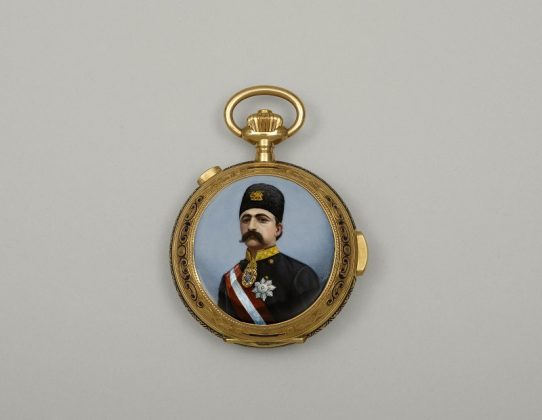

There’s a very charming, probably mid-19th-century portrait of a young man, possibly Nasser-ed-Din Shah. It’s a slightly informal portrait, in the sense that he’s in a blue tunic with gold buttons, and has a conical Astrakhan hat. This is decorated with great sophistication. The borders are not the pink and blue Qajar colors, but rather orange and green, which creates a much more subtle effect.

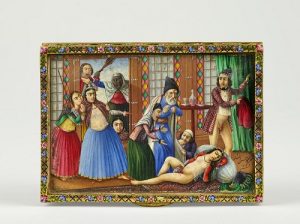

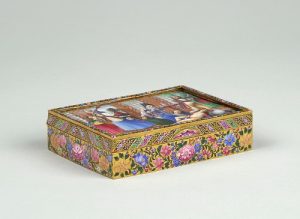

What about the erotic box?

This rather controversial erotic box is very interesting for a number of reasons, mainly because it’s actually signed and dated, but also because of the subject matter. It’s a watercolor underneath a sheet of glass, which I think has been in the box since it was painted.

It’s the traditional theme of the surprised lovers. What you’ve got here is a slightly graphic scene of a nude young girl with a half naked young man who have been caught together in a chamber — by what we’ve been told may be the girl’s father, and a group of court ladies. The artist, Mohammed Hassan Afshar, would have wanted to create something unusual so that he could record the shock and surprise on the faces of these people. They’re almost cartoonish in some ways: They’re caricatures.

Signed Muhammad Hasan Afshar

Possibly Shiraz, Persia, dated A.H. 1262 / 1845-6 A.D.

Signed Muhammad Hasan Afshar

Possibly Shiraz, Persia, dated A.H. 1262 / 1845-6 A.D.

The idea was to paint something different and interesting that would be much discussed, and he certainly achieved that. It was obviously an object that would not have been shown in public, but would have been shared by men of the court, or one of the rulers as a piece to produce amongst his friends.

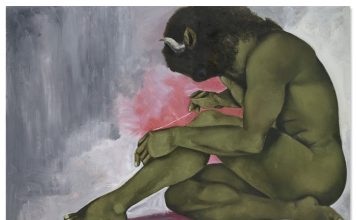

Many Iranian collectors nowadays have a passion for the contemporary.

Indeed. I think that’s very much a product of the new century.

There was a seismic change worldwide at the beginning of the 21st century, when the focus of everyone under 40 became contemporary art — whether they were from India, Iran or Greece. It’s a very nationalistic thing, and it seems to be an area that young people are very keen to focus on. They want a few good and even great pieces, and want to live in a less cluttered environment. Taste has changed – that’s universal.