By

SOURCE: THE CONVERSATION

The High Court unanimously ruled today that the Australian government can keep asylum seekers in immigration detention indefinitely in cases where they do not “voluntarily” cooperate with their own deportation.

This includes, for example, when a person refuses to apply for travel documents due to a longstanding fear for their life if returned to their home country.

At the crux of today’s ruling is the legal fiction that indefinite immigration detention can remain “non-punitive” and legitimate if a person is detained for the “purpose” of their eventual removal from Australia – even if the human effects of this detention are harmful and experienced as punishment.

The decision places a significant limit on the precedent set by last year’s landmark High Court ruling that indefinite immigration detention is unlawful if there is “no real prospect” of a person’s deportation in the foreseeable future.

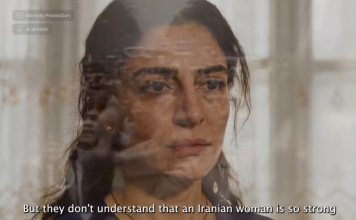

The case centred around “ASF17”, a bisexual Iranian man who has been held in closed immigration detention in Australia for more than ten years. Although Iran criminalises homosexual activity, ASF17 was found not to be a refugee under Australia’s fast-track asylum claim process, which many experts have deemed to be flawed and discriminatory.

Under Australian law, the government is required to deport ASF17 as soon as reasonably practicable back to Iran – or release him from detention if there is “no real prospect” of deportation.

The government argued before the court, however, that it was not required to release him because he was not cooperating in his own deportation. He had refused to seek the required travel documents from the Iranian government.

The Australian government argued that ASF17 could bring his indefinite detention to an end at any time by voluntarily returning to Iran, or by taking the necessary steps to allow the government to deport him.

ASF17’s lawyers argued he had “good reason” for not cooperating with his own deportation – he feared for his life if he returned to Iran. As he stated during cross-examination during the case:

if I didn’t fear harm, I wouldn’t have stayed in this camp for 10 years. I would have quickly gone back to begin with the first day. Who […] will leave their family and prefer the prison?

ASF17 was prepared to be deported to any country other than Iran. And Iran would not have even allowed him to return, as it does not accept forced or involuntary deportations of its citizens from other countries.

The Australian government acknowledged there was no reasonable prospect of him being sent anywhere else.

The court found there was still a “real prospect” of ASF17’s removal, given it depended in part on his conduct. Central to the court’s verdict was how it characterised ASF17’s position:

He has decided not to cooperate. He has the capacity to change his mind. He chooses not to do so.

The court held that in such circumstances, detention remained “non-punitive” and therefore lawful. By making this finding, the court was basically saying that the constitutional limit on the government’s power to keep a person in indefinite detention does not apply in such cases.

The court emphasised the language of choice and capacity, saying it has to be within “the power” of the detainee to decide not to assist in their own deportation. The court left open an exception for those who are medically incapacitated.

Although it was an unanimous verdict, Justice James Edelson did provide a separate reasoning that stressed the possible “gaps” in the Migration Act for recognising refugees. This included where the asylum process might have overlooked key issues. Or, in cases where a decision to refuse refugee status is “flawed” but upheld for other reasons, such as the person travelled to Australia on a forged document.

While Edelson stressed the High Court could not revisit the “factual basis” of ASF17’s asylum case, he noted the immigration minister could still exercise discretion to allow his claim to be reassessed or grant him a visa.

Edelson said this was an alternative to keeping ASF17 in detention until he provided consent

to be returned to a country where he might be executed if he were to express, privately and consensually, what has been found to be his genuine sexual identity.

Today’s decision reflects the government’s relentless campaign to limit the effects of last year’s High Court ruling that indefinite immigration detention was unlawful. This decision led to the immediate release of over a hundred people.

The controversial draft legislation now before parliament is widely seen as a direct response to ASF17’s case. If passed, the legislation will compel a person in immigration detention to cooperate in their own deportation. The bill goes much further than the High Court’s decision, however, by making refusal to cooperate in deportation a criminal offence.

The ASF17 case also highlights the moral contradictions between Australia’s international and domestic politics.

Australia has imposed sanctions against members of the Iranian regime responsible for egregious human rights abuses and violations. In 2022, a Senate Committee report recommended the Australian government increase the number of visas offered to Iranians with a:

particular focus on women, girls and persecuted minorities seeking to escape the regime. Iranians in Australia on temporary visas who cannot safely return to Iran due to the current crisis and policies of the [Iranian regime] should not be required to do so.

Yet, rather than doing just that in ASF17’s case, the government continues to treat Iranian asylum seekers with suspicion. In fact, the bill before parliament would even make it possible for the immigration minister to apply a blanket ban on all people from countries that refuse to accept the return of deported citizens, such as Iran.

As a result of today’s decision, up to 200 people may remain indefinitely detained. The decision also impacts thousands of others who have been denied asylum by the flawed “fast-track process” and have been living in the Australian community for over a decade, but fear returning to their home nations due to persecution.

Ultimately, the decision is a missed opportunity to move away from Australia’s harmful use of immigration detention that allows for some people to be detained their entire lives.