By Tim Cornwell

When the wife of the British governor of Mauritius learned that Reza Shah, the former Shah of Iran, was to make the island his home in exile, she went out of her way to welcome him. Lady Alice Clifford and her friends stitched an Iranian flag with the lion-and-sun emblem to fly over the three-storey villa where Reza Shah and his family were to live.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Vol-Ory-rezashah.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Chateau Val Ory Moka in the Republic of Mauritius, where Reza Shah (1878-1944), the founder of the Pahlavi dynasty, spent the first six months of his life in exile. KAYHAN LONDON./ ” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

In a local museum, Lady Clifford found a magnificent four-poster bed that had belonged to one of Napoleon’s generals, and had it decorated with a royal crown for the former sovereign to rest on. But Reza Shah slept as ever on a rug on the floor. The frogs of Mauritius kept him awake at night, and he sent his servants to try and round them up.

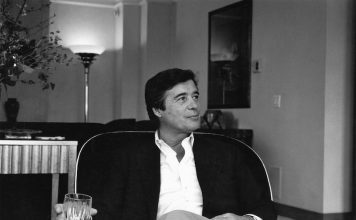

These are a few of the interesting anecdotes contained in “The Fall of Reza Shah: The Abdication, Exile, and Death of Modern Iran’s Founder,” by Shaul Bakhash, a historian of Iran. It’s the first complete chronicle of the strange and sad three-year exile of the founder of the Pahlavi dynasty, who reshaped the country during his more than 20-year reign, and died in South Africa after his forced abdication.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/the-fall-of-reza-shah.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”The Fall of Reza Shah.” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Bakhash draws on British and Iranian sources to retell the story of Reza Shah’s precipitous fall from power in 1941, and the journeys that followed, including to an island that he came to dislike intensely.

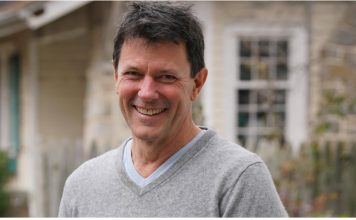

“There is this story of a once very powerful man, suddenly broken by invasion, the collapse of his army, the need to abdicate, and exile,” said Bakhash, an Iranian-American professor at George Mason University in Virginia, in an interview. “It is about a great man, a powerful man’s fall from power.”

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/رضاشاه.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Reza Shah.” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/rezashah.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Reza Shah.” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/zimg_002_4.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Reza Shah.” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

For both the British and the Iranians, he said, his journey to remote Mauritius inevitably reminded them of “the idea of Napoleon on [the island of] St. Helena. This is the story of Iran’s Napoleon on his St. Helena.”

Professor Bakhash said his admiration for Reza Shah grew as he researched the book: “I always thought he had done a great deal, but as I worked on the book. I became even more impressed by what he achieved, given the state of the country when he seized power.”

It’s a century since an ill-educated villager’s son named Reza Khan marched his Cossack soldiers onto Tehran at the start of a trajectory that would make him the country’s military strongman, prime minister, and finally, king in 1926.

Reza Shah is credited with modernizing the country with new institutions and new industries that leave a legacy to this day. He took a badly weakened Iran in 1921 and turned it into a modern state.

Given that he came from a village and had “very limited education,” his “sheer ability” and meteoric rise through the ranks of Cossack brigade was unexpected, said Bakhash. “It is astonishing that a man of this kind of background absorbed and went along with the ideas of the most prominent reformist thinkers of the time.”

Yet when World War II broke out in 1939, Reza Shah declared Iran’s neutrality: the country had vital trade relations with both sides in the conflict. Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 made Iran a vital overland route from the Persian Gulf to supply Russia. That led to the Anglo-Soviet invasion in August. The stated reason was that hundreds of Germans working in Iran could become a fifth column or even stage a coup.

Anticipating that Reza Shah might resist or obstruct, Britain wanted him out of the way. The Foreign Office authorized three days of broadcasts on the BBC’s Persian-language service of “direct and escalating criticism of Reza Shah” for confiscating land, using forced labor on his properties, manipulating elections, and making unlawful arrests and executions, among other allegations. The material for the broadcasts had been prepared by the then press attaché in Tehran, Ann Lambton, who later became a leading scholar of Iran.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/17Day1314_rezashah.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”KAYHAN LONDON./ ” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

In 1941, Reza Shah was forced to abdicate by the British.

Bakhash said he “came away more impressed with Reza Shah’s achievements” than he was before, “though always thinking he could have done more to create democratic institutions in Iran.” And he “couldn’t help but feel sympathy for him in this period of exile, when he was a bit of a broken man.”

At the same time, according to Bakhash, Reza Shah amassed a huge personal fortune that included all or part of some 2,000 villages. Political opponents or prominent allies who fell into disfavour ended up in prison if not dead.

The book tells the story of how a feared and powerful ruler, who had only ever worn military uniform, donned an ill-fitting suit for the first time as he waited to sail away into exile from the port of Bandar Abbas. “Bring it down,” Reza Shah said, seeing his picture on the wall in the office of the director of customs. “There is no need of my picture anymore.” He waved away the honor guard, too: “What is all this for? It’s not at all necessary.”

Mauritius was far from the first choice — certainly for the women in the Shah’s family, who thought of Argentina, for its climate and distance from the main theater of conflict in World War II. British officials, however, wanted to keep the ex-Shah under a British eye. Lord Linlinthgow, the Viceroy of India, barred any stay in India because he believed the dethroned Shah’s presence could stir up local Muslims.

British officials’ possible choices for replacement rulers included Prince Mohammad Hassan Qajar, the younger brother of the last ruler of the Qajar dynasty, Ahmad Shah. “Prince Hassan strikes me as tractable and intelligent but not as a strong personality, while his son Hamid is an excellent type, but speaks no Persian,” Sir Anthony Eden, the British foreign secretary, cabled to Tehran. Despite fears that he had pro-German sympathies, British and Soviet officials agreed that Crown Prince Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was a suitable successor.

According to Bakhash’s book, Reza Shah’s retinue on his travels included his third wife, Esmat, her step-sister and a lady-in-waiting, six sons and two daughters, his private secretary, his son-in-law, who served as his aide, a cook, and five additional servants. His vast wealth amassed over 20 years — including the equivalent of 10 million pounds in cash in bank accounts alone — were handed over to his son, and from then on Reza Shah relied on transfers from Tehran, Bakhash writes.

The luggage for his journey into exile included a Cadillac and a Mercedes Benz, while his daughter Princess Shams persuaded the British to provide a two-seater Sunbeam Talbot sports car for her outings.

On Mauritius, he rose early, and breakfasted alone, taking long regular walks and avoiding outings because “I am a prisoner, and I must behave like a prisoner.” When Governor Clifford, at tea, asked him how he felt, he said: “We are prisoners … Mauritius is a prison, albeit a big one. We are accustomed to great open spaces and mountains to which to escape the heat. To us this existence is unreal—a sort of death in life.”

In one poignant moment, when he was due to join a dinner to mark the signing of a tripartite agreement between Iran, Britain, and the Soviet Union, his son-in-law found him sitting in bed with a bowtie in his hands. “God grant me death. What is this harness I must wear around my neck?”

Negotiations for the agreement in 1942 saw the family win permission to travel to Canada. But on arrival in Durban, South Africa, Reza Shah took a liking to the country and instead settled in Johannesburg.

In March 1944, he wrote to Princess Shams: “My physical condition is not bad; but as to my state of mind, it is better not to speak.” That June, he suffered a fatal heart attack, and died the following month at the age of 66.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/rezashah_1.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Reza Shah.” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]