REUTERS: The success with which earlier protest movements in Tunisia and Egypt had toppled dictators Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali and Hosni Mubarak, as well as NATO’s air campaign against Muammar Gaddafi’s forces in Libya, seemed outwardly to present an opportunity for change in Bashar al-Assad’s Syria.

Instead, the Syrian uprising turned into an insurgency and then a bloody civil war.

By December of 2011, 133 countries in the United Nations General Assembly (including Aotearoa New Zealand) were strongly condemning the Syrian authorities’ “grave and systematic human rights violations” in its response to the uprising.

Alas, this was to no avail. In the past decade, 7 million Syrians (from a pre-conflict population of 22 million) have been internally displaced, and 5.6 million have fled to neighbouring countries.

More than 500,000 have been killed, including 55,000 children. According to the UN Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, thousands of civilians have been subject to torture, sexual violence or death in detention, or have disappeared.

The dire circumstances of more than 64,000 mostly women and children being held in the Al-Hol and Al-Roj detention camps in north-eastern Syria have become the most recent statistic in the Syrian tragedy.

How did this ongoing disaster happen? While the Syrian conflict is complex, it is possible to identify three things that facilitated the militarisation of the uprising and al-Assad’s political survival.

Like their counterparts in neighbouring countries, Syrians faced a pervasive mukhabarat (security establishment), poverty and the absence of basic freedoms.

Their desire for change found early expression when a group of schoolboys painted a slogan, first seen in Tunisia and then in Tahrir square in Cairo, onto a wall in the southern Syrian city of Daraa: الشعب يريد إسقاط النظام (as-shab yurid isqat an-nizam), translated as “the people want the fall of the regime”.

But the al-Assad government did not fall. It violently cracked down on the protest movement. In Daraa, the schoolboys were detained and tortured. When the mukhabarat dismissed the tribal elders who intervened on their behalf, it sparked demonstrations in the city.

The demonstrators were met with live ammunition and later tanks. Whole neighbourhoods and villages were put under siege. This excessive use of violence against demonstrators in Daraa and elsewhere militarised the Syrian uprising and undermined the protest movement.

The UN Security Council, initially slow to react, became no more than a witness to the violence in Syria.

Seven months after the protests in Daraa began, a resolution tabled by France, the UK, Germany and Portugal condemned Syria’s human rights violations, and raised the potential use of force under Article 41 (Chapter VII) of the UN Charter.

Russia and China vetoed the resolution, and non-permanent members India, Brazil, South Africa and Lebanon abstained. No punitive action occurred.

Opposition to the draft resolution was motivated by what had happened in Libya. On March 17 2011, UN Security Council Resolution 1973 had authorised “necessary measures” under Chapter VII of the UN Charter to protect Libyan civilians against Gaddafi’s military.

The UN-sanctioned, NATO-led military campaign began two days later, but did not cease after the feared attack against civilians in Benghazi was foiled. It continued for seven months until Gaddafi was captured and killed.

Russia’s veto of the first Syrian UN Security Council resolution was based on a suspicion that regime change, as had occurred in Libya, was also planned for Syria.

But Russia has gone on to veto a further 15 resolutions, rendering the security council largely impotent in the face of a war that has seen thousands of Syrian civilians killed, maimed, detained, tortured and forcibly displaced.

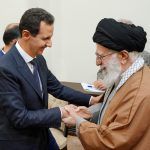

In late 2016, Syrian forces, backed by Russia and Iran, recaptured eastern Aleppo. The battle for the city had been a prolonged, bloody and strategically important standoff between government forces and anti-government armed groups that had taken a terrible toll on civilians.

For ten years, al-Assad’s permanent representative to the security council had used the threat of terrorism to justify sieges on whole cities and neighbourhoods, the use of barrel bombs on civilians, and attacks on medical personnel and facilities.

However, in the first six months of the Syrian uprising, al-Assad decreed an amnesty for “political prisoners”. At least four radical Islamists who later joined or formed militias were among those pardoned.

When Aleppo fell, Aotearoa New Zealand was serving as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council. Then-Prime Minister John Key told the security council that although terrorism was a major consequence of the Syrian war, “it did not cause it”.

Later, as Aotearoa New Zealand’s term came to an end in December 2016, its permanent representative stated:

I choose to believe the Secretary-General and the people working for him when they say the issue is not terrorism, but it is barbarism.

Without denying the legacy of UN-designated terrorist groups Islamic State (ISIS) and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (former Jabhat al-Nusra) in the Syria conflict, Aotearoa New Zealand was right to reject the Syrian state’s justification for its actions.

One minor irony in all this is that the same Syrian permanent representative to the UN was also, in his capacity as rapporteur for the UN Decolonisation Committee, charged with monitoring Aotearoa New Zealand’s administration of Tokelau.

However, this authoritarian absurdity pales in comparison to an ongoing tragedy in Syria. What Key said to the UN in 2016 remains true: a political solution is the only way out of this conflict.