By Adom Sabanchian

The Armenian community in Iran has a long and rich history.

There are the indigenous Armenians who inhabited the territory that is Iran for millennia. And there are those who migrated to Iran and settled there in different periods. A first wave arrived in the early 17th century, under Shah Abbas. There were more recent waves in the 20th century. As a result, there are cultural, educational and class differences between the Armenians of Iran. Despite this, the community enjoys a degree of homogeneity.

Civil-society organizations emerged among Armenians — including Armenian women — much earlier than in the mainstream Muslim population: from the mid-19th century onwards. This was especially true among Armenians living in the northern region of Azerbaijan and its capital Tabriz. Because of the geographical proximity to the Russian Empire, the Armenians of Iran became influenced by the Armenians living on the other side.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/2008-11-16T120000Z_1651131564_GM1E4BG1JOF01_RTRMADP_3_IRAN-scaled.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”REUTERS/Raheb Homavandi (IRAN)” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” caption=”Iran’s St Stepanos Church, a medieval Armenian Christian place of worship, is seen near the city of Jolfa, about 500 km (310 miles) northwest of Tehran. In July 2008, the three Armenian monastic ensembles of Iran: St Thaddeus (Black Church), St Stepanos and the chapel of Dzordzor were added to the UNESCO list of World Heritage sites.” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Tabriz also benefited from the arrival of Armenians from the Ottoman Empire and from Russia, later the Soviet Union. They introduced elements of modernity to Iranian society at the time.

Two prominent Iranian-Armenian scholars based in California, Dr. Houri Berberian and Dr. Talinn Grigor, are researching the history of the activities of the Armenian Women’s Collective in Iran. They are aiming to publish it in a book titled Contesting the Silences: Armenian Women and Iran’s Modernity.

Houri Berberian is Professor of History, Meghrouni Family Presidential Chair in Armenian Studies, and Director of the Center for Armenian Studies at the University of California, Irvine. Her research interests include revolutionary movements, women and gender, and identity and diaspora.

Talinn Grigor is a Professor of Art History and Chair of the Art History Program at the University of California, Davis. Her research focuses on 19th– to 21st-century art and architectural histories through the framework of postcolonial and critical theories, grounded in Iran and Parsi India.

Kayhan Life recently spoke to them.

Based on the research that you have conducted so far, what is unique about the history of Armenian women in Iran?

When we started to think about this project, it became painfully obvious early on that there was a dearth of studies on Armenian women, and that although there had been a growing scholarship on Armenian women in the Ottoman Empire, Armenian women in Iran had fallen by the wayside. The question was, how would one write such a history?

We decided to focus on the representation of women by others and by themselves, and to do so through an exploration of the collective, organizational or institutional history of women that also challenged the [male-dominated] and national/ist narrative or commonly accepted discourse about women.

It is noteworthy that in the Middle East, Iran has been unique in its generally good treatment of its Armenian minority. To the credit of the Iranian state and the general Muslim population, this has opened up many opportunities in Iran for Armenians that were otherwise unavailable in other parts of the Middle East, especially in the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish Republic. There are numerous such examples — from the special privileges granted to New Julfa’s Armenians during the Safavid period to the collaboration and role of Armenians in the Constitutional Revolution. One could say that Iran has historically valued its population’s diversity and has more often than not integrated its margins into the center.

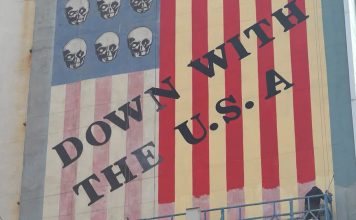

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/2009-04-24T120000Z_271342336_GM1E54O1TYU01_RTRMADP_3_IRAN-scaled.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”REUTERS./” align=”center” lightbox=”off” captionsrc=”custom” caption=”FILE PHOTO: Iranian Armenians shout anti-Turkey slogans during a gathering at a church in central Tehran. They gathered at the Holy Sarkiss church in Tehran to mark the killing of Armenians by Ottoman Turks in 1915. ” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Can you speak about the Armenian women who organized and ran activities — mainly educational ones — within mainstream women’s organizations in Iran?

Many Armenian-Iranian women rose in mainstream Iranian society as educators, architects, lawyers, artists, and scientists by choosing not to go to Armenian schools, or to be members of Armenian organizations and clubs, or marry within the community. Much of their success was based on their effective integration in broader Iranian society and its educational, professional, and state institutions. Some deliberately stayed away from Armenian women’s groups that prioritized being Armenian and being women as an ideological stance, [because of] their perception of these community organizations as narrow minded, conservative, or insular. Yet, it is within this very community that many women found a way to contribute through organizations and civic activities in the face of a rather rigid patriarchy.

This book focuses on those organisations that self-identified as both Armenian and women so that we could then explain how they in turn positioned themselves.

Do you agree that the way the Armenian Community, including women’s organizations, have affected Iranian society is very indirect? While it is a fact that Armenians have considerably contributed to the development in Iran, haven’t they managed to do this without being sufficiently integrated in Iran and even by maintaining their rather strict isolated community and cultural life?

The degree of contribution and isolation of any minority group is contingent on the policies of the larger host society. Therefore, this question can only be answered [by taking into consideration] the period since the Achaemenids, when Armenians are mentioned for the first time in historical records on the walls of Persepolis.

Since then, as both neighbor and minority, their position has shifted: from sharing royal power during the Parthian/Arsacid reign, to losing basic privileges such as riding on horseback under the Qajars.

In our book, we are looking at these strategies of inclusion and exclusion—and the societal perceptions attached to them — from the angle of Armenian women’s agency, not just in and out of Iranian society but also their inclusion/exclusion from structures of power within their own Armenian community.

This is very interesting and important work. Many of us non-Armenian Iranians grew up knowing many amazing Armenian-Iranian women and heard about them from our parents and loved, admired and respected them. My mother’s best friend in her 20s (she passed away last year at the age of 83) was her Armenian colleague for example and she remembered her lovingly till the end of her life. Or one of my father’s cousins – Mostafa Bozorgnia who was killed by the Iranian regime in what has come to be known as Rooz Daneshjoo had an Armenian fiance and so many other such examples in my own life with Armenian classmates at Shiraz U, in my work with the UN in Iran, friends etc. I would love to read such a book.