By Nazanine Nouri

What’s next for Iran?

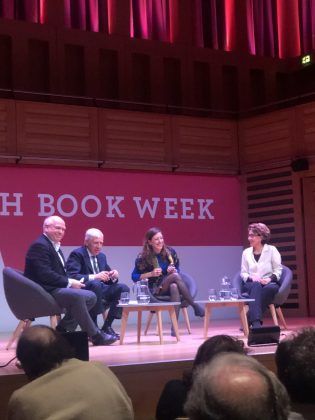

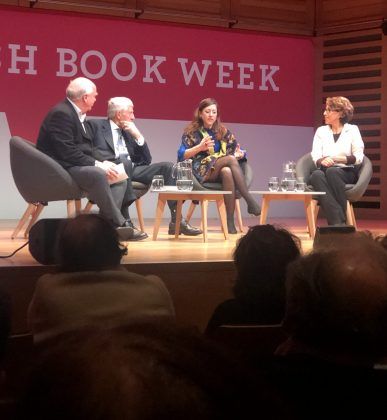

That was the title of a panel discussion in London with the U.K.’s former Foreign Secretary Jack Straw and two Iranian-born speakers: Sanam Vakil, deputy director of the Middle East and North Africa program at Chatham House, the London-based think tank; and Nazenin Ansari, managing editor of Kayhan London and Kayhan Life.

The sold-out debate was held in a 400-seat auditorium at King’s Place, a newly built London venue, as part of a series of events during Jewish Book Week. Straw recently published a book on Iran, based on his travels there, titled “The English Job: Understanding Iran.”

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/nazansauiowioqwq-e1583247224921.jpeg” panorama=”off” credit=”KAYHAN LIFE” align=”center” lightbox=”off” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Ansari kicked off the discussion with an update on the worrying impact of the coronavirus on Iran. She said the disease was spreading because of the Iranian government’s unpreparedness, the corrupt trade in masks and other medical equipment, and the fact that the real data was not being published. She quoted a member of the medical engineering faculty at Shahid Beheshti University in Tehran as saying that the fatalities from the virus could rise to levels reached in the Iran-Iraq War, or 500,000 people.

Iran has the highest number of coronavirus deaths outside China. As of yesterday, it had officially reported 66 deaths, while the total number of infected people had risen to 1,501. Among those who perished was a member of the Expediency Council. Several other government officials have been infected by the virus.

Vakil agreed that the Islamic Republic “really miscalculated and didn’t see the impact of corona.” The government was too busy focusing on domestic unrest and the population’s reaction to U.S. economic sanctions, she said: The very proof of their unpreparedness was that members of Iran’s own leadership had been infected by the virus. “They’re now going to be all hands on deck,” she predicted.

The contagion comes at a very challenging time for the Islamic Republic. In November, Iranian authorities killed hundreds of demonstrators protesting a fuel price hike, firing live bullets and shutting down the Internet to prevent coverage. Two months later, its highest-ranking military commander, Qasem Soleimani, was killed by a U.S. drone strike in Iraq. A few days later, Iranian missiles mistakenly shot down a Ukrainian airliner, killing all 176 people on board.

The panel’s three speakers all agreed that the situation in Iran was dire. They disagreed on what could, or should, happen next.

Straw was highly critical of U.S. President Donald Trump, his pullout of the 2015 Iran nuclear deal, and the harsh sanctions he had imposed against Iran. He described the Trump view of Iran as “vulgar and one-dimensional,” and said the U.S. administration perceived Iran as “a monolith of mullahs” which, if placed under enough pressure, “would crack. That’s not the case.” U.S. actions were likely to lead to more severe repression, he warned, and eventually, to a dictatorship by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

Straw pointed out that it was “simply not the case” that Iran was a “monolithic theocracy” and that every action it took was “all scripted.” There was an elite, but unlike in the Soviet Union, it consisted of “seriously warring factions.” For example, Zarif had “no more control” over the detention of Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe (the British-Iranian woman who has been detained since April 2016) “than anybody here,” he said, looking at the audience.

He said the West should go back to its policy of negotiating with, and thereby strengthening, the reformist camp in Iran, represented by President Hassan Rouhani and Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif. After the nuclear deal was signed by Iran and Western powers in 2015, he said, the Iranian economy grew 10 percent. But since the Trump sanctions, it has “plummeted,” as has the currency.

Ansari, however, told Straw that his “strategy of change of regime behavior without accepting what the regime was all about” had not worked. She noted that Iran was, by all accounts, worse off today than it was 40 years ago, when the 1978-79 Revolution took place.

“The slogans are now not against this faction or that faction,” but “to get rid of a system,” she said, referring to the demonstrators in Iran. “Everyone wants regime change.”

Vakil concurred that “things have gotten worse, not better, in 40 years,” and that the Islamic Reupblic was “very much to blame, if not the principal problem.”

But she said the solution was not another revolution.

What was urgently needed, she said, was “much more engagement” on the part of the international community and of Western governments for the situation to improve.

Photos: Leila Mansouri./