By Nazanine Nouri

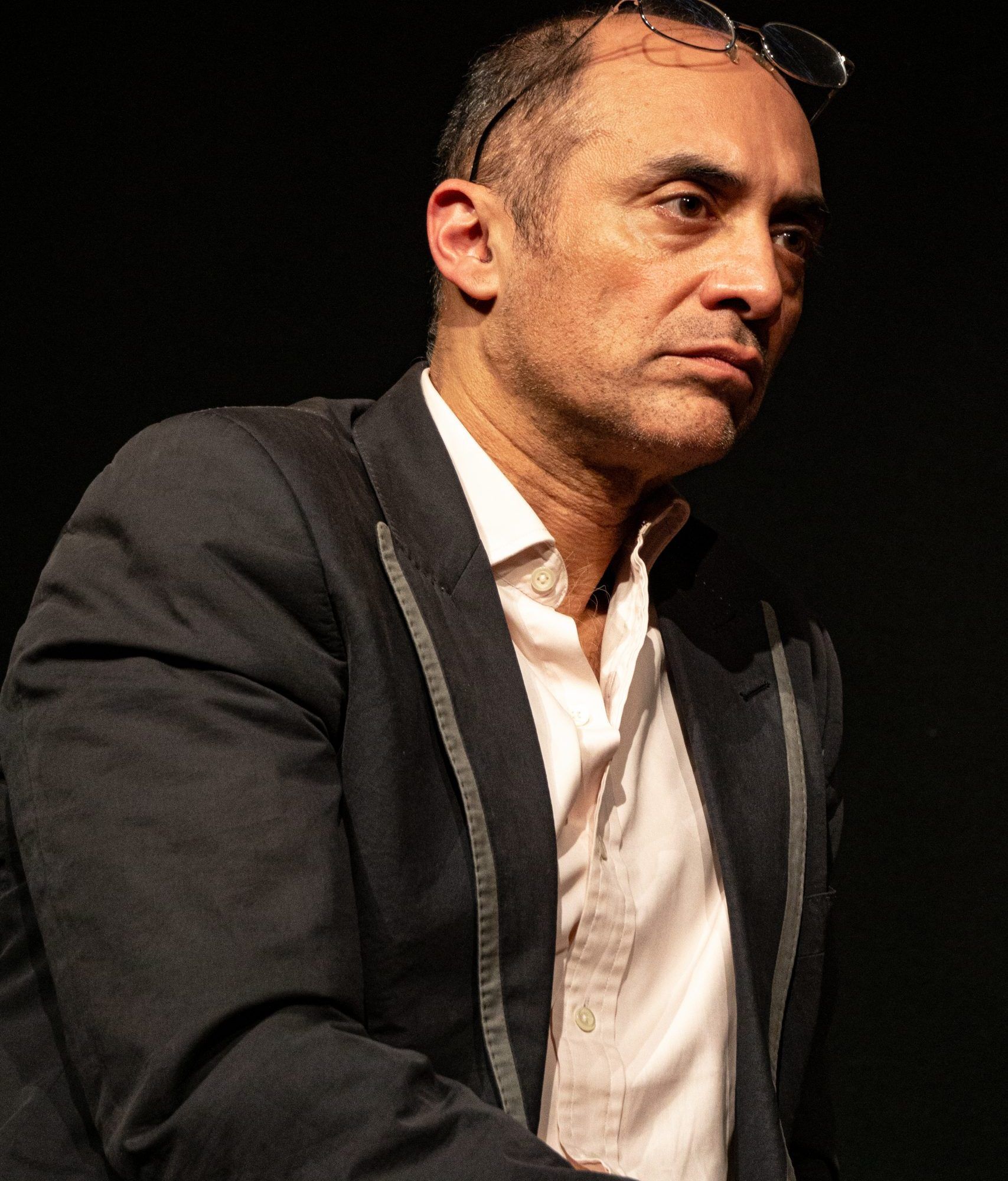

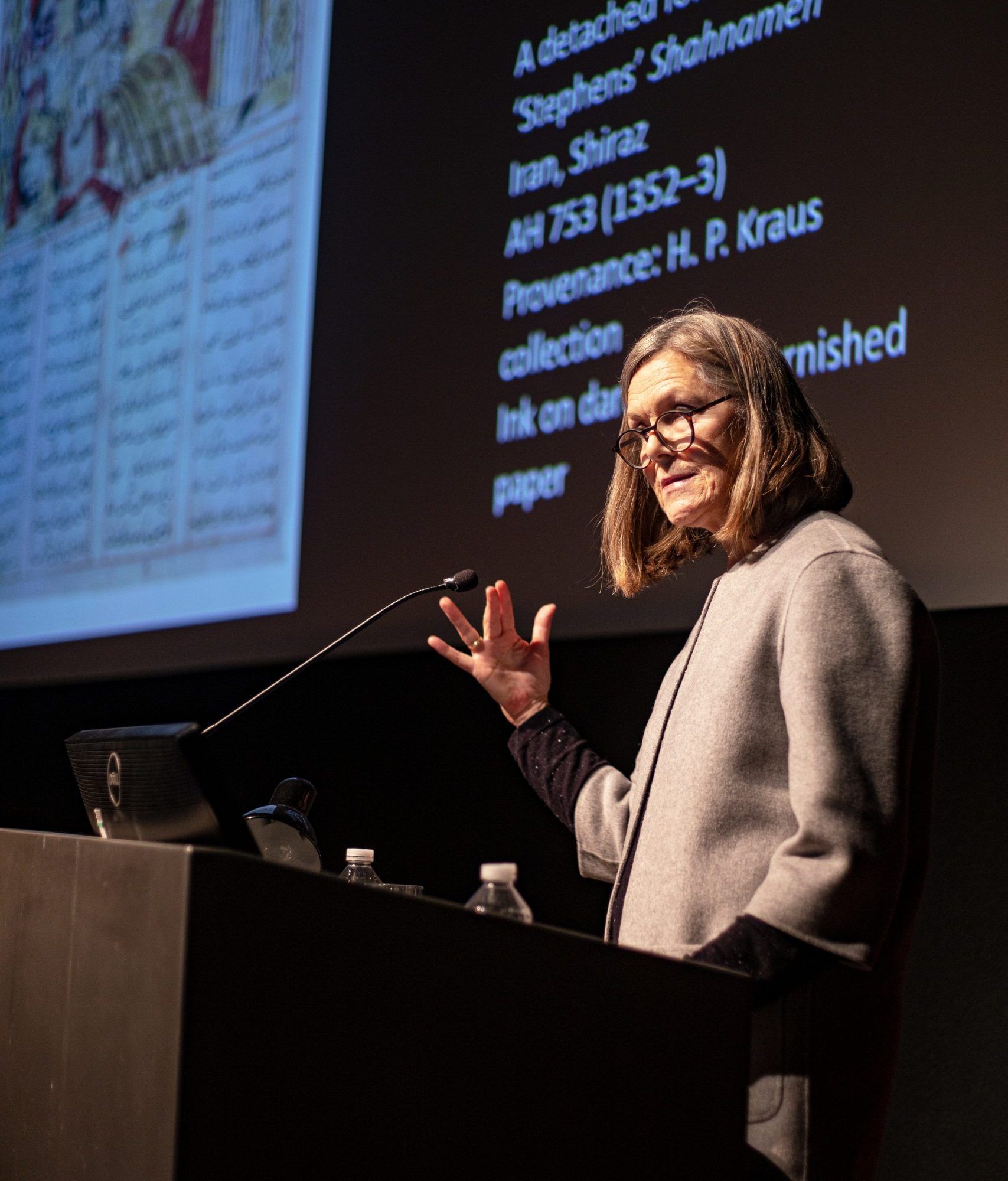

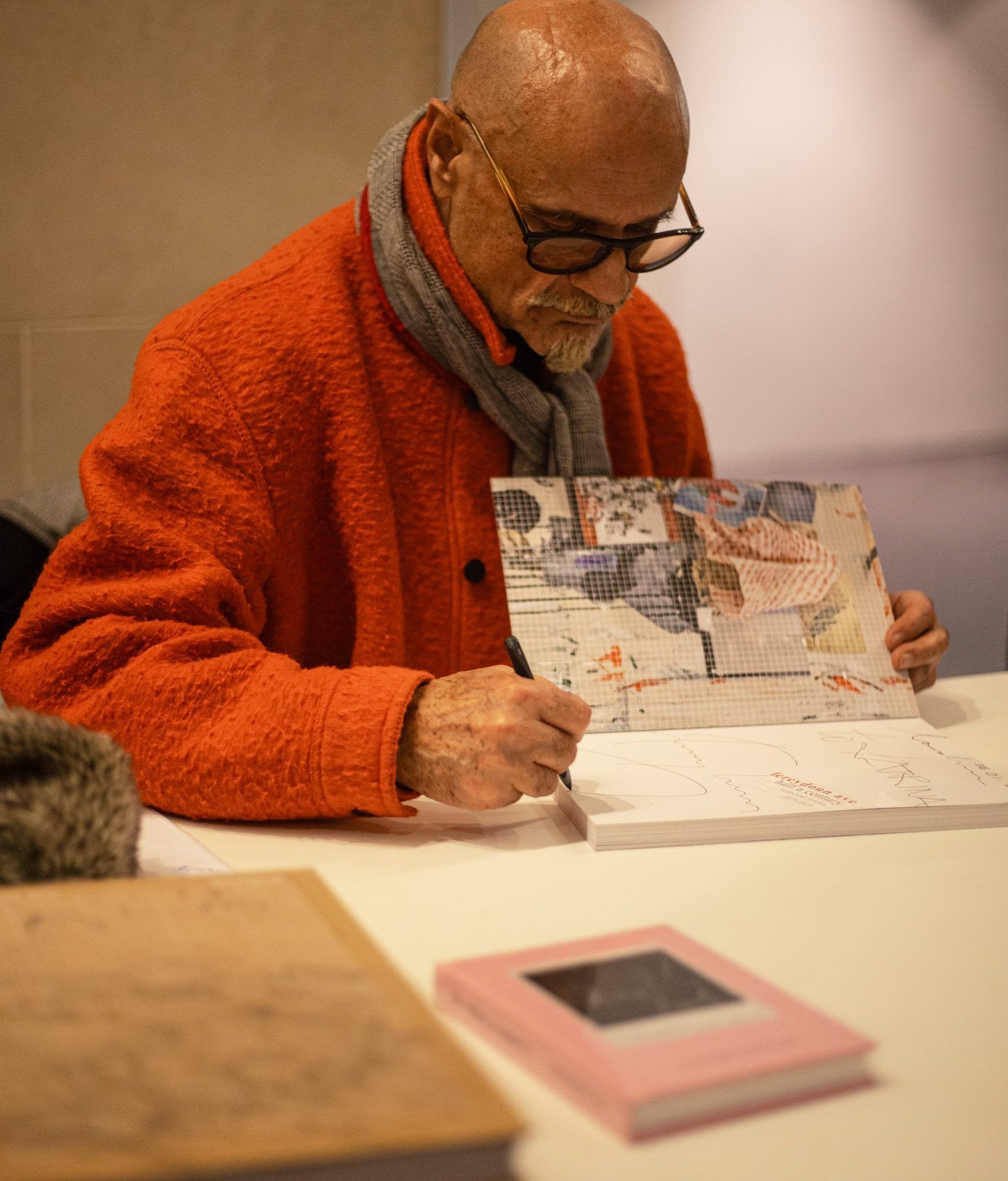

The British Museum recently hosted an afternoon of discussions and screenings focusing on the prominent Iranian artist, curator and collector Fereydoun Ave, who was the key speaker at the event. Introducing the speakers inside the main auditorium was Venetia Porter, associate keeper of Islamic Art at the British Museum. Other panelists were Sarah Stewart, Vali Mahlouji and Hormoz Hematian.

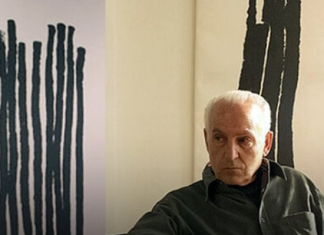

Ave took the opportunity to talk about his art. He described it as being “organic” and coming from within. He discussed his Zoroastrian origins, and said that while he had never really studied the religion, it, too, was an element of his identity that sprang from inside him.

He spoke highly of the Shiraz Festival of the Arts — an avant-garde theater festival launched by Empress Farah in 1967 which featured musicians, actors and performers from around the world. He described it as a meeting place of East and West.

Mr. Ave has occupied a central position in the Iranian art community in the past 50 years. He now divides his time between Paris, Tehran, and countless other locations where he curates and advises artists. A father figure to a host of young aspiring Iranian artists, he says one of the reasons that he stays in Iran is that he makes a difference.

“There is a certain continuity in me that I think post-Revolution artists need to see because they’re all looking,” he told AsiaArtPacific in a 2017 interview. “They feel like orphans – they’re looking for continuity because they were all born out of this schism, out of this void and I treated artists the way I wanted to be treated when I was a young artist.”

Ave was born in 1945 to parents of Zoroastrian origin. His family came from the city of Yazd — a city located on the Silk Road in central Iran and known for its carpets, kilns, silk and velvet fabrics. Young Fereydoun’s father was part of the Zoroastrian community that had moved to Bombay as merchants, and the little boy was surrounded with fabrics growing up.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/2008-11-06T120000Z_1873664616_GM1E4B60QTF01_RTRMADP_3_IRAN-INVESTOR.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”The wind towers from old houses are pictured in the skyline of Yazd, 700 km (435 miles) south of Tehran. REUTERS./” align=”center” lightbox=”off” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Ave lost both his father and grandfather at a very young age and was sent to boarding school in England when he was eight. At 18, he moved to the United States where he received his B.A. in Applied Arts for Theater from Arizona State University. He also studied film at New York University with Martin Scorsese, among others.

“That was an incredible period,” he said in the ArtAsiaPacific magazine interview. “I mean 1969-70 in New York with Andy and the whole underground film thing and being at NYU at that time and space.”

Ave returned to Iran in 1970 where he participated in the country’s burgeoning cultural scene, working as a stage and graphic designer at the Iran-American society in Tehran, as resident designer for the National Theater and as advisor to National Iranian Television and to the Shiraz Festival.

Between 1972 and 1979, Ave was also the acting artistic director of the Zand Gallery, a pioneering space launched by Homa Zand, which hosted exhibitions by the likes of Iranian modernists Leyly Matine-Daftari, Manoucher Yektai or Ghasem Hajizadeh, alongside such internationally renowned artists as Andy Warhol, David Hockney or Claes Oldenburg.

Ave remained in Iran after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, when the Iranian art scene was turned upside down, and committed himself to art creation with determination. “With the revolution,” he said, “one wasn’t sure what you could or couldn’t do and how much freedom of expression you could have as an artist because nothing was clear or written down in black and white. You had to play it by ear and everything would change from one week to the next. It is still changing.”

In 1984, he established Tehran’s first alternative art space on 13 Vanak Street, launching the careers of many of Iran’s most celebrated artists of today, like Farhad Moshiri and Shirin Aliabadi.

Ave said he had empathy for young artists and decided to use the various spaces he had at his disposal for experimentation and for young artists who were simply not commercial. “They were just trying to experiment and learn,” he says. “We had no specific hours, no openings, no invitation cards. People would come and show me their work and if I felt it would add to the experience of other young artists or just present art as an experience within itself, as opposed to a commercial process or a political message, I would say OK we’ll do it.”

As an artist, Fereydoun Ave often refers to himself as a collagist. He works with mixed media in a pop-influenced aesthetic rooted in traditional Middle Eastern elements. His work focuses particular attention on cultural stereotypes that are steeped in Persian history and mythology while at the same time reflecting and responding to sociopolitical events and changing global cultures.

Ave believes one of his greatest influences was his friendship with the late American artist Cy Twombly (1928-2011), who was also his mentor, and who, like him, moved between various worlds and cultures.

His iconic “Rostam” series are mixed media collages depicting the Iranian hero Rostam (a character drawn from the Persian poet Ferdosi’s 10th century epic Shahnameh or Book of Kings) and explore masculinity and virtue in Iranian culture. He represents the mythological hero using a found magazine clipping of a modern-day Iranian wrestler from the Zurkhaneh (traditional gymnasium in which wrestling is practiced.) Rostam is said to have practiced wrestling or koshti, a national sport that dates back to ancient Persia.

“Rostam represents all that is chivalrous and mysterious in the word champion and its code,” said Ave in a 2019 interview with Harpers Bazaar Arabia. “With Rostam, known as the ‘champion of champions’ in Iran, I am trying to locate the position of masculinity in the Iranian cultural context. I am examining the trials and tribulations of Rostam in order to uncover a certain code of conduct.”

“Art is not about messages,” he added. “It’s about layers of complexities and contradictions. Artists pose possibilities, not messages.”

Fereydoun Ave’s works have been featured in many solo and group exhibitions in Europe, the U.S. and the Middle East, including “Shah Abbas and his Page Boy” at Rossi & Rossi, Hong Kong (2017); “The Everlasting Flame: Zoroastrianism in History and Imagination” at the Brunei Gallery, SOAS University of London (2013); “Roundabout: Face-to-Face at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Israel (2011); “Gods Becoming Men” at the Frissiras Museum, in Athens (2004); and “Iranian Contemporary Art” at the Barbican Art Gallery, London (2002). His art has been acquired by such prestigious art institutions as the British Museum in London, Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, Cy Twombly Foundation and Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMOCA).

The British Museum panel was organized by Magic of Persia.