By Parisa Hafezi

DUBAI, July 8 (Reuters) – Iran‘s decision to further challenge the United States by boosting its uranium enrichment beyond limits in its 2015 nuclear deal has deepened fears among Iranians that their country will remain in crisis mode over the long term.

The United States’ exit from the pact last year, under President Donald’s Trump’s campaign to squeeze Iran with sanctions, has so far failed to force its clerical rulers to renegotiate.

Iran confirmed on Monday it had enriched uranium to a purity beyond that allowed by the pact. Trump, who ordered air strikes last month only to cancel them minutes before impact, has warned Iran‘s leaders ‘to be careful’. Since May, he has tightened sanctions with the aim of halting Iran‘s oil exports entirely, depriving it of its main source of revenue.

“Yes, life is difficult because of the sanctions. Yes, I think this (nuclear) programme is too costly for Iranian people,” said Firouzeh, 43, a housewife in the city of Babolsar, reached by telephone.

“But no matter what the reason is, I am against my country being attacked,” she said. Like others interviewed, she asked that only her first name be used due to sensitivities.

The confrontation has taken on a military dimension, with Washington blaming Tehran for attacks on oil tankers, and Iran shooting down a U.S. drone, prompting Trump’s aborted strikes.

Iran emerged from years of sanctions under the deal with world powers that curbed its nuclear programme in exchange for access to world trade. But it had barely begun to enjoy any benefits when Trump quit the pact last year, calling it too weak.

The aim of Trump’s “maximum pressure” on Iran is to push its rulers to accept tougher restrictions on its nuclear activity, drop its ballistic missile programme and scale back support for militant proxies in Middle East conflicts.

Prices for basic goods have skyrocketed in Iran and a young population longs for jobs. In April, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) said Iran‘s economy was expected to shrink for the second consecutive year and inflation could reach 40 percent.

“Look at Syria, Iraq, Yemen. These countries are suffering from years of war. I am not a supporter of the Iran regime but sanctions are hurting people, not its leaders,” said Firouzeh.

Prices of bread, cooking oil and other staples have soared. A more than 60% devaluation of the riyal currency has forced some small factories to close down due to scarcity of raw materials and hard currency.

“Life is very expensive. Prices go up almost everyday. My salary is almost $200 and I have two children,” said elementary school teacher Ghorbanali Hosseini in Shiraz city.

“I work three jobs and I still struggle to take care of my family. America should stop hurting Iranian people like me by sanctioning our country.”

Iranian authorities say 15 percent of the workforce is unemployed. Many formal jobs pay a pittance, meaning the actual figure of people without adequate work is probably far higher.

“I want to live a normal life. I have a university degree but I am jobless, hopeless and sad. Now with these tensions, I am even less hopeful and scared,” said Soroush, who blames “Iranian leaders’ confrontational policies”.

Clerical rulers say sanctions will make Iran stronger.

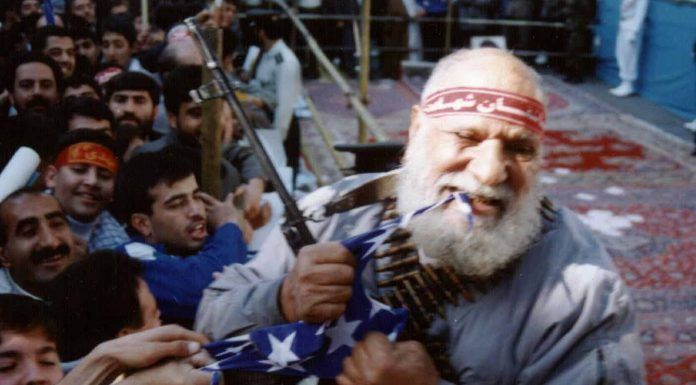

Such rhetoric resonates with some Iranians loyal to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

“We are soldiers of Imam Khamenei and will abide by his orders,” said Hossein Bagheri, 27, a member of the hardline Basij militia in the holy city of Qom.

But many Iranians say they are simply tired of a conflict brought on by the leadership of both countries.

“Political leaders in America and in Iran, I am begging you to let us live in peace. Please,” said Nayerreh Sedaghat, a retired 56-year-old teacher in the southern city of Busher.

(Writing by Parisa Hafezi Editing by Michael Georgy and Peter Graff)