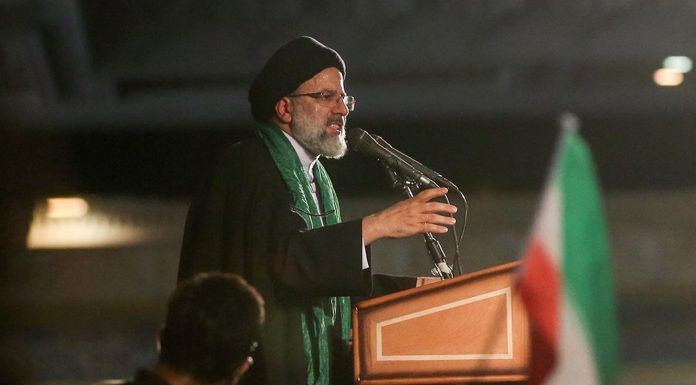

LONDON, March 7 – Hardline cleric Ebrahim Raisi, a protégé of Iran’s supreme leader who helped oversee the execution of political prisoners in 1988, was named chief of the judiciary on Thursday, a job that positions him to undermine the influence of moderates.

Despite his role in executions as deputy prosecutor in Tehran, Raisi’s promotion will make him a contender to succeed Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Raisi, a former presidential candidate who is seen as close to the elite Revolutionary Guards, replaced Ayatollah Sadeq Amoli Larijani.

Also a potential candidate for the supreme leader post, Larijani is accused by rights groups of condoning widespread violations of the rights of political detainees.

The U.S. Treasury imposed sanctions on Larijani last year for human rights abuses. He has said Iran‘s judiciary is one of the fairest in the world.

Appointed by the supreme leader, the head of the judiciary holds significant power in Iran, a country that has long used its powerful legal system to crack down on political dissent.

Iran says its judiciary is independent, and its judgements and rulings are not influenced by political interests.

“Larijani’s work as the head of judiciary was not acceptable,” Iranian Nobel Peace Prize laureate Shirin Ebadi told Reuters.

“But to replace him with Raisi, who had a role in the past in extrajudicial execution and massacre of political prisoners, will taint the judiciary even more … It is replacing bad with worse.”

AUDIO TAPE

Raisi ran in presidential elections in 2017, criticizing pragmatist President Hassan Rouhani for signing a deal with the United States and other powers to curb Iran’s nuclear programme in return for lifting sanctions.

In a fiery election speech, Rouhani accused Raisi of being a pawn of the security services and said Iranians would not vote for “those who have only known how to execute and jail people”.

Raisi’s failure in the elections was widely attributed to a then 28-year-old audio tape which surfaced in 2016 and purportedly highlighted his role in the executions of thousands of political prisoners in 1988.

In the recording, Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, the deputy supreme leader at the time, said the executions included “pregnant women and 15-year-old girls” and were the “biggest crimes committed by the Islamic Republic”.

Montazeri’s son was arrested and sentenced to jail for release of the tape. Raisi prosecuted the case.

Raisi said last year that the trials of political prisoners were fair, and he should be rewarded for eliminating the armed opposition in the early years of the revolution.

“It’s my honour that I fought against hypocrisy,” Raisi said, using a term Iranian officials use when referring to the main opposition groups of the 1980s.

In a report in 2018, Amnesty International said the lowest estimates put the number executed at around 5,000.

“The real number could be higher, especially because little is still known about the names and details of those who were rearrested in 1988 and extrajudicially executed in secret soon after arrest.”

Raisi’s office could not immediately be reached for comment.

AMBITIOUS CLERIC

Although Raisi failed in the 2017 elections, he has remained outspoken, expressing his conservative views on the economy and foreign policy.

Echoing the views of Khamenei, Raisi has said Iran should be self-sufficient in production of essential goods, so it can resist against Western sanctions on its missile programme and regional military presence.

He is currently a member of the Assembly of Experts, an influential clerical body that selects the supreme leader.

“Raisi is in Khamenei’s circle of trust. He has been one of Khamenei’s students and his thoughts are very close to the Supreme Leader’s,” former lawmaker Jamileh Kadivar told Reuters.

Raisi was not well known until 2016 when Khamenei appointed him the custodian of Astan Qods Razavi, a multi-billion dollar religious conglomerate that owns mines, textile factories, a pharmaceutical plant and even major oil and gas firms.

Although some believe Raisi lacks the charisma to replace Khamenei, he shares his deep distrust of the West, limiting U.S. chances of pressuring Tehran to change its domestic and foreign policies if he becomes supreme leader.

RISE TO POWER

Raisi was born into a religious family in Mashhad, Iran‘s second biggest city and home to some of its most sacred sites. He lost his father at the age of five, but followed his footsteps to become a cleric.

As a young student at a religious seminary in the holy city of Qom, he took part in protests against the Western-backed Shah.

After the 1979 Islamic revolution, Raisi’s contacts with top religious leaders in Qom made him a trusted figure in the judiciary. He was deputy head of the judiciary for ten years before being appointed prosecutor-general in 2014.

Last June, Raisi said “internal threats to the Islamic Republic are more dangerous than external threats”, a clear signal that he would not tolerate dissent.

Yet Raisi, a father of two, has in the past surprised many by his unconventional initiatives.

Although his father-in-law, a hardline cleric, banned concerts in the holy city of Mashhad, Raisi met an Iranian rapper during his election campaign and said music can be used to promote religious ideas.

He is also one of the few senior clerics who has publicly spoken about his wife, a university professor, saying women should be encouraged to work and help society move forward.

Larijani’s appointment as the head of the judiciary in 2009 coincided with an uprising in Iran when millions of people came to the streets to protest against the disputed election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the biggest unrest in the Islamic Republic since the 1979 revolution.

Hundreds of protesters, activists, journalists and opposition figures were arrested and put on mass trials shown on state television.

Raisi, then deputy head of the judiciary, defended the execution of a dozen protesters in 2009, saying they were linked to “anti-revolutionary” and “terrorist” groups.

(Reporting by Bozorgmehr Sharafedin Editing by Babak Dehghanpisheh and Giles Elgood)