By John Davison

MOSUL, Iraq, Feb 13 (Reuters) – The wrecks of vehicles used by Islamic State militants as car bombs and other metal debris left by the war in Iraq are now helping fund their Iran-backed enemies, industry sources say.

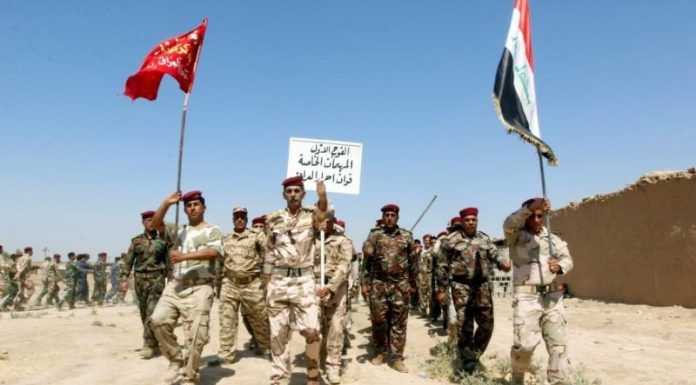

Shi’ite Muslim paramilitaries that helped Iraqi forces drive the Sunni IS out of its last strongholds in Iraq have taken control of the thriving trade in scrap metal retrieved from the battlefield, according to scrap dealers and others familiar with the trade.

Scrapyard owners, steel plant managers and legislators from around the city of Mosul, the de facto IS capital from 2014 to 2017, described to Reuters how the Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF) have made millions of dollars from the sale of anything from wrecked cars and damaged weapons to water tanks and window frames.

The PMF deny involvement. “The PMF does not have anything to do with any trade activities in Mosul, scrap or otherwise,” a PMF security official in Mosul said.

But interviews at scrapyards and with those in the industry corroborate accounts by lawmakers that the militias oversee or direct the transport of scrap, which is then melted down for use in building materials, and turn a large profit.

These sources say PMF groups use their growing influence — and sometimes, according to some witnesses, intimidation — to corner the market and control transport of metal from damaged cities such as Mosul to Kurdish-run northern Iraq where it is bought and melted into steel.

Little of that steel is used to rebuild areas devastated by fighting. It goes instead to Kurdistan or southern Shi’ite provinces, they say.

The trade is one way in which Shi’ite paramilitaries, which are now part of the Iraqi security forces, are transforming their control of land that used to be the IS “caliphate” into a source of wealth.

The increasing influence of the PMF umbrella group, whose most powerful factions are backed by Iran, is worrying the United States and Israel as tension mounts with Iran, which is securing its sway over a corridor of territory through Iraq and Syria to Lebanon.

‘I COMPLY – THEY HAVE GUNS’

At a scrapyard last month near a PMF checkpoint on the edge of Mosul, workers sorted through metal from a pile of car parts, electrical generators and crushed water tanks.

The scrapyard owner said PMF groups buy tonnes of scrap each day and sell it in Kurdish areas for up to double the price — or allow traders to do so in exchange for a cut of the profit, for passage through areas they control.

“This yard is controlled by one PMF faction, that one across the road by another,” he said. He declined to give his name for fear of reprisals by militias.

“I’m only allowed to sell to specific traders – they’re either members of the militia or have a deal with them. You can’t get scrap metal through checkpoints without a deal with the PMF,” he said.

Ahmed al-Kinani, a lawmaker representing the political arm of Asaib Ahl al-Haq, a powerful paramilitary group that has 15 seats in parliament, blamed such trade on individuals “who take advantage of the destruction of war.

“The PMF would not accept this. If there are individual, isolated cases, then the state needs to step in,” he said.

But the scrapyard owner, who said he buys scrap for 100,000 Iraqi dinars ($84) per tonne and sells it for 110,000 dinars, said the PMF or traders they work with sell it in Kurdistan for up to $200 a tonne. He said the PMF had taken control of his yard.

“One day two men arrived in a pick-up truck, carrying pistols, and told me to lower the price and sell only to them. I comply – they have guns,” the owner said.

A worker at the scrapyard opposite described a similar system and prices, although he did not mention intimidation.

Inside Mosul, scrap is bought even more cheaply. One boy said he sold for 50 dinars per kilo ($42 per tonne) to a scrapyard at Mosul’s ruined Old City. The site belongs to a PMF group, he and several other residents said.

The yard contained steel rods and roofing from destroyed buildings, and home appliances. The wreckage of car bombs and destroyed vehicles, many of which were taken out of the Mosul area in the months following the battle that ended in 2017, now make up less of the scrap.

In Anbar province, west of Baghdad, drivers and traders said the PMF held a heap of destroyed cars that is visible from the main highway near Falluja, where fighting was intense in 2015.

The traders said the PMF or companies the militias have agreements with hire drivers to transport metal from Anbar province to Kurdistan, or south to Basra.

Alaa, a driver who used an alias, said permission for transporting scrap lay with the PMF. Lawmakers and traders said the PMF sometimes transported scrap more openly in their own trucks. Reuters could not verify this.

STEEL FROM THE “CALIPHATE”

The volumes of scrap being moved have reduced since the immediate aftermath of the war with IS, but millions of tonnes of debris, including metal, still litter devastated areas.

Mohammed Keko, the manager of a steel plant near Erbil in the Kurdish region, said he had purchased a minimum of 300 to 400 tonnes of mainly Mosul scrap each day since the city was recaptured from IS.

“At the moment we buy for $150 to $160 per tonne. It depends what traders have to pay for it,” he said.

Keko said the PMF controlled transport of scrap, which sometimes was halted for months while militias disagreed on prices or traders could not pay enough to get cargo through.

The steel construction rods that Erbil Steel Co makes from scrap are sold partly in the Kurdistan region but mainly in southern Shi’ite provinces of Iraq, Keko said.

Nawfal Hammadi al-Sultan, governor of Nineveh province where Mosul is the capital, also said the PMF buy scrap but dismissed allegations by some local lawmakers that he allows the paramilitaries to control the trade.

“They buy it (but) there’s no law that forbids anyone to buy scrap metal,” he said.

Lawmakers say the steel should go back to the Sunni areas recaptured from IS to help reconstruction. They partly blame the removal of scrap metal for sale or use in other provinces for the slow pace of rebuilding.

“It’s stealing material that belongs to the state or people,” said Mohammed Nuri Abed Rabbo, a former member of parliament. “The PMF make double whatever they or their traders buy the scrap for. We’re talking hundreds of thousands of tonnes.”

(Reporting by John Davison; additional reporting Kamal Ayyash in Falluja, Ahmed Rasheed in Baghdad, Editing by Timothy Heritage)