By Azadeh Karimi and Elahe Boghrat

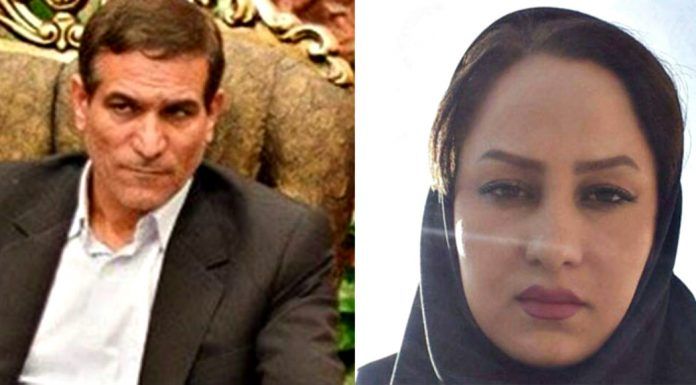

The Iranian media have reported on the suspicious death of Zahra Navidpour, a 28-year-old woman whose body was discovered on January 6 at her mother’s home in the northwestern province of East Azerbaijan. Ms. Navidpour had filed a criminal complaint against Salman Khodadadi, an influential 56-year-old Majlis (Iranian Parliament) deputy, accusing him of sexually assaulting and raping her over a four-year period.

Mr. Khodadadi has represented the Malekan District in East Azerbaijan, in the 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, and 10th Parliament. He is also the chairman of the Majlis’ Committee on Social Affairs, and a former commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) in Ardabil, East Azerbaijan.

Authorities released Khodadadi on September 23 after he posted $48,000 in bail. The East Azerbaijan prosecutor’s office announced on January 6 that it had stopped its investigation into the charges because of lack of evidence.

Other women have in the past accused Khodadadi of sexual misconduct and rape. Navidpour’s body was taken out of the morgue in East Azerbaijan by unknown individuals and buried during the night in the village of Tazeh Qaleh before the coroner could perform an autopsy.

In her video testimony, Navidpour alleges that Khodadadi sexually assaulted and raped her after she went to his office on Valiasr Street in Tehran four years earlier.

In 2009, Massoud Pezeshkian, a Majlis deputy representing Tabriz, capital of the northwestern province of West Azerbaijan, helped Khodadadi maintain his seat in parliament despite being under investigation by the authorities for allegedly raping his secretary and another woman. According to Navidpour, two other residents of Malekan accused Khodadadi of rape, but fearing for their lives, did not filed charges against him.

Navidpour, however, did not stay silent. She filed a series of complaints with Majlis’ Department of Internal Affairs, the all-female parliamentary group Women’s Fraction, the Supervisory Committee of the Majlis, Malekan Prosecutor’s Office, the Malekan branch of IRGC’s Intelligence Organization and the Tehran Prosecutor-General.

Navidpour also wrote to the Speaker of the Majlis Ali Larijani, to the Second Deputy of Parliament Ali Motahari, to the head of the Women’s Faction Parvaneh Salahshouri, and to a deputy representing Tehran Mahmoud Sadeghi, informing them of the alleged crimes committed by Khodadadi. The mail exchanges between Navidpour and the parliamentarians show a reluctance on their part to take action against one of their own, despite the existence of an audiotape on which Khodadadi could allegedly be heard threatening Navidpour and also admitting, at least five times, to raping her.

Navidpour spoke about her ordeal with the Human Rights Activists News Agency (HRANA) in June 2018 on condition of anonymity. She also talked to the Chicago-based Azeri-language Gunaz TV in October. It is unclear whether Navidpour contacted the media inside Iran. However, their coverage of Khodadadi’s arrest in 2009 on charges of sexual assault and rape brought against him by two women shows a reluctance by the domestic news outlets to pursue the story. The print and broadcast media inside Iran have no interest in investigating Navidpour’s allegations against Khodadadi, even after her suspicious death.

After the news media reported on Navidpour’s horrifying experience, people close to him pressured her to withdraw her rape allegations against him in a court of law. She told HRANA that Khodadadi had even accused her and Saleh Rahmati, a senior IRGC commander, of conspiring against him by fabricating the rape charges to damage him politically. Fearing for her life, Navidpour had changed residences a few times. She spoke to HRANA on October 23 for the last time asking the organization to contact her mother if she were to disappear suddenly.

The Iranian Judiciary routinely treats victims of sexual assaults and rape as criminals. The suspicious death of Zahra Navidpour and the subsequent cover-up by the authorities is the latest example of a series of sexual crimes committed against women by men who continue to victimize others with impunity. The tragic execution of the 26-year-old Reyhaneh Jabbari is another example that exposes the misogynist nature of the Islamic Republic and its judicial system. A criminal court found Ms. Jabbari guilty of murdering her assailant and hanged her in 2014 after she spent seven years in jail.

The Islamic Republic treats women as second-class citizens. The civil and criminal laws don’t provide equal rights and protection to the female population of Iran. Authorities rarely investigate the rape and assault allegations and instead treat the female victims as criminals. The Judiciary is hesitant to arrest and prosecute the accused, especially if they are influential men with powerful connections.

There is also a stigma attached to the victims of assault and rape. The subject is taboo in many religious and traditional families, who prefer to suffer in silence rather than speak about a loved one who has been the victim of sexual violence. Many people are unwilling to discuss the issue, even if the judicial system were to provide adequate protection to women. The regime brutally silences courageous women such as Zahra Navidpour and Reyhaneh Jabbari who dare to confront their assailants.

The Islamic Republic misses no opportunity to lambaste the West for exploiting women. It, however, would not hesitate to use women to further its political agenda, a case in point being the late Mohsen Hojaji’s family, who the state refers to as the “family of the martyr” and the “wife of the martyr.” Mr. Hojaji was a 26-year-old IRGC fighter who was captured by ISIS (the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) in the summer of 2017 in Syria. A graphic video of his inhumane and brutal beheading, released by ISIS, went viral on social media and received widespread condemnation.

The regime considers the female population as a commodity. However, it is not men who own women in the Islamic Republic, but rather a patriarchal religious culture which has devoured people irrespective of gender. The regime views anything that falls outside the rigid Islamist doctrine as a threat.

Despite the Islamic Republic’s best efforts to subjugate and oppress the female population in the past four decades, Iranian women have refused to remain victims, and continued to challenge the establishment. It is not in the state’s best interests to recognize the civil and legal rights of Iranian women. Even the all-female Women’s Faction of the Majlis has kept silent about the recent cases of sexual abuse and rape. Whether the regime violates or acknowledges the civil and legal rights of women, they will continue to be a costly problem to the Islamic Republic.

Translated from Persian by Fardine Hamidi