By Amir Taheri

When writing of non-Western societies in the past century or so, many Western European and North American historians and chroniclers adopt one of two attitudes.

The first attitude could be described as “the Imperialism of arrogance.” Here, we are told that whatever good that has happened in non-Western societies is due to the generous action of Western powers whose mission was to export “civilization” to “backward societies.” The people of those societies, referred to as “natives,” could not have done anything good on their own.

The second attitude — which we will call the “Imperialism of guilt” — claims that whatever bad happened to the “natives” was the fault of the Western colonial and/or imperialist powers. On their own, the “natives” could never do any harm to themselves.

For decades, the debate on Iran in the United States and Western Europe has been dominated by “the Imperialism of guilt.” At the heart of this is a legend in which an elderly aristocrat plays the central role. The legend is that in August 1953, a couple of CIA operatives organized a coup d’etat that toppled a democratically elected government and paved the way for the seizure of power by the mullahs 26 years later. The hero of the legend is one Dr. Muhammad Mossadegh who had been appointed Prime Minister by the Shah for a second time in 1952.

The legend was born almost a decade after the events, when the CIA, its reputation in tatters after the Bay of Pigs fiasco, was desperately looking for some success story.

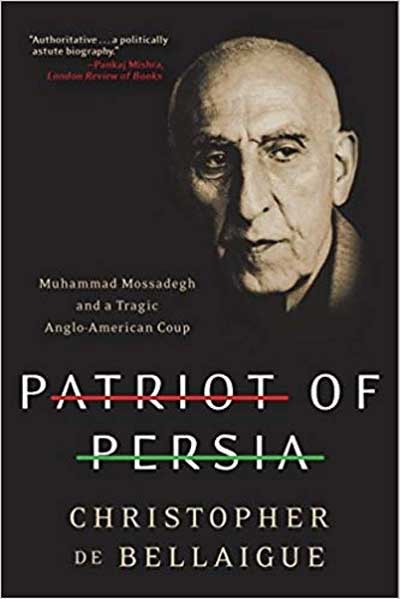

However, the British intelligence service would not let American operatives claim all the glory. “Patriot of Persia,” the biography of Mossadegh by Christopher de Bellaigue (published in 2013), tries to satisfy both sides. The American edition of the book includes, in its subtitle: “A Tragic Anglo-American Coup.” The British edition, however, has a subtitle with the words: “A Very British Coup.”

According to the legend reported by De Bellaigue, the point man for the coup was one Kermit Roosevelt who was a genius in black arts. He arrived in Tehran on 19 July and overthrew Mossadegh just a month later before travelling to have lunch with Winston Churchill in London. To assist him in the adventure, the CIA had a few assets, including the New York Times reporter Kenneth Love and an unnamed UPI stringer of Iranian origin.

Mossadegh’s Iranian opponents get a thorough thrashing from De Bellaigue. While Mossadegh’s supporters are described as “the people” or “popular masses,” his opponents are labelled as “slum-dwellers and trash, rising against a Cabinet of ministers with French Ph.D.’s.” Since the overwhelming majority of Iranians didn’t have French Ph.D.’s, they should have refrained from quibbling about any aspect of Mossadegh’s bizarre leadership.

De Bellaigue cannot imagine that at least some ordinary Iranians might have disliked Mossadegh. Only “goons and mobsters” marched against the “Doctor,” he says. When they burn buildings and shops, Mossadegh’s supporters are merely “showing popular anger.” Yet when Mossadegh’s opponents march against him, De Bellaigue calls their action “sedition.”

Dr. Mozaffar Baghai-Kermani is described as “a young nationalist.” But when the same Baghai turns against Mossadegh, he gets a different adjective: “rabble-rouser.” (In fact Baghai was Professor of Logic at Tehran University, a Member of Parliament, and, above all, a highly respected intellectual).

Mercifully, the Mossadegh legend is as full of holes as Swiss cheese.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Amir-Taheri_1.jpg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” caption=”Amir Taheri” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Let’s start with the claim that prior to the supposed CIA intervention, Iran had been a democracy.

The truth is that Iran was not a democracy, but a constitutional monarchy in which the king, known as the Shah, had the right to appoint and dismiss the prime minister. By 1953, the Shah, who had acceded to the throne in 1941, had appointed and dismissed 10 prime ministers, among them Mossadegh, who was appointed and dismissed twice. And between 1953 and 1979, when he left for exile, the Shah appointed 12 more. None of those changes of prime minister was described as a coup d’etat, because they were fully constitutional and did not alter the substance or the form of Iran as a nation-state.

Interestingly, Mossadegh himself never challenged the Shah’s right to dismiss him as prime minister. During his trial, as De Bellaigue shows, he claimed that he had initially doubted the authenticity of the Shah’s edict dismissing him. Nor did Mossadegh himself claim that the Americans had played a role in ending his tenure as prime minister.

De Bellaigue is at pains to portray Mossadegh as “one of the first liberals of the Middle East, a man whose conception of liberty was as sophisticated as that of anyone’s in Europe or America.” The problem is that there is nothing in Mossadegh’s half-century career as provincial governor, cabinet minister and finally prime minister to qualify him even remotely as a liberal in the generally accepted sense of the term.

Here is how De Bellaigue quotes Mossadegh himself describing the ideal leader: “that person whose every word is accepted and followed by the people.”

De Bellaigue adds: “His understanding of democracy would always be coupled by traditional ideas of Muslim leadership, whereby the community chooses a man of outstanding virtue – and follows him wherever he takes them.” That could be the definition of “the ideal leader” by the late Ayatollah Khomeini, who would have felt insulted had he been described as a democrat.

During his premiership, Mossadegh demonstrated his authoritarian character to the full. Not once did he hold a full meeting of the Council of Ministers, ignoring the constitutional rule of collective responsibility. He dissolved the Senate, the second chamber of the Iranian parliament, and shut down the Majlis, the lower house. He suspended a general election before all the seats had been decided and announced that he would rule by decree. He disbanded the High Council of the National Currency and dismissed the Supreme Court. Towards the end of his premiership, almost all of his friends and allies had broken with him. Some, like veteran parliamentarian Abol-Hassan Haeri-Zadeh, even wrote to the Secretary General of the United Nations to intervene to end Mossadegh’s dictatorship.

During much of his premiership, Tehran lived under a curfew, while hundreds of opponents were imprisoned.

Was Mossadegh “a man of the people” as De Bellaigue claims? Again, his account provides a different picture.

A landowning prince and the grandson of a Qajar king, Mossadegh belonged to the so-called 1,000 families who dominated and owned Iran. He and all of his children were able to undertake expensive studies in Switzerland and France. The children had French nannies and when they fell sick would be sent to Paris or Geneva for treatment. On the one occasion that Mossadegh was sent into internal exile, he took with him a whole retinue, including his special cook.

Dean Acheson described Mossadegh as “a rich, reactionary, feudal-minded Persian inspired by a fanatical hatred of the British.”

Even his supposed hatred of the British is open to question. His uncle, the Qajar Prince Farmanfarma, was Britain’s principal ally in Iran for almost four decades. In his memoirs, Mossadegh says that in his first post as Governor of the southern province of Fars, he and the British consul “worked hand in hand like brothers.”

As a model of patriotism, too, Mossadegh is unconvincing.

According to his own memoirs, at the end of his law studies in Switzerland, he decided to stay and acquire Swiss citizenship. He changed his mind when he was told that he would have to wait 10 years to obtain that privilege. At the same time, his uncle Farmanfarma secured a post for him in Iran, tempting him back home.

The claim that Mossadegh was a secular liberal is further shaken by several of his most notorious statements. De Bellaigue quotes him as saying that anyone forgetting Islam was “base and dishonorable and should be killed.” His close association with Islamists, including the Fedayeen Islam who assassinated his predecessor as Prime Minister, General Haj-Ali Razmara, was a source of concern for many of Mossadegh’s supporters.

Mossadegh’s claim in his memoirs that he saw “a celestial figure,” presumably the Hidden Imam, in a dream inviting him to ”break the chains of Iran” is a curious indication of his mindset.

Mossadegh’s name is associated with the nationalization of Iranian oil in 1951. However, he was not even a member of the parliament that passed the nationalization act. The bill was drafted by five MPs, all of whom backed Mossadegh after he had been appointed Premier and, two years later, broke with him. The Shah appointed him Prime Minister to implement the oil nationalization act but, plagued by indecision and always prey to the demons of demagoguery, Mossadegh failed in that mission.

De Bellaigue tries to build the 1951-53 drama in Iran as a clash of British colonialism and Iranian nationalism. However, that claim, too, is hard to sustain. Iran was never a British colony. The Anglo-Iranian Oil Company was present in five remote localities that did not amount to even half of one per cent of the country’s huge territory. At its peak the company employed 118 British nationals, most of them Indians of Sikh and Muslim origin acting as guards or domestic servants. Thus, the overwhelming majority of Iranians had never seen a single Briton in their lives. However, De Bellaigue labels Iranians as “natives” or “Orientals” facing “the white world.” (Iranians, of course, do not consider themselves as “blacks” or even worthy oriental gentlemen! They think they are Aryans and thus of a superior stock than the British).

De Bellaigue cannot believe that Mossadegh’s Iranian opponents may have had views and policies of their own. He writes: “Opposition MPs had been encouraged by the CIA to dispute the legality of the referendum” that Mossadegh launched without going through the legal process.

He says that Mossadegh’s opponents “raved” while the Doctor “reasoned.” Street demonstrations by Mossadegh’s supporters are described as a “show of popular anger.” But the same done by his opponents is labelled “sedition,” a religious term.

At times, De Bellaigue labels the dismissal of Mossadegh as “a military coup,” forgetting that no military units were involved in the street demonstrations that forced the Doctor to go into hiding. At that time, Mossadegh was Minister of Defense and had declared himself Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces. One of his relatives, Brigadier-General Taqi Riahi, was Chief of Staff, and another relative, Brigadier-General Muhammad Daftari, headed the National Police. The nation’s coercive forces and their equipment were under Mossadegh’s exclusive control. The man chosen by the Shah as successor to Mossadegh as prime minister was Fazlollah Zahedi, a retired brigadier-general who had gone into hiding after Mossadegh set a price on his head. Zahedi didn’t reappear until after Mossadegh had gone into hiding and the uprising against him had succeeded.

De Bellaigue speaks of the events as “a plan to restore the Shah.” But the Shah hadn’t abdicated, nor had he been deposed, to need restoring. Mossadegh stubbornly refused to declare the end of monarchy and cast himself as president of a putative republic.

The old Qajar prince had a playful approach to everything; his first priority seemed to be amusing himself. He received foreign dignitaries lying in his bed and pretending to be unwell. According to De Bellaigue, during his trial Mossadegh challenged the Prosecutor, General Azmudeh, to a wrestling match. “If I don’t win, cut my head!”

But why did the Americans who had consistently supported Mossadegh for almost three years suddenly decided to get involved, as De Bellaigue claims, in a plot to remove him from office?

Here is de Bellaigue’s answer: In the U.S., “under Republicans, fair play had gone by the board at home, where Senator Joe McCarthy was directing a persecution of suspected Communists. It was a good moment for a muscular assertion of American values abroad.”

De Bellaigue describes President Dwight D. Eisenhower as a “gloves-off Cold War warrior.” The Dulles Brothers, John Foster and Allen, respectively Secretary of State and head of the CIA, were “a pair of wartime spies” who wanted to blacken Mossadegh’s name as a tool of the pro-Soviet Tudeh (Communist) Party. A bit too thin as a motive, you would admit.

Mossadegh’s career spanned more than half a century. History may end up seeing him as a spoiled child who refused to grow up. His brand of negative populism may have been attractive many decades ago. Now, however, it sounds bizarre, to say the least.

The legend of the “American coup against Mossadegh” is so firmly established in many political and academic circles that any critique of it is regarded as sacrilegious. One veteran propagator of the legend, Professor Ervand Abrahamian, a distinguished Iranian-American academic, recently lamented the fact that after having spent “40 years of my life” trying to blacken the name of the Shah and his father, he now witnessed Iranians taking to streets calling for the ghost of the Shahs to return!

Maybe the Shah’s dismissal of Mossadegh, the so-called “August coup” known in Persian as “28 Mordad,” was a mistake. But the events that led to it did not constitute a coup d’etat in the proper political sense of the term — look it up in any dictionary! At most it may be described as a putsch, the removal from office of one faction within the ruling establishment by another.

Maybe Mossadegh was the best thing humanity had seen since sliced bread. But the fact is that he turned everyone against himself and failed to offer any strategy to lead Iran out of the crisis. The Shah, who knew Mossadegh well, could be criticized for having appointed him as prime minister in full knowledge that the old “Doctor” was a charismatic opposition leader but a poor leader of government. The old “Doctor,” an egomaniac prince at heart, simply had no time for bureaucracy, reading papers, attending meetings, negotiating, solving problems etc.

De Bellaigue writes: “Without the fall of Mossadegh, Iran’s history would have been happier.” Maybe. Some may say it would have been happier without his mistakes.