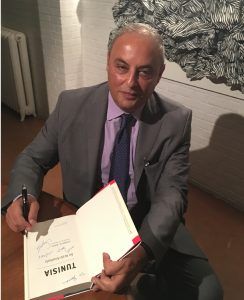

Safwan Masri’s “Tunisia: An Arab Anomaly”, explores the key ingredients which helped Tunisia transition from authoritarian rule to peaceful democracy. The book charts the Arab Spring, which began in 2011, and also looks at Tunisia’s roots, as well as the role of Islam in shaping the country. In the book, Professor Masri argues that Tunisia’s path to peace cannot be used as a role model for other Arab countries, because its revolution was unique, and many centuries in the making.

Professor Masri is the Executive Vice President for Global Centers and Global Development at Columbia University, and is also a Senior Research Scholar at Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs.

His interests include education and contemporary geopolitics and society in the Arab world. In his book, “Tunisia, An Arab Anomaly”, Professor Masri looks at the Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia, and makes a compelling case for education as the root cause of the country’s successful transition to democracy in the twenty first century.

Kayhan Life spoke with Professor Masri about his book, and the implications that the Jasmine Revolution might have for non-Arab countries, like Iran.

Professor Masri, thank you for speaking with us.

Why did you decide to write about the Jasmine Revolution?

It was not a conscious decision, I was fascinated with what was going on in Tunisia and the state of the Arab world. With the advent of the Arab Spring, I was struck by how differently things were developing in Tunisia in contrast to other Arab countries, and led by a professional and a personal curiosity, I wanted to understand these developments.

Which moment for you personally represents the tipping point of the revolution?

There were several precursors to the revolution which led up to a tipping point. I talk in the book about those precursors, including the riots in 2008, which were suppressed by President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, the corruption within the Ben Ali regime and of course the ouster of Ben Ali, as just a few examples. To my mind, the tipping point itself was in 2013, when the then-Islamist Ennahda government agreed to resign following the assassinations of Tunisian opposition party leaders Chokri Belaid and Mohamed Brahmi, and that really was a major tipping point because things could have fallen apart and led to a civil war. Instead, the resignation led to Tunisia moving in a positive direction.

In your book you say that education underpinned the success of the revolution in Tunisia. What element or elements do you feel are now important to the country’s future success?

A major stressor on Tunisia today is its economic situation, so I think economic reform and greater investment in the country are really important for it to build upon its success. There are also other elements within the country that need to be preserved going forward. I worry that the government could gain more control over international civil society organisations within the country, and I think that would be to the detriment of Tunisia’s transition towards democracy. There needs to be a preservation of the independence of civil society, and activism within civil society; these are incredibly important areas. Similarly, the continuing path towards further emancipation of women, and other minorities in the country has been a major factor in the country’s development, and that seems to be continuing on the right track. Freedom of expression is also vital. I believe that all these elements are the most fundamental ones and will keep the country on its current trajectory.

How important was social media in mobilising Tunisians and what tactics did the Tunisian government use to try to stop or censor Tunisians online?

Social media played an important role, though it was not as pronounced as the West often considers it to have been. It did highlight and helped disseminate important events though, such protests, and afterwards, the dismantling of statues. These are examples of events which garnered wide exposure and were important in getting people galvanized and organized. Of course the distribution over social media of images of Mohamed Bouazizi’s self-immolation, which triggered protests, was momentous.

However, when looking at events leading up to the revolution, I think social media played a critical role. We have to remember that under Ben Ali’s government, Tunisia was the first country in the Arab world and Africa to get connected to the internet, but it was very tightly controlled by the government as well.

Around the time that Wikileaks emerged, there was heightened internet use amongst Tunisians. As a result, when Wikileaks made people aware of the levels of hypocrisy and corruption within Ben Ali’s government, Wikileaks was of course promptly shut down in Tunisia. In response to this move, the Tunisian diaspora kept the dialog going and the lines of communication open including access to Wikileaks data, which was of course very powerful. To my mind, social media played a very big role in the run up to the revolution in raising awareness of the problems Tunisians were experiencing. During the revolution, its role was mostly in terms of sharing information and images, thus encouraging protestors to follow suit across the country.

You explain that Tunisia’s relatively ethnically homogenous population has helped to bring about social cohesion. Do you think this has to be an ingredient for a successful revolution?

No, I don’t think that’s an essential ingredient. I think the most important ingredients stem around activism and engagement within civil society. So, whilst the relative homogeneity of Tunisia’s population was a factor, I would not categorize it as a decisive factor in the revolution’s success. We also have to remember that Tunisia’s population is not totally homogenous and that there are disparities between the coast and the interior regions, in terms of economic, religious and secular denominations. More important than the issue of homogeneity is the concept of identity. Tunisians have a very strong sense of ethnic and cultural identity, which is underlined by a deep tolerance towards one another’s differences.

An Arab Anomaly explores the impact of uprisings in the Middle East specifically within Arab countries. As a result, the book doesn’t look at internal conflicts within countries like Iran. Do you have any predictions about what you feel may be the end result of the ongoing demonstrations in Iran?

Tunisia is different from Iran in many respects, including that what really helped it was that it was never important from a geopolitical perspective, regionally or globally. For example, Tunisia did not get entangled in the Cold War, or the Arab-Israeli conflict, and so it could maintain a healthy distance from these kinds of tensions. This allowed Tunisia to progress and evolve in a way that did not involve global or regional powers and their ensuing interests.

When one looks at Iran, everything that happens in the country is of course connected to geopolitical factors, so the way, for example, that the Iranian population is dealing with issues that it faces internally are connected to how the West is dealing with Iran. Unlike Tunisia, when you look at dynamics within Iran, those dynamics are very much related to Iran’s actions with the outside world and the impact that has internally within Iran.

Having said that, the longer-term prospects for Iran, I believe, are ones which will lead to an end to the current status quo. I think it’s fair to say that the goals of the 1979 revolution have not been met as far as the Iranian regime is concerned. My prediction is that current government in Iran will unravel, over a period of decades or perhaps years, and that Islamic governance will come to an end, which in a country the size of Iran and one which is so important, will have ramifications for the rest of the world. Iranians are a proud and highly educated people, who rest on thousands of years’ worth of history, which they are acutely aware of. I believe Iranians want to be part of the global community and have social and economic aspirations that can’t be contained indefinitely.

Iranians share many similarities with Tunisians, including pride in education, curiosity, religious tolerance and now, a deeply angry population oppressed by terrible economic conditions, government corruption and human rights abuses. Do you think Iranians could apply the Jasmine Revolution’s mechanics to bring about the peace they want?

There are great similarities in terms of the people, their level of education and civilisation and their rich history, but the institutional set-up in Iran is quite different to Tunisia. In Iran, you have the Revolutionary Guards, state institutions that play a very strong, and in some cases very negative, role. Tunisia, with its small and apolitical army and its secularism since independence, was spared all of that. One could argue that civil society in Tunisia was at times as strong as the regime itself, meaning that the situations in the two countries are quite different. I am hopeful for Iran in the long run, but I don’t believe it will follow a similar path to Tunisia as the dynamics in Iran are quite different and so the resolution and the mechanics of that resolution will also be quite distinct.

You mention that Tunisian youth felt cheated as a result of the economic hardships they faced but were ultimately open to democratic government which balanced Western standards with Islamic ideals. Iranian youth also feel disenfranchized, but some have a cynical view of anything western due to a sour history with meddling countries like the UK and the US, and a growing mistrust of its Islamic leaders. How could Iranian youth mobilize their knowledge and education to carve out an identity of their own?

I’d like to think that Iranian youth have a strong sense of identity that they have inherited and so I don’t think they are struggling as such with finding an identity, but I am fascinated by the way in which Iranians have turned to their pre-Islamic history, since the time that the country was evolving toward a modern nation-state, in a very determined and conscious way. The country has a long and rich history which goes back thousands of years and which appears to make up a large part of the nation’s identity to this day.

The revolution clearly reversed some of that identity, but it is very difficult to completely erase that kind of history, which I believe is deeply rooted in Iranian thought. I think it’s important to have that as a background and to bear in mind that Iranian youth are also conscious of this history and feel connected to it. At the same time, I think they’re looking to balance that legacy with global values, which are not necessarily Western, but perhaps ones which appear to be universal in spirit. I don’t think balancing those two ideals is impossible. Iranian youth want their country to have a seat at the table globally and they want to engage with the world, and so I do not think that they are turning their backs on the West, as much as that might seem to be the case today, especially in the face of increasing Western threats.

Tunisia’s success appears to have been in part due to a strong level of engagement by its women. Are there any parallels between them and Iran’s own vocal women and girls?

Yes, there are. Women everywhere are key to positive transformations, socially and nationally. Iran’s long and rich history has always celebrated women, and today they are amongst the most potent agents of change in the country. Similarly, Tunisian women have always played key roles in their country. They helped lead the revolution, and they continue to contribute to the country’s evolution since the revolution. The main difference, though, is that in Tunisia, women work hard to ensure that the gains they made under authoritarianism are safeguarded, whereas in Iran, women are fighting to restore the liberties they enjoyed before 1979.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Tunisia3.jpg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” caption=”Tunisian lawyers demonstrate against the government’s proposed new taxes, near the courthouse in Tunis, Tunisia December 6, 2016. REUTERS/Zoubeir Souissi” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”inplaceslow” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

You offer the idea that some of the greatest tensions during the most important phase of the revolution centred around a push and pull between those who wanted to break from the past completely and look to a different kind of future, and those that longed for the days as they were, during authoritarian rule. How were those tensions resolved?

Whenever you have a revolution, or an abrupt change of government within a state, you have the counter revolutionary elements and elites who had benefited under the ancient regime and who feel threatened by democratization and the inherent and perceived loss of power and authority. That tension really persisted for a long time, but the solution was carried by the strands of the revolutionary and democratic forces that came to influence the way the country transitioned. Those tensions continue to exist, and you have reactionary forces that are still at play today. For example, tensions within the government, and with civil society and remnants of the old regime trying to regain some semblance of power within the new governmental structure. In reality, these tensions have not been completely resolved but by and large those counter revolutionary forces have been weakened.

You make a strong case in your book that Tunisia has found peace thanks to a nation inherently drawn to a secular, democratic way of life, but your book also mentions that Tunisia is one of the largest exporters of terrorists in the world. How would you respond to critics who take the view that Tunisia’s Arab Spring was not a complete success because its revolution ultimately fractured a nation, with those disagreeing with the new status quo, or perhaps still unable to find work, making homes elsewhere, most notably in the arms of countries practicing political and often deeply violent perceptions of Islam?

Those that did break away and find homes with organisations such as ISIS, are a very small minority. People fled in 2011 and left the country to join extremist forces outside Tunisia, and I talk about this in my book. I mention that during a twenty-year period, we had tens of thousands of fundamentalists who had been imprisoned in the country, and some of them exiled. We know that prisons are recruiting platforms for fanaticism, and when released in 2011, these entered Tunisian society and could not relate to it. Many found Ennahda, for example, too moderate for their views, and many felt a sense of belonging in ISIS. Social factors therefore played a role in the very heavy recruitment of civilians by ISIS, but even then we are talking about thousands, rather than tens of thousands of people.

Poverty was also a factor in ISIS’s uptake, and I mentioned the economic conditions in Tunisia, and I don’t want to undermine that aspect, because as I mention in my book, as long as we continue to neglect the disparity between the coastal region and the central region, and the need to invest in the country, Tunisia will always be susceptible to radicalization, which occurs when people feel socially and economically disenfranchised.

There are fascinating insights in your book looking at how Tunisians tackle extremism in order to stop it advancing during critical periods in Tunisia’s history, and now, to guard against it seeping back into society. Can you tell us about that?

If we broaden the definition of extremism, so that we’re not only talking about extremism in the way we are experiencing it today and over the last twenty years, but rather broaden extremism to include historical acts of power, Tunisians have had a long history of toleration. In particular, Islam evolved inside the country with remarkable deference to existing influences, such as Berber, African, and Christian. Tunisia benefitted from interaction with Southern Europe, influences from Judaism, Christian theology within the early centuries, and then Islam when it arrived, and how it had to adapt itself to local customs and cultures. The country also benefited from interactions with Andalucía, all of these developments were important contextual factors which created a tolerant society.

The most important development in the recent history of Tunisia was its exposure to Europe and ideas of the Enlightenment during the nineteenth century, and how it interacted with Western Influences, negotiating its way with them, and either adopting or rejecting various elements. For example, Tunisia’s abolishment of slavery in 1846 was influenced by a British army officer, Sir Thomas Reade. Noteworthy developments at the time include the 1857 security covenant that gave non-Muslim subjects equal rights and protection under the law. At the heart of Tunisia’s success in stemming extremism is the ability to be tolerant and inclusive.