[aesop_content color=”#ffffff” background=”#333333″ columns=”1″ position=”none” imgrepeat=”no-repeat” disable_bgshading=”off” floaterposition=”center” floaterdirection=”up” revealfx=”inplaceslow” overlay_revealfx=”off”]In less than 20 years, severe water shortage and drought has turned vast regions of Iran into deserts. Many Iranians blame the government for mismanaging crucial environmental problems, including the rapid desertification of large areas that were previously wildlife habitats. The following is a report by the German newspaper Suddeutsche Zeitung’s Middle East correspondent, Paul-Anton Kruger, on the impending ecological disaster in Iran. (It appeared in the July 8 edition of the newspaper.)

[/aesop_content]

“An orange glow envelops the ancient city of Isfahan (capital of the central province of Isfahan) at dusk. The temperature has reached 42 degrees Celsius today. Many families are picnicking in the park near the river. They have taken refuge from the scorching sun under massive trees. They are eating sunflower seeds and drinking sweet tea.

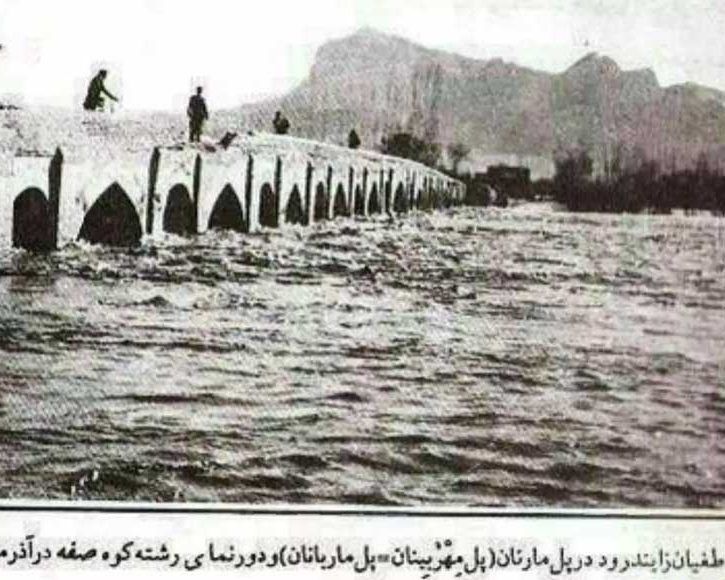

People settled around these river banks more than 2,000 years ago. The Greek geographer and philosopher Strabo (63 BC – 23 AD) mentioned Isfahan in his writings in 20 AD. The mighty Zayandeh-Rud (life-giving river) flows down from an altitude of 4,000 meters on the Zagros mountain range, creating a fertile oasis below.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Zayandeh_rood.jpg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” caption=”Zayandeh-Rud. Source: Wikimedia Commons” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”inplaceslow” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Zayandeh-Rud is 150 meters wide at its widest point near Isfahan, and 11 bridges connect its banks. Old postcards show the iconic Allahverdi Khan Bridge (better known as Si-o-se-pol) built in 1602 AD, towering over the river. In one picture, we see the reflection of the bridge’s 33 massive columns in the water.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Khajou_Bridge.jpg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” caption=”Zayandeh-Rud. Source: Wikimedia Commons” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”inplaceslow” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

No water flows through the two-story stone Khaju Bridge either. In its heyday, Khaju served as a bridge, a dam and a barrier. The stone steps, which for more than four centuries slowed the powerful current, are dried up. All that remains is a scarred and wounded red desert that stretches for kilometers.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/zayandeh-rood6.jpg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” caption=”Zayandeh-Rud. Source: Kayhan London” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

‘Zayandeh is the soul of our city,’ says Hassan Hossein, a 63-year-old retired teacher. Sitting under a big tree with his wife and son, Mr. Hosseini adds: ‘There was a time when the river flowed all year long. However, the riverbed has dried every summer for the past seven or eight years. We still come here to picnic, nevertheless. This place has a special meaning for us. Water shortage is a political issue. We pray to God to solve this problem. Soon we’ll have no water unless the government takes action.’ Nowadays, it’s not just the river that has evaporated: locals face severe water shortage even inside their homes.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/zayandeh-rood7.jpg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” caption=”Zayandeh-Rud. Source: Kayhan London” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Isfahan has become synonymous with water shortage these days. Reza Ardakanian, Iran’s minister of energy and the coordinator of the UN Water Task Force on the planning and organization of the new Water Decade (2018–2028), warned in April: “There are currently 334 cities with a total population of 35 million who face water scarcity. The situation is critical for 17.2 million people in 100 cities, and another 17.3 million are struggling with severe water shortage.” As a water management expert, Mr. Ardakanian is acutely aware of the water crisis facing the country. About five years ago, another government official warned that dozens of Iranian provinces would be uninhabitable by 2025.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/zayandeh-rood5.jpg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” caption=”Zayandeh-Rud. Source: Kayhan London” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Clashes between protesters and security forces over water shortage are a common occurrence these days. Residents of Khorramshahr and Abadan, two of the biggest cities in the southwestern province of Khuzestan, complained about salty and muddy water coming out of their homes’ taps for a few days in April. The main pipeline had burst, contaminating the water supply to the province. Police had used tear gas to disperse the demonstrators. One protester had been shot and injured by the security forces. There were also many street marches in Isfahan over water shortage in 2013 and 2016.

Shortage of rainfall in the past 10 years, mismanagement of the country’s reservoirs and increased consumption due to massive population growth in the last 40 years have contributed to the current water crisis in Iran. The residents of Isfahan and people living along the southern banks of Zayandeh-Rud believe that bad management is the principal cause of the water crisis.

The construction of the Zayandeh-Rud Dam started in the mid-1960s, but it didn’t become fully operational until 1971. Even today, passengers traveling on the Tehran metro can see massive banners depicting the dam as the symbol of progress. It protected the people who lived in the valley below the mountain, when the snow melted in spring, causing the river to overflow. It also provided much-needed water for farmers growing wheat.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/zayandeh-rood1.jpg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” caption=”Source: Kayhan London” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”inplaceslow” overlay_revealfx=”inplace”]

In the 1990s, the government laid down a pipeline that supplied water from Zayandeh-Rud to the desert city of Yazd, 270 kilometers southeast of Isfahan. Using pipes that measured 1.6 meters in diameter, engineers diverted the course of the river, which in many people’s view caused the current water crisis in the province. Angry farmers attacked the pipeline twice in 2013 and 2016, which prompted the authorities to ration the water supply in Yazd.

The city of Isfahan used to provide some of the most fertile fields for farming. The dozen or so pigeon towers along the banks of the Zayandeh-Rud are evidence of a rich agricultural tradition that dates back 300 years. Locals collected and used pigeon droppings to fertilize melon and cucumber fields. The typical pigeon tower is cylindrical and constructed of mud brick, lime plaster, and gypsum. They were impenetrable fortresses that could shelter the pigeons from predators.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/2006-01-11T120000Z_2080718055_PBEAHUNTQAO_RTRMADP_3_ISFAHAN.jpg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” caption=”-PHOTO TAKEN 10JAN06- A general view of the Khagoo bridge on the Zayandeh-Rood river in Isfahan, 450 km (280 miles) south of [Tehran], January 10, 2006. Isfahan was designated ‘Cultural Capital of the World of Islam’ by the Organization of the Islamic Conference for 2006. PICTURE TAKEN JANUARY 10, 2006.” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”frombelow” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

At one point, 2 million people lived and farmed on the banks of the Zayandeh-Rud. Today, travelers walk along barren farmlands. One can see abandoned crops from previous years scattered around the cracked red soil. The surface irrigation network of canals dried up years ago. More than 100,000 people have lost their jobs and livelihoods and migrated from villages to cities such as Isfahan to work as day laborers.

The ditches, canals, and trenches that were used to water the fields have all dried up. The scorching sun and hot wind have eroded the irrigation system. The salt and dust cover the land. In March, thousands of people protested in the Farzaneh region, where Zayandeh-Rud had created an oasis in the Gavkhouni wetland (salt marsh east of Isfahan). They were sarcastically chanting: “Death to farmers, long live the oppressor.”

Reza Khalili, who 17 years ago founded the organization for the protection of the Gavkhouni wetland and the Farzaneh cultural heritage, says: ‘More than 90 percent of the agricultural land will never be farmed again. The odd green patches we see here and there get their water from deep wells. Many of the old wells ran out of water a long time ago. Most of the trees have died as well. There was a time when you could dig a well with your bare hands. The water level has dropped below the 12-meter mark. It has been a long time since the government has allowed anyone to dig a well.’

Mr. Khalili is a 49 -year old tour guide. He showed us old photographs of the marshlands which were homes to migrating flamingos. Running his hands through his gray hair in disbelief, he said: ‘These pictures are from 20 years ago. Zayandeh-Rud was 30 meters wide in some places. A two-meter waterfall fed a protected habitat for birds, fishes, insects and various plants and animals. The wetland was a wildlife sanctuary. All that is left today is a narrow stream flowing with foul-smelling groundwater spilling out of artesian wells and canals.’

From time to time, a solitary bird stops by for a short visit. Meanwhile, the desertification of the land continues at a rapid pace. A brown and red sun-baked earth has replaced the wet blue and green marshland. The river banks continue to recede, and the remaining surface water is turning into a thick and stagnant pool of mud. ‘The crisis will reach its climax this year,’ Khalili says.

It would take years to revive the marshland, even if the water was to return today to the region. ‘This is a complex interdependent echo system that could completely fall apart if one of its links breaks,’ Khalili says.

‘Look. Look up there,’ Khalili shouts, pointing to a spot in the sky. Two flamingos are flying in the distance. He takes out his cell phone and records their flight. Tears of joy and excitement fill his eyes. After coming to the same spot for months, Khalili has finally been rewarded with the rare glimpse of two flamingos gliding effortlessly towards the warm orange glow of summer dusk that illuminates the distant horizon.”

[Translated from Persian by Fardine Hamidi]