By Ahmed Aboulenein

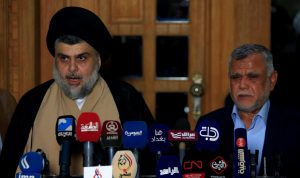

BAGHDAD, June 13 (Reuters) – Cleric Moqtada al-Sadr and Iranian-backed militia chief Hadi al-Amiri’s decision to choose compromise over confrontation and strike an alliance, aiming to form the next Iraqi government, has eased tensions after elections marred by fraud allegations.

Sadr’s bloc scored a stunning victory in the May 12 parliamentary election by tapping growing public discontent with neighbouring Iran’s sway in Iraq and promising to deliver what past governments have not: jobs, better services and stability.

But beneath the surface there were fears that regional power Tehran, which before the vote said it would never let Sadr govern, would sabotage the mercurial cleric and set the stage for a showdown that could turn bloody.

In the end, an alliance has emerged of strange bed-fellows: Sadr who portrays himself as a nationalist and Amiri, Iran’s most powerful ally in Iraq whose grouping came second. Their choice of pragmatism has lowered the risk of violence among Iraq’s Shi’ite majority after a costly conflict war with the Sunni Muslim militants of Islamic State.

Sadr is treading cautiously, aware that Iran has manipulated Iraqi politics in its favour in the past and of Tehran’s vast sway in its most important Arab ally.

In a 2010 election, Vice President Ayad Allawi’s bloc won the most seats but he was prevented from becoming prime minister, blaming Iranian manoeuvring.

“If he (Sadr) insisted on fighting everyone at the same time he would be outmanoeuvred, and the pressure of a re-run of the elections was too much,” said a Western diplomat in Baghdad.

Tehran, which has thrived amid Iraqi Shi’ite rivalries in the past by acting as a broker, has its own motivations.

Sadr’s alliance with Amiri, announced in the holy Shi’ite city of Najaf to project a sense of unity, gives Tehran more leverage over the formation of Iraq’s next government.

FEELING THE HEAT

Amiri, who spent two decades fighting Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein from Iran and speaks Farsi fluently, is one of the most powerful figures in Iraq.

His Badr Organisation controls the interior ministry and he played a decisive role in the battle against Islamic State.

“Amiri had the momentum behind him especially in this election, this is an opportunity for him,” said Hassan Hassan, senior fellow at the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy. “He is fresh off the field, very popular in some circles.”

Amiri is close to Major General Qassem Soleimani, commander of foreign operations for Iran’s Revolutionary Guards who has great influence in Iraq.

Soleimani was in Iraq this week, a second Western diplomat in Baghdad said, adding that it is likely that he advised Amiri to ally with Sadr, who recently met Iran’s ambassador.

The Iranians have decided they must accept Sadr, the diplomat said, and he will have in turn realised he must work with Amiri to safeguard his victory.

Shunning Amiri could make life difficult for Sadr. His foe, former Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki, is still in the picture despite being forced out of office and widely blamed for Islamic State’s seizure of a third of Iraq.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/download-4.jpeg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” caption=”A campaign poster of former Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki is seen in the street ahead of the parliamentary election, in Baghdad, Iraq, May 1, 2018. Picture taken May 1, 2018. REUTERS/Thaier al-Sudan” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

In 2008, Maliki ordered a crackdown on forces loyal to Sadr in the Shi’ite heartland.

According to the first diplomat who recently met Sadr, he felt pressured and feared his victory was going to vanish.

Acting on what Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi said were widespread violations, a parliament stacked with lawmakers who failed to retain their seats mandated a nationwide recount.

Some politicians said the election should be repeated.

MIDDLE GROUND

Abadi seemed to lose the most out of the alliance, diplomats and analysts said. Even though he has balanced the interests of Iran and the United States, who compete for influence in Iraq, his bloc has yet to join any coalition.

He may yet win a second term as a compromise candidate, albeit as a much weaker premier, beholden to Sadr and Amiri.

Iran does not seem worried about the uncertainty but is under growing pressure to preserve its interests in the Middle East especially in Iraq.

U.S. President Donald Trump pulled out of a nuclear deal with Tehran then engaged nuclear state North Korea, increasing Tehran’s isolation.

In Yemen, Houthi forces aligned with Iran face the biggest offensive from a Saudi-led coalition in the three-year conflict, part of a regional proxy war between Riyadh and Tehran.

“There is a certain element of pragmatism in Iran on foreign policy,” said Renad Mansour, research fellow at Chatham House in London. “Iran does not want Iraq to collapse but it also does not want Iraq to be too strong. They want a middle ground.”

Even if Sadr’s deal with Amiri succeeds, he may have to contend with grievances from members of his own bloc who insist Tehran would not be allowed to interfere in Iraqi affairs.

(Reporting by Ahmed Aboulenein; additional reporting and editing by Michael Georgy)